Who Was Chef Marie-Antoine Carême, the Subject of a (Sexy!) New Apple TV+ Series?

From the four “mother sauces” to croquembouche and mille-feuille, Carême’s undeniable legacy endures

This story was originally published as part of a historical Eater series called A Name You Should Know. It’s been updated timed to the release of Apple TV+’s Carême, a fictionalized take on the life of Marie-Antoine Carême, the man many consider to be the first celebrity chef.

It is difficult to overstate the importance, in modern Western cuisine, of Marie-Antoine Carême. Best known today for the spectacular sugar, marzipan, and pastry sculptures he designed and built called pièces montées — which still exist in fine dining, but are now more commonly made of chocolate — Carême’s real legacy came out of his systemization, rationalization, and professionalization of French cuisine in the early 1800s.

French cuisine remains one of history’s best documented, and though names like Escoffier, Soyer, Point, Vergé, and Bocuse are thrown around (and are indeed important in their own right), Carême was haute cuisine’s original maestro. He was the first to distinguish this rich, meat-heavy, decorative, more labor-intensive cuisine from regional French home cooking, and the first to catalogue and organize it so it could be easily understood by future generations. From a relative disarray of recipes and techniques, he extrapolated four essential sauces, known as “mother sauces,” which formed the basis of and garnish for hundreds of dishes. Over a century later, Auguste Escoffier would update and revise this system, but Carême gave Escoffier something to build upon.

“When we talk about the systems of French cuisine, it goes back to Carême,” says Priscilla Ferguson, professor of sociology and cuisinology at Columbia University. Carême’s work is a key reason why French cooking has permeated nearly every country across the globe, and remains the dominant cuisine in fine dining today.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/6590001/careme-portrait.0.jpg) Photo by Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images

Photo by Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images

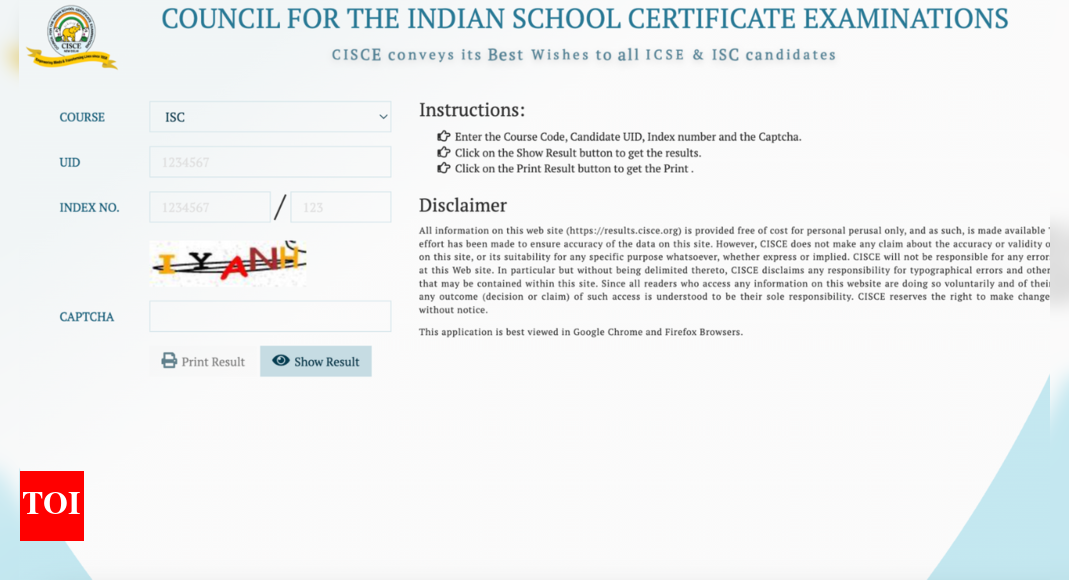

Born in Paris on June 8, 1784, Carême died just 49 years later in 1833, having spent nearly 40 years of his life working in professional kitchens. Accounts vary widely, but most sources agree Carême was born to a large, poor family in Paris. By the age of 10 he was out on his own, and Carême signed on for a six-year internship at a small tavern on the edge of Paris called the Fricassée de Lapin; he started as a dishwasher and gopher, or runner. In those days, taverns were hubs for city life and often operated as inns for travelers passing through town. They always served alcohol, and occasionally served food as well.

At 16, Carême was onto his next job, this time at a noteworthy pâtisserie near the Palais-Royal owned by Sylvain Bailly, a famous pâtissier at the time. Unlike taverns, which were casual and served the working classes, pâtisseries served the wealthy. It was at Bailly’s shop that Carême blossomed. Bailly recognized the young boy’s talent and encouraged him to get a more formal education. During this time Carême learned to read and write and took a keen interest in architecture. He would spend days studying in the library and then return to the shop to reproduce classic architectural forms in sugar and pastry. Bailly, seeing a possible market for these creations, set them out as decorative displays and eventually sold them as banquet centerpieces.

Within two years, members of France’s ruling class began to notice the young apprentice’s work and contracted him for special-occasion pieces outside the pastry shop. According to some sources, around the turn of the century Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord (Talleyrand), Napoleon’s chief diplomat at the time, hired Carême to work under his personal chef. About a decade later, when Napoleon installed Talleyrand at the Château de Valençay — a residence purchased for the sole purpose of entertaining diplomatic guests from abroad — Carême came along. Some sources say Carême owned his own Paris pastry shop while working freelance for Tallyrand. Regardless, it was under Talleyrand’s chef that Carême learned the savory side of the kitchen.

In 1815, Carême left Paris to work in London as head chef for George, Prince of Wales. He left the country just three years later, but while in England, he wrote his first book, Le pâtissier royal, a 482-page manual and treatise split into two volumes comprising sweet and savory recipes, complete with rough line drawings for the more elaborate dishes. In Le pâtissier royal, the first of what would be many books, Carême wrote of pastry’s architectural nature. By 1881, when the novelist Anatole France published his first book, The Crime of Sylvestre Bonnard, Carême would be quoted as saying, “The fine arts are five in number, to wit: painting, sculpture, poetry, music, architecture — whose main branch is confectionery.”

For some scholars, it is difficult to separate Carême’s talent from his vainglorious self-promotion. “He printed his portrait in his books, so everyone knew what he looked like,” says Ken Albala, professor of history and director of food studies at University of the Pacific. “And he referred to himself in a grand manner, as the ‘chef of kings and king of chefs.’”

Carême may or may not have been the first to pipe meringue through a pastry bag; to perfect the cream puff; to melt and mold sugar like glass, but his methods were the first to be well-documented. He’s credited with being the first cookbook author to use the phrase, “you can try this for yourself at home.” In addition to one-of-a-kind, fanciful cakes, layered jellies, and molded or carved structures, he invented desserts like strawberries Romanov, coeur à la crème, croquembouche, mille-feuille, and charlotte Russe. Carême’s playfulness and outside-the-box thinking lives on in modern molecular gastronomy; his precision and pageantry informs modern American fine dining.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25976771/Careme_Photo_010210.jpg) Apple TV+

Apple TV+

Due to the book’s popularity, a second edition of Le pâtissier royal was printed just three months after its first run. Carême wrote several more books in his lifetime, including the seminal five-volume L’Art de la cuisine française au dix-neuvième siècle. Traité élémentaire et pratique., in which he posits that cream-based or otherwise thickened sauces are superior to thinner stocks, and lays out a complete catalogue of both sweet and savory French cuisine. It was in the book’s final volume where he notes, “I want order and taste. A well-displayed meal is enhanced one hundred percent in my eyes.”

In the early 19th century, when Carême’s books were being published, chefs learned by apprenticeship, mimicking techniques they saw others develop. It was a process of watching, learning, and repeating. Recipes existed, but were not organized (formal culinary schools would not appear in France until late in the century). There was no comprehensive effort to categorize what was then a very quickly evolving cuisine, specific to high society and France’s ruling class, which involved hundreds of new techniques, expensive ingredients, and teams of chefs to execute. Rich in butter and cream, luxurious, decorative, and extremely fussy, this cooking style is called grand cuisine francaise or haute cuisine, and it continues to influence cooking across the globe. Were it not for Carême, however, it may never have been documented as precisely or as extensively.

“His most lasting change is that he systematized cuisine,” Ferguson says. “He starts his last book with how you make bouillon, and then that bouillon is a basis for several different kinds of soup; separately, it is a basis for his sauces. Then, like Legos, you start with one recipe and build upon it, and build upon that.” Eventually you have a complete dish, a full banquet, a massive slew of foods of all temperatures, textures, and utilizing a range of techniques. “It’s that rationalization,” Ferguson says, “that set him apart from his contemporaries.” Carême similarly systemized dress as a way to professionalize the culinary arts: Just as doctors and lawyers were expected to dress in a certain way, Carême felt that chefs should wear uniforms. He donned a double-breasted jacket as a uniform, and popularized a version of the chef’s toque.

It was in his series of manuals that Carême created the concept of the four mother sauces, recipes that represent a distillation of the elemental building blocks of French cuisine. Though he is credited with establishing these sauces, he was not known for them in his day. It would take another century and another chef — Escoffier — before the systemization of French haute cuisine would be complete, and before Carême’s work on the savory side of the kitchen would be appreciated by future generations.

But according to Albala, Carême was most certainly the first celebrity chef. “In many ways Carême was born at just the right time,” Albala says. “France is flourishing and the printing press makes it possible for his books to be mass produced. They were not expensive at all. They were full of his drawings, architectural drawings that people liked to gawk at. It was like a coffee table book today, because for the most part people could not reproduce these things at home.” The books were quickly translated into English and spread throughout northern Europe, and many are still in print. “Very few chefs before him are well-known,” Albala says, “which is not to say royal chefs before him hadn’t written cookbooks. But these books didn’t have enormous print runs, nor did they become best-sellers.”

In subsequent years Carême would go on to work for Russian Emperor Alexander 1,

Russian Princess Catherine Bagration (while she lived in France), and several other lords, princes, and ambassadors from across Europe before his final stint in the kitchens of Baron James de Rothschild.

Some sources say he retired from work in 1829, at the age of 45, to focus on writing. Others say he died while on the job. “Poor guy, died rather young,” says Paul Freedman, Chester D. Tripp professor of history at Yale and author of Food: The History of Taste. “The techniques of cooking at that time required coal, so he died of some kind of pulmonary disease in his forties.” Even chefs who cooked for royalty were relegated to the basement and frequently suffered after years of breathing smoke from the stoves and ovens. Carême nevertheless sought to inspire young chefs who pursued the culinary arts: “Young people who love your art; have courage, perseverance... always hope... don’t count on anyone, be sure of yourself, of your talent and your probity and all will be well,” he wrote in L'Art de la cuisine française.

But ultimately, Carême’s view of cuisine was limited to that of the ruling class. He didn’t write or categorize cuisine for commerce, and his style was limited to using the best of the best, to having no constraints — financial or material. After his formal apprenticeship, he spent no time in restaurants or bakeries. “Carême had a vision of a stable society,” says Ferguson, “while Escoffier writes in the preface to his guide on French cooking that society is changing all the time.” Carême didn’t like the individualization of cuisine, the 19th-century way of serving menus course by course (the service style, which from Russia, is still referred to as service à la russe). “What he liked,” Ferguson says, “was a fantastical display, or service à la française. Everyone sat around a table and it was laid out with all manner of food, presented on grand platters, towering structures of cold salads, soups, hot roasts, stews, delicate pastries, rich sauces. The diner was not given a menu, the chef dictated the menu.”

In this way, Carême left room for Escoffier to see the bigger picture: How a categorization of cuisine could extend to the organization of a kitchen brigade, the training of chefs, the monetization and modernization of restaurants, and adaptation to an-ever changing diner with ever-changing demands. Despite this, Carême understood what many writers and bon vivants since have come to appreciate: To live well, one must dine well. “When we no longer have good cooking in the world,” Carême wrote in the first few pages of Le Cuisinier parisien, “we will have no literature, nor high and sharp intelligence, nor friendly gatherings, nor social harmony.”