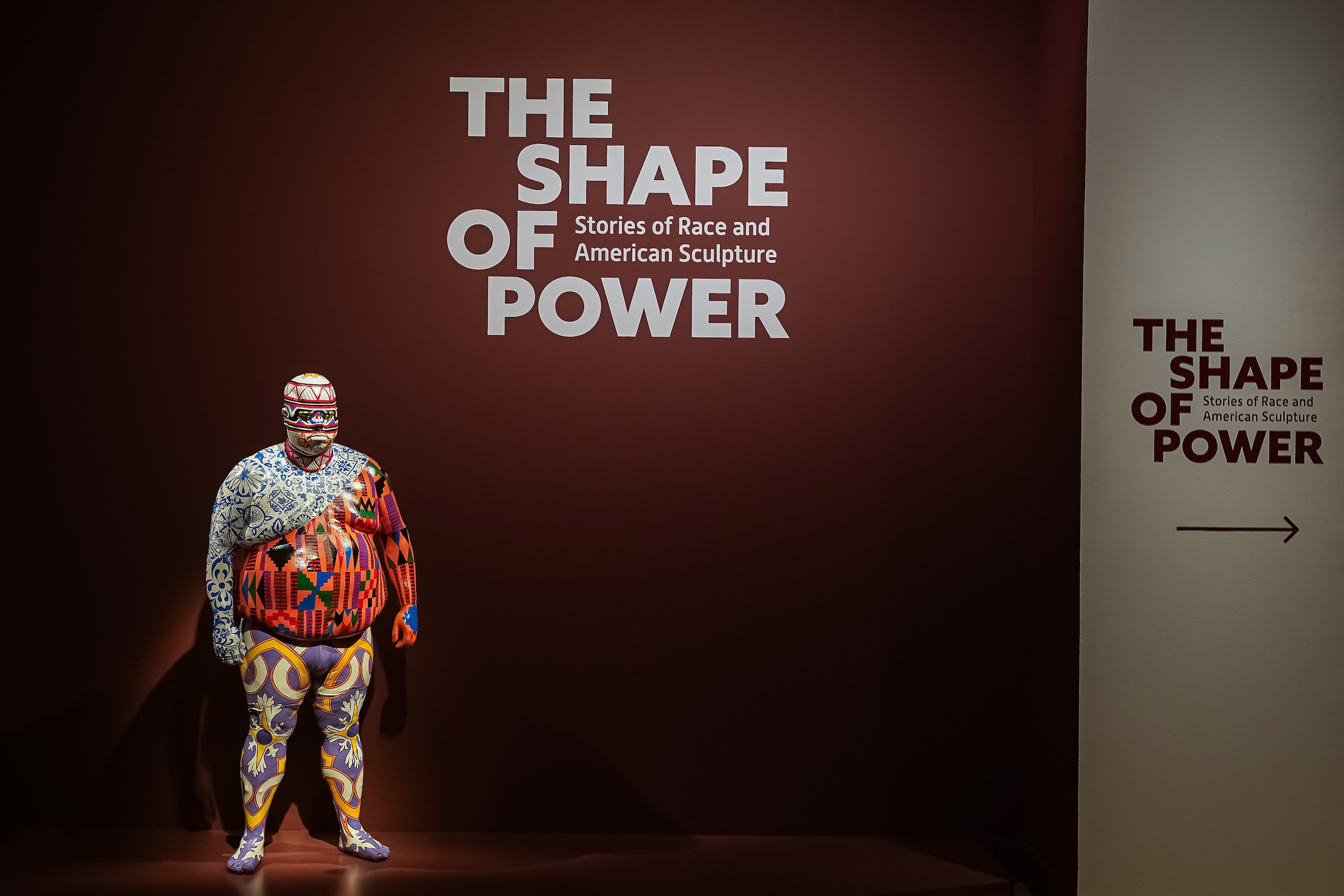

Canada: Ontario Court rejects asylum claim of ‘Khalistani’ Pardeep Singh – Read how refugee protections are repeatedly abused using the ‘Khalistan card’

On 6th September, the Federal Court in Toronto, Ontario rejected the asylum claim of one Pardeep Singh, an Indian citizen who had sought refuge in Canada after his work permit expired in November 2024. According to snippets of court documents shared by a freelance journalist who goes by the handle OnTheNewsBeat on social media platform X, Pardeep Singh entered Canada in February 2023 on a spousal work permit. Another fraud asylum seeker Pardeep Singh claims persecution on account of becoming radicalized as a Khalistani while in Canada Lost his appeal and was scheduled to be deported on September 8th Are the agencies monitoring these radicalized Canada returnees? pic.twitter.com/u1mOKiKEuK— Journalist V (@OnTheNewsBeat) September 14, 2025 He attempted to stay on by filing a refugee claim. However, his application was dismissed as ineligible under the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act. Notably, he had previously made a refugee claim in Australia between 2014 and 2019. Interestingly, Singh played the infamous ‘Khalistan card’ and claimed possibility of persecution by Indian authorities if he returned to his home country. The timeline of his case underlines a well-established pattern. After his work permit expired, Singh did not apply for an extension. Instead, he played the ‘Khalistan card’ and filed a refugee claim on 16th November 2024. This was rejected on grounds of prior asylum attempts. In February 2025, he was informed that he could apply for a Pre-Removal Risk Assessment (PRRA). For those who are unaware, PRRA is a process in Canada that allows certain individuals facing deportation to ask for protection if they believe they would be at risk if sent back to their home country. Through this option, applicants can present new evidence showing they face danger of persecution, torture, risk to life, or cruel and unusual treatment or punishment. The application is then reviewed by immigration officials before the removal. This option cannot be seen as a full asylum process but a last chance safeguard for people about to be deported, which in this case was Pardeep Singh. After getting information that he was eligible for PRRA, Singh pursued the option only to get his application rejected on 15th August 2025. Ten days later, the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) informed him that he would be deported on 8th September 2025. Singh challenged the decision with an Application for Leave and Judicial Review (ALJR) and sought a deferral of removal. However, his request was denied on 2nd September 2025. In the judgment, the Federal Court noted that Singh had submitted affidavits and evidence. However, the decision officer placed little weight on those documents. Instead, social media evidence presented by authorities highlighted Singh’s involvement in the Farmers’ Protest in India and his continued support for the Khalistan movement in Canada. The court specifically observed that Singh’s parents had also provided a joint affidavit in support of his claim. However, the officer found it lacking in substance, noting that it contained no concrete details about the alleged threats or harassment they faced and offered little clarity on the circumstances of their arrests. As a result, the affidavit was given minimal weight, with the focus instead shifting to Singh’s own online activities and public associations. A familiar modus operandi The rejection of Singh’s claim brought back a now-familiar tactic. The asylum route has become a convenient alternative for many Punjabi youth who are unable to migrate legally under skilled categories. In doing so, they invoke the infamous ‘Khalistan card’. The strategy works in one of two ways. Some adopt an outward persona of being pro-Khalistan to strengthen their claim of possible persecution in India, while others are genuine sympathisers of the Khalistani separatist ideology and attempt to parlay that into asylum. The logic is simple. They project themselves as victims of political and religious persecution linked to the Khalistan movement. These individuals expect sympathetic treatment in Western countries that often present themselves as protectors of minorities. While many attempts succeed, like in the case of now-dead Khalistani terrorist Hardeep Singh Nijjar, Singh’s case shows that not every attempt is successful. Repeated claims in multiple countries, lack of supporting evidence, or exposure of social media activity that confirms more opportunism than persecution can easily undermine the narrative. The ‘Khalistan card’ and its enablers The abuse of asylum procedures is not a new phenomenon. In Punjab, there is a cottage industry running around asylum claims. Local agents routinely guide youths on how to build a persecution story including vocabulary to use, organisations abroad to contact and affidavits to support their claim. Lawyers in Canada, the US, Australia, and the UK then take over. They often charge hefty fees to structure

On 6th September, the Federal Court in Toronto, Ontario rejected the asylum claim of one Pardeep Singh, an Indian citizen who had sought refuge in Canada after his work permit expired in November 2024. According to snippets of court documents shared by a freelance journalist who goes by the handle OnTheNewsBeat on social media platform X, Pardeep Singh entered Canada in February 2023 on a spousal work permit.

Another fraud asylum seeker Pardeep Singh claims persecution on account of becoming radicalized as a Khalistani while in Canada

— Journalist V (@OnTheNewsBeat) September 14, 2025

Lost his appeal and was scheduled to be deported on September 8th

Are the agencies monitoring these radicalized Canada returnees? pic.twitter.com/u1mOKiKEuK

He attempted to stay on by filing a refugee claim. However, his application was dismissed as ineligible under the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act. Notably, he had previously made a refugee claim in Australia between 2014 and 2019. Interestingly, Singh played the infamous ‘Khalistan card’ and claimed possibility of persecution by Indian authorities if he returned to his home country.

The timeline of his case underlines a well-established pattern. After his work permit expired, Singh did not apply for an extension. Instead, he played the ‘Khalistan card’ and filed a refugee claim on 16th November 2024. This was rejected on grounds of prior asylum attempts. In February 2025, he was informed that he could apply for a Pre-Removal Risk Assessment (PRRA).

For those who are unaware, PRRA is a process in Canada that allows certain individuals facing deportation to ask for protection if they believe they would be at risk if sent back to their home country. Through this option, applicants can present new evidence showing they face danger of persecution, torture, risk to life, or cruel and unusual treatment or punishment. The application is then reviewed by immigration officials before the removal. This option cannot be seen as a full asylum process but a last chance safeguard for people about to be deported, which in this case was Pardeep Singh.

After getting information that he was eligible for PRRA, Singh pursued the option only to get his application rejected on 15th August 2025. Ten days later, the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) informed him that he would be deported on 8th September 2025. Singh challenged the decision with an Application for Leave and Judicial Review (ALJR) and sought a deferral of removal. However, his request was denied on 2nd September 2025.

In the judgment, the Federal Court noted that Singh had submitted affidavits and evidence. However, the decision officer placed little weight on those documents. Instead, social media evidence presented by authorities highlighted Singh’s involvement in the Farmers’ Protest in India and his continued support for the Khalistan movement in Canada.

The court specifically observed that Singh’s parents had also provided a joint affidavit in support of his claim. However, the officer found it lacking in substance, noting that it contained no concrete details about the alleged threats or harassment they faced and offered little clarity on the circumstances of their arrests. As a result, the affidavit was given minimal weight, with the focus instead shifting to Singh’s own online activities and public associations.

A familiar modus operandi

The rejection of Singh’s claim brought back a now-familiar tactic. The asylum route has become a convenient alternative for many Punjabi youth who are unable to migrate legally under skilled categories. In doing so, they invoke the infamous ‘Khalistan card’. The strategy works in one of two ways. Some adopt an outward persona of being pro-Khalistan to strengthen their claim of possible persecution in India, while others are genuine sympathisers of the Khalistani separatist ideology and attempt to parlay that into asylum.

The logic is simple. They project themselves as victims of political and religious persecution linked to the Khalistan movement. These individuals expect sympathetic treatment in Western countries that often present themselves as protectors of minorities. While many attempts succeed, like in the case of now-dead Khalistani terrorist Hardeep Singh Nijjar, Singh’s case shows that not every attempt is successful. Repeated claims in multiple countries, lack of supporting evidence, or exposure of social media activity that confirms more opportunism than persecution can easily undermine the narrative.

The ‘Khalistan card’ and its enablers

The abuse of asylum procedures is not a new phenomenon. In Punjab, there is a cottage industry running around asylum claims. Local agents routinely guide youths on how to build a persecution story including vocabulary to use, organisations abroad to contact and affidavits to support their claim. Lawyers in Canada, the US, Australia, and the UK then take over. They often charge hefty fees to structure these asylum petitions.

This is a two-way problem. On one hand, fraudulent claims are being made to bypass the legal route of staying in a foreign country. On the other hand, actual supporters of the Khalistan movement, most of whom are either proclaimed terrorists or terror-sympathisers, find their way to countries like Canada away from Indian law enforcement agencies. Interestingly, despite having a treaty on the extradition of criminals, Canada has repeatedly rejected India’s requests, especially when it comes to Khalistan supporters.

Social media is filled with youth in Canada, the US, and Australia who openly glorify Khalistani terrorists, promote separatist propaganda, and amplify the rhetoric of groups like Sikhs for Justice (SFJ), a banned terrorist organisation in India. Host countries often provide a shield to these elements despite the security risk to themselves.

The dangers of asylum abuse

In principle, asylum is meant to protect individuals who face genuine threats of persecution, torture, or death in their home countries. It is a humanitarian instrument rooted in international law. However, the system begins to crumble when it is routinely gamed.

Fraudulent claims often clog asylum systems, delaying protection for those who genuinely need it. They also introduce security risks, especially when the asylum narrative is built around extremist ideologies. Canada, for instance, is facing the side-effects of supporting the Khalistani movement. It has ruined diplomatic relations with a friendly country, India. Host societies are left grappling with the unintended consequences, that too on an international level.

Lessons from past patterns

Canada has faced challenges with countless Punjabis seeking asylum over the years claiming possibility of persecution for supposed Khalistan sympathies. In many cases, they succeed. Former Sangrur MP Simranjit Singh Mann even boasted of issuing thousands of letters supporting asylum claims, often in exchange for money. These letters painted applicants as potential victims of state oppression, creating a paper trail to bolster their narratives.

Singh’s case as a cautionary tale

Pardeep Singh’s case is not extraordinary. It follows a predictable script. Arrival on a temporary permit, expiration of legal status, shift to asylum claim, invocation of the Khalistan card and eventual rejection. However, that does not mean the Federal Court has rejected the narrative. In some instances, claims survive because of technical grounds.

For example, Gurcharan Singh (IMM-12706-24), where the matter was remitted for redetermination over oral hearing inconsistencies; Iqbal Singh Dhaliwal (IMM-11033-24), where the Court found a key CBSA dossier overlooked and sent the case back; or Amandeep Singh and Kanwaldeep Kaur (IMM-4214-24), where the Court upheld findings that their Khalistan-based sur place claim was disingenuous and dismissed it. These examples show the narrative remains alive, with outcomes shifting case by case. These decisions came in the past two months in Toronto Federal Court.

In the case of Pardeep Singh, the Canadian authorities underlined his previous asylum claim in Australia and demonstrated that this was not an isolated attempt but part of a pattern. For Singh, the outcome is deportation and his case can very well be used by pro-Khalistani elements to put pressure on policymakers to amend rules that reflect the host country prioritising asylum seekers’ rights.

Conclusion

Pardeep Singh’s failed asylum claim is more than an individual story. As mentioned above, there were three decisions made in just two months on similar grounds. It is a reflection of how the ‘Khalistan card’ has become both a tactic and a liability in global migration politics. By attempting asylum in multiple countries, by leaning on separatist narratives, and by projecting a persona of persecution, such individuals represent a pattern that has become all too familiar.

The tragedy is, while these elements are playing with the system, genuine asylum seekers, those who are facing real threats, find their voices drowned out.