A generational reset with roots: Why the rise of Nitin Nabin marks a quiet BJP–RSS reconciliation

The Bharatiya Janata Party’s decision to appoint 45-year-old Nitin Nabin as its national working president on December 14, 2025, is far more than a routine organisational reshuffle. It is a landmark moment that encapsulates a delicate yet profound renewal in the BJP’s evolving relationship with its ideological mentor, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). At a time when Indian politics is marked by coalition compulsions, generational churn, and ideological contestation, Nabin’s elevation signals a strategic pause and reset rooted in continuity rather than confrontation. There is symbolism in abundance. Born in 1980, the same year the BJP itself was founded, Nitin Nabin represents a political generation that has grown alongside the party’s ideological maturation. At an age when many leaders are still negotiating state-level relevance, Nabin arrives at the national stage with a rare blend of youth, administrative credibility, organisational depth, and ideological grounding. Crucially, he does so without having been “Delhi-fied” a distinction that the RSS has historically valued, and one that has often placed it at odds with the BJP’s central leadership. Nabin’s political journey began under tragic circumstances. Following the untimely death of his father, a respected BJP leader who twice won from Patna West during the politically hostile era of Lalu Prasad Yadav’s dominance, Nabin entered electoral politics in 2006 through a by-election. Critics initially dismissed his victory as a sympathy-driven mandate. Yet nearly two decades later, as a five-term MLA from Bankipur and Bihar’s Road Construction Minister, Nabin has decisively outgrown that label. His sustained connection with constituents, emphasis on accessibility, and focus on delivery over rhetoric have earned him cross-party respect. In Nitish Kumar’s often-fluid alliance governments, Nabin stood out as a dependable and non-controversial performer. His stewardship of Bihar’s road infrastructure aimed at shrinking travel time between Patna and remote districts to mere hours, mirrored Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s national infrastructure vision. Roads, after all, are not merely concrete; they are instruments of economic integration, social mobility, and state capacity. That even persistent critics such as Prashant Kishor refrained from targeting Nabin on corruption underscores his clean image in a political environment not known for generosity. Equally significant is Nabin’s organisational résumé. As head of the BJP’s youth wing in Bihar, and later as election in-charge in states like Chhattisgarh and Sikkim, he demonstrated an ability to mobilise cadres, manage internal dynamics, and convert ideological clarity into electoral outcomes. These experiences have shaped him into a rare hybrid: an administrator who understands organisation, and an organiser who respects governance. It is here that historical parallels emerge most notably with the 2009 elevation of Nitin Gadkari as BJP president. That move, driven by the RSS after consecutive electoral setbacks, was an explicit attempt to break the dominance of Delhi-centric leadership and inject the organisation with ideologically grounded, non-metropolitan energy. Gadkari, then an outsider to Lutyens’ Delhi, brought innovation: digital mobilisation, diaspora outreach, and structured think-tank engagement. Many of these are now staples of the BJP’s formidable electoral machinery. Yet Gadkari’s tenure was abruptly truncated amid allegations related to his private business ventures, controversies the RSS believed were amplified to sabotage its organisational reboot experiment. The subsequent reversion to familiar Delhi faces reinforced the perception that genuine decentralisation and generational renewal faced internal resistance. The post-2024 Lok Sabha scenario offered a similar moment of introspection. While the BJP retained power, it fell short of its more ambitious targets and entered a phase of coalition dependence. Ground-level feedback from cadres and Sangh functionaries alike pointed to the need for grooming younger leaders steeped in ideological ethos, capable of sustaining the movement beyond immediate electoral cycles. Nitin Nabin fits this blueprint almost perfectly. What distinguishes his appointment, however, is the absence of overt friction. Unlike 2009, this does not appear as an RSS imposition but as a consensual evolution within the Modi-Shah framework. For a leadership known for centralised control, accommodating Nabin reflects pragmatic adaptation. He is not an ideological novice being parachuted in, nor an organisational rebel. He has delivered within the existing strategic architecture, while also embodying the renewal many seek. The RSS, for its part, has long maintained the formal separation between itself and the BJP mentor versus political instrument. Yet it has always excelled at long-term planning, preferring subtle cultivation over public confrontation.

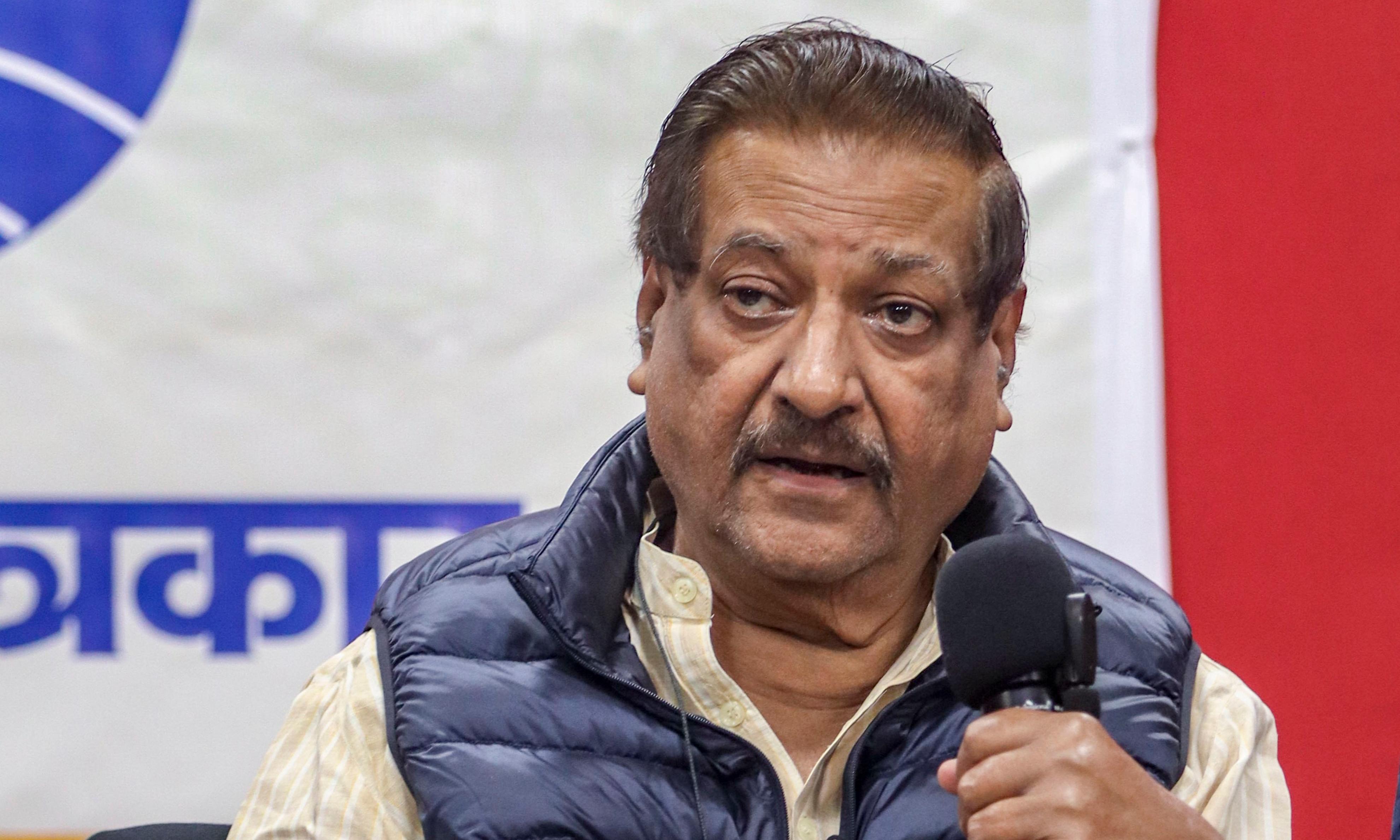

The Bharatiya Janata Party’s decision to appoint 45-year-old Nitin Nabin as its national working president on December 14, 2025, is far more than a routine organisational reshuffle. It is a landmark moment that encapsulates a delicate yet profound renewal in the BJP’s evolving relationship with its ideological mentor, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). At a time when Indian politics is marked by coalition compulsions, generational churn, and ideological contestation, Nabin’s elevation signals a strategic pause and reset rooted in continuity rather than confrontation.

There is symbolism in abundance. Born in 1980, the same year the BJP itself was founded, Nitin Nabin represents a political generation that has grown alongside the party’s ideological maturation. At an age when many leaders are still negotiating state-level relevance, Nabin arrives at the national stage with a rare blend of youth, administrative credibility, organisational depth, and ideological grounding. Crucially, he does so without having been “Delhi-fied” a distinction that the RSS has historically valued, and one that has often placed it at odds with the BJP’s central leadership.

Nabin’s political journey began under tragic circumstances. Following the untimely death of his father, a respected BJP leader who twice won from Patna West during the politically hostile era of Lalu Prasad Yadav’s dominance, Nabin entered electoral politics in 2006 through a by-election. Critics initially dismissed his victory as a sympathy-driven mandate. Yet nearly two decades later, as a five-term MLA from Bankipur and Bihar’s Road Construction Minister, Nabin has decisively outgrown that label. His sustained connection with constituents, emphasis on accessibility, and focus on delivery over rhetoric have earned him cross-party respect.

In Nitish Kumar’s often-fluid alliance governments, Nabin stood out as a dependable and non-controversial performer. His stewardship of Bihar’s road infrastructure aimed at shrinking travel time between Patna and remote districts to mere hours, mirrored Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s national infrastructure vision. Roads, after all, are not merely concrete; they are instruments of economic integration, social mobility, and state capacity. That even persistent critics such as Prashant Kishor refrained from targeting Nabin on corruption underscores his clean image in a political environment not known for generosity.

Equally significant is Nabin’s organisational résumé. As head of the BJP’s youth wing in Bihar, and later as election in-charge in states like Chhattisgarh and Sikkim, he demonstrated an ability to mobilise cadres, manage internal dynamics, and convert ideological clarity into electoral outcomes. These experiences have shaped him into a rare hybrid: an administrator who understands organisation, and an organiser who respects governance.

It is here that historical parallels emerge most notably with the 2009 elevation of Nitin Gadkari as BJP president. That move, driven by the RSS after consecutive electoral setbacks, was an explicit attempt to break the dominance of Delhi-centric leadership and inject the organisation with ideologically grounded, non-metropolitan energy. Gadkari, then an outsider to Lutyens’ Delhi, brought innovation: digital mobilisation, diaspora outreach, and structured think-tank engagement. Many of these are now staples of the BJP’s formidable electoral machinery.

Yet Gadkari’s tenure was abruptly truncated amid allegations related to his private business ventures, controversies the RSS believed were amplified to sabotage its organisational reboot experiment. The subsequent reversion to familiar Delhi faces reinforced the perception that genuine decentralisation and generational renewal faced internal resistance.

The post-2024 Lok Sabha scenario offered a similar moment of introspection. While the BJP retained power, it fell short of its more ambitious targets and entered a phase of coalition dependence. Ground-level feedback from cadres and Sangh functionaries alike pointed to the need for grooming younger leaders steeped in ideological ethos, capable of sustaining the movement beyond immediate electoral cycles. Nitin Nabin fits this blueprint almost perfectly.

What distinguishes his appointment, however, is the absence of overt friction. Unlike 2009, this does not appear as an RSS imposition but as a consensual evolution within the Modi-Shah framework. For a leadership known for centralised control, accommodating Nabin reflects pragmatic adaptation. He is not an ideological novice being parachuted in, nor an organisational rebel. He has delivered within the existing strategic architecture, while also embodying the renewal many seek.

The RSS, for its part, has long maintained the formal separation between itself and the BJP mentor versus political instrument. Yet it has always excelled at long-term planning, preferring subtle cultivation over public confrontation. By backing a leader unexposed to what many in Nagpur view as Delhi’s “foul political air,” the Sangh advances its vision quietly: “I will not impose, but develop through you.”

Shared long-term perspectives make this truce sustainable. Prime Minister Modi’s intense engagement with Bihar, evident in repeated visits and development commitments, aligns with RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat’s personal familiarity with the state, where he served as prant pracharak. Bhagwat likely observed Nabin’s early ideological grooming, lending the appointment an additional layer of trust and continuity.

Geography, too, matters. As the first BJP working president from eastern India, Nabin’s rise signals a deliberate eastward thrust. With Bihar as the anchor, the party aims to consolidate gains and push deeper into challenging regions such as West Bengal, Odisha, and the Northeast. The objective is clear: replicate the ideological and organisational hegemony achieved in western India by blending development narratives with cultural self-assertion. Nabin’s Kayastha background adds a layer of social nuance without overshadowing the broader Hindutva agenda.

Ultimately, Nitin Nabin’s ascent represents a mature phase in the BJP-RSS relationship, one that balances ideological steadfastness with electoral pragmatism. In an era defined by coalition arithmetic, ambitious visions like Viksit Bharat, and an increasingly competitive political landscape, this appointment strengthens the party’s organisational spine. By entrusting a young yet seasoned leader with the task of organisational surgery, cutting inefficiencies while reinforcing core strengths, the BJP signals its intent to think not just in terms of the next election, but the next few decades.

In that sense, this is not merely a promotion. It is a statement: resilience lies not in abandoning roots for realism, but in reconciling the two with confidence and clarity.