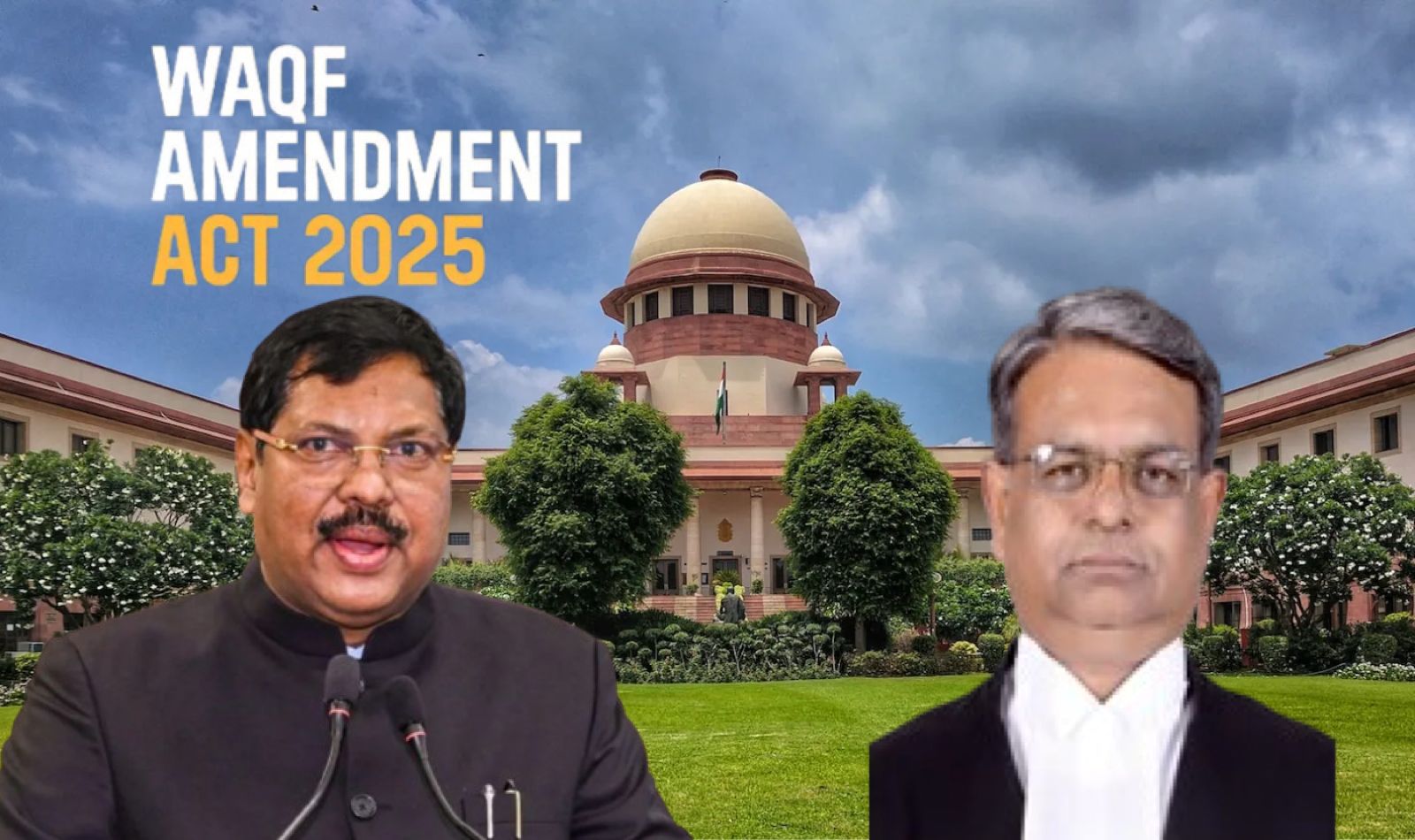

SC stays certain provisions of Waqf Amendment Act 2025: Is judiciary becoming a shield for encroachment?

The Supreme Court of India has once again stepped into a zone where it was never meant to tread: legislating from the bench. On September 14, the apex court stayed key provisions of the Waqf (Amendment) Act, 2025, which had been passed by Parliament earlier this year after an intensive debate for over 12-hours in the Lok Sabha and a subsequent 14-hour discussion in the Rajya Sabha. What the Supreme Court said Chief Justice BR Gavai, while pronouncing the order, remarked that “only in the rarest of rare cases a legislation can be stayed.” Yet, ironically, the bench went on to do precisely that. The Court observed that though the 5-year condition for a Muslim practitioner before creating waqf was not arbitrary in itself, in the absence of a mechanism to verify such practice, it could lead to misuse. Hence, the provision was stayed till state governments frame rules. On the question of government land claimed as waqf property, the Court went further. It said that “permitting the Collector to determine the rights of the properties is against the doctrine of separation of powers as the Executive can’t be permitted to determine the rights of citizens.” In essence, it meant until a tribunal or a higher court decides the matter conclusively, the government cannot de-recognize such land from waqf claims. No third-party rights can be created either, but the encroacher, conveniently, continues to sit tight on disputed land. The Court also imposed caps on the number of non-Muslim members in Waqf Boards and directed that as far as possible, the CEO of a Board should be Muslim. It justified these as interim “protective” measures while the larger constitutional challenge is heard. This move raises an uncomfortable yet crucial question: Is the judiciary slowly becoming the biggest stumbling block in the government’s effort to reclaim illegally occupied lands and bring accountability to India’s largest landowner after the Indian Railways, the Waqf boards? Let’s be clear. The court did not strike down the entire law. It carefully picked provisions, citing arbitrariness and separation of powers. But in doing so, it created a dangerous precedent: a court can be used to stall executive action whenever vested interests feel threatened. For decades, the Waqf boards have operated as a parallel land authority, often beyond the pale of scrutiny, claiming vast swathes of land, sometimes even government land, as “waqf property.” The 2025 amendments were a long-overdue attempt to bring order, transparency, and accountability. Yet, the judiciary’s intervention threatens to undo this effort. Why these observations are problematic The Court’s logic may sound legally sophisticated, but its practical effect is disastrous. Take the Collector’s role. In any land dispute, be it between private citizens, companies, or even between individuals and the State, the first level of determination always begins with the revenue officer. That is the system across India. Why should waqf properties suddenly enjoy an exemption from this? By ousting the executive from this process, the Court has made it nearly impossible for the government to protect its land from encroachment without first wading through years of litigation. As for the 5-year condition, the Court itself acknowledged that people could convert opportunistically to Islam just to misuse waqf protections. Yet, instead of allowing the law to operate, it suspended it until rules are framed. Essentially, the judiciary is saying: “Yes, the Parliament was right in principle, but we will not allow the law to run until we micromanage its rule-making.” This is nothing but judicial babysitting of the legislature. Government land as Waqf property? Court’s stay encourages encroachment One of the most significant provisions Parliament introduced was that if a property is in dispute with the government, it cannot be treated as Waqf property until the matter is resolved. This was a common-sense safeguard. After all, how can disputed government land suddenly be stamped as “Allah’s property” merely because a Waqf board unilaterally decides so? Yet, the Supreme Court stayed this provision. Its reasoning? That allowing a government officer like the Collector to decide such disputes violates the “separation of powers.” So until a tribunal or court finally settles the matter, a process that can drag on for decades, the Waqf board’s claim stands. In effect, the stay order arms encroachers with a legal shield to squat on government land indefinitely, knowing full well that litigation in India is a marathon. Imagine the motivation this gives to encroachers: Aggressively go hunting for lands, squat on them until challenged. If the local administration orders them to vacate, drag the case endlessly, and continue enjoying the fruits of encroachment while the government’s hands remain tied. This isn’t judicial protection of rights; it’s judicial endorsement and encourageme

The Supreme Court of India has once again stepped into a zone where it was never meant to tread: legislating from the bench. On September 14, the apex court stayed key provisions of the Waqf (Amendment) Act, 2025, which had been passed by Parliament earlier this year after an intensive debate for over 12-hours in the Lok Sabha and a subsequent 14-hour discussion in the Rajya Sabha.

What the Supreme Court said

Chief Justice BR Gavai, while pronouncing the order, remarked that “only in the rarest of rare cases a legislation can be stayed.” Yet, ironically, the bench went on to do precisely that. The Court observed that though the 5-year condition for a Muslim practitioner before creating waqf was not arbitrary in itself, in the absence of a mechanism to verify such practice, it could lead to misuse. Hence, the provision was stayed till state governments frame rules.

On the question of government land claimed as waqf property, the Court went further. It said that “permitting the Collector to determine the rights of the properties is against the doctrine of separation of powers as the Executive can’t be permitted to determine the rights of citizens.” In essence, it meant until a tribunal or a higher court decides the matter conclusively, the government cannot de-recognize such land from waqf claims. No third-party rights can be created either, but the encroacher, conveniently, continues to sit tight on disputed land.

The Court also imposed caps on the number of non-Muslim members in Waqf Boards and directed that as far as possible, the CEO of a Board should be Muslim. It justified these as interim “protective” measures while the larger constitutional challenge is heard.

This move raises an uncomfortable yet crucial question: Is the judiciary slowly becoming the biggest stumbling block in the government’s effort to reclaim illegally occupied lands and bring accountability to India’s largest landowner after the Indian Railways, the Waqf boards?

Let’s be clear. The court did not strike down the entire law. It carefully picked provisions, citing arbitrariness and separation of powers. But in doing so, it created a dangerous precedent: a court can be used to stall executive action whenever vested interests feel threatened.

For decades, the Waqf boards have operated as a parallel land authority, often beyond the pale of scrutiny, claiming vast swathes of land, sometimes even government land, as “waqf property.” The 2025 amendments were a long-overdue attempt to bring order, transparency, and accountability. Yet, the judiciary’s intervention threatens to undo this effort.

Why these observations are problematic

The Court’s logic may sound legally sophisticated, but its practical effect is disastrous. Take the Collector’s role. In any land dispute, be it between private citizens, companies, or even between individuals and the State, the first level of determination always begins with the revenue officer. That is the system across India. Why should waqf properties suddenly enjoy an exemption from this? By ousting the executive from this process, the Court has made it nearly impossible for the government to protect its land from encroachment without first wading through years of litigation.

As for the 5-year condition, the Court itself acknowledged that people could convert opportunistically to Islam just to misuse waqf protections. Yet, instead of allowing the law to operate, it suspended it until rules are framed.

Essentially, the judiciary is saying: “Yes, the Parliament was right in principle, but we will not allow the law to run until we micromanage its rule-making.” This is nothing but judicial babysitting of the legislature.

Government land as Waqf property? Court’s stay encourages encroachment

One of the most significant provisions Parliament introduced was that if a property is in dispute with the government, it cannot be treated as Waqf property until the matter is resolved. This was a common-sense safeguard. After all, how can disputed government land suddenly be stamped as “Allah’s property” merely because a Waqf board unilaterally decides so?

Yet, the Supreme Court stayed this provision. Its reasoning? That allowing a government officer like the Collector to decide such disputes violates the “separation of powers.” So until a tribunal or court finally settles the matter, a process that can drag on for decades, the Waqf board’s claim stands. In effect, the stay order arms encroachers with a legal shield to squat on government land indefinitely, knowing full well that litigation in India is a marathon.

Imagine the motivation this gives to encroachers: Aggressively go hunting for lands, squat on them until challenged. If the local administration orders them to vacate, drag the case endlessly, and continue enjoying the fruits of encroachment while the government’s hands remain tied. This isn’t judicial protection of rights; it’s judicial endorsement and encouragement of encroachment.

Parliament passes, judiciary pauses

The larger issue here is not about the fine print of waqf reforms but about constitutional propriety. Parliament debated and passed the Amendment Act. The executive brought it into effect, citing the urgent need to curb the misuse of waqf claims. Yet, the judiciary has stepped in, not to strike down a law after a full hearing, but to “temporarily” suspend parts of it. In practice, the judiciary has assumed legislative and executive powers.

This pattern is not new. Whether it was farm laws, CAA implementation, or now waqf amendments, courts have increasingly taken upon themselves the role of not just interpreting the law but deciding whether a law can be operational at all. This is judicial overreach, plain and simple. And it undermines the delicate balance between the three pillars of democracy.

When courts begin to “pause” laws passed by the elected representatives of the people, they effectively place themselves above Parliament. Is this the constitutional design? Certainly not.

Selective sensitivity

Interestingly, the same courts that routinely preach judicial restraint suddenly become hyperactive when it comes to laws affecting “minority sentiments.” The Waqf boards today control more land than many state governments, yet their opacity has remained unquestioned for decades. The 2025 amendments aimed to abolish dubious practices like “waqf by user,” prevent creation of waqfs over protected monuments and Scheduled Areas, and subject them to the Limitation Act like everyone else.

Most of these provisions were left untouched. Yet, the moment the government asserted its right to prevent its own land from being swallowed into the waqf blackhole, the judiciary chose to intervene. Why this selective sensitivity? Why should public land, the collective property of taxpayers, be treated as second-class compared to claims of a religious body?

Dangerous precedent

The Supreme Court has often reminded the executive and legislature of the “rarest of rare” standard in staying laws. Ironically, it seems to forget its own principle when it comes to waqf. If every contested provision of a statute can be stayed merely because petitioners dislike it, then Parliament’s authority stands hollow. Tomorrow, every reform, from UCC to temple management laws, will be dragged to the courts, not for final adjudication, but to ensure endless paralysis.

This is the real danger of the September 14 order. It signals to vested interest groups: If you cannot stop a law in Parliament, stop it in the courts.

The Modi government has a daunting task: reclaiming India’s land from illegal encroachment and parallel legal systems. The Waqf (Amendment) Act 2025 was a bold step in this direction. By staying critical of provisions, the Supreme Court has not only emboldened encroachers but also sent a chilling message to Parliament: your mandate is conditional upon our approval.

At stake is not just waqf land but the very principle of the separation of powers. If courts continue to act as the ultimate arbiter of legislative wisdom, India risks turning into a “juristocracy” where unelected judges dictate governance. That is not what our Constitution envisioned.

The people of India elect Parliament to make laws. The courts’ job is to interpret, not interfere. The sooner the judiciary remembers this, the better it will be for our democracy.