Why are ‘global human rights champions’ missing in action as Hindus are killed in Bangladesh? Where are the ‘Gretas’ & Trudeaus?

The attack on Khokon Chandra Das in Shariatpur and the lynching of Dipu Chandra Das were not chaotic flashes of mob rage driven by confusion or accident. In both cases, the chronology was horrifyingly apparent: a crowd gathered, restraint collapsed, and brutal force followed. Dipu Chandra Das was lynched by a mob, while Khokon Chandra Das was beaten, stabbed, doused with petrol, and set on fire, eventually dying in a hospital due to severe injuries. Pattern, not accident The brutal attack on Khokon Das and the killing of Dipu Chandra Das did not occur in isolation. In the last few weeks, multiple cases of mob violence targeting Hindus were reported across different districts in Bangladesh. In Rajbari, a Hindu man, Amrit Mondal, was attacked and killed after rumours were spread against him. In Mymensingh, Dipu Chandra Das was lynched by a mob acting on unverified blasphemy allegations. These are not isolated incidents. Hindus have been killed, lynched, stabbed, threatened and sometimes entire Hindu villages have been burned by Islamists in the past year and a half, with the caretaker government in Bangladesh always, always either pretending they are unrelated cases of petty crime, or trying to justify the cases as political anger against Awami League supporters. What links these cases is not a single allegation, but a recurring structure of violence. Mobs form rapidly, social restraint collapses, and violence is unleashed with extreme brutality. Homes are torched, families flee, and the wider Hindu community is left terrorised long after the crowd disperses. The aftermath follows another familiar script: sporadic arrests, official assurances, and then silence. Who spoke up and who didn’t The violence did draw responses, but unevenly. Governments moved first. India publicly conveyed concern over the safety of minorities in Bangladesh and urged Dhaka to ensure accountability. The United Kingdom also issued statements condemning the killings and emphasising the need to protect vulnerable communities. These were formal, on-record reactions that acknowledged the gravity of the crimes. Local activists from Bangladesh, Hindu organisations, and diaspora members were much more outspoken. To prevent the problem from falling out of the public eye, they planned protests, gave police updates, identified victims, and documented instances. What stood out was the relative quiet from major international human rights organisations, notably Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, unlike their response to conflicts such as Gaza, where both organisations issued rapid statements, detailed reports, emergency appeals, and sustained media briefings. The attacks against Hindus in Bangladesh did not trigger comparable mobilisation. The contrast is visible not only at the organisational level but also among high-profile global activists. Not a single prominent activist like Greta Thunberg, who has been outspoken and highly active on Gaza-related issues, even on political issues like the farmer protests in India, have not issued public statements on the recent killings of Hindus in Bangladesh. Public statements are still a big thing; she has not made a single tweet about these atrocities. The same silence applies to several other prominent international activists who regularly comment on human rights crises worldwide. There were no stand-alone investigations, no urgent global campaigns, and no continuous public briefings explicitly focused on these killings. Where Bangladesh was referenced, it was mainly within broader thematic discussions, not as a crisis demanding immediate international pressure. This comparison is difficult to overlook. When governments and local civil society speak clearly, but the world’s most influential human rights watchdogs respond cautiously or minimally, especially when they have demonstrated the capacity for rapid action elsewhere, it raises an uncomfortable but legitimate question. It is about priority and which victims are considered worthy of ongoing international campaigning. What silence actually Looks Like In this context, silence does not mean the complete absence of words. It is more subtle and more consequential. It appears as the absence of focused attention. There have been no dedicated investigative reports centred specifically on the plight of Hindu victims in Bangladesh. There have been no emergency action alerts urging supporters worldwide to pressure authorities. And there has been no sustained international media push driven by NGO briefings that keeps the issue in circulation beyond the first news cycle. This stands in contrast to how global human rights organisations have responded to other episodes of mob violence or communal attacks elsewhere. In those cases, even before court proceedings conclude, NGOs often publish preliminary assessments, appoint spokespeople, issue rolling updates, and frame the violence as a test of state responsibility. The

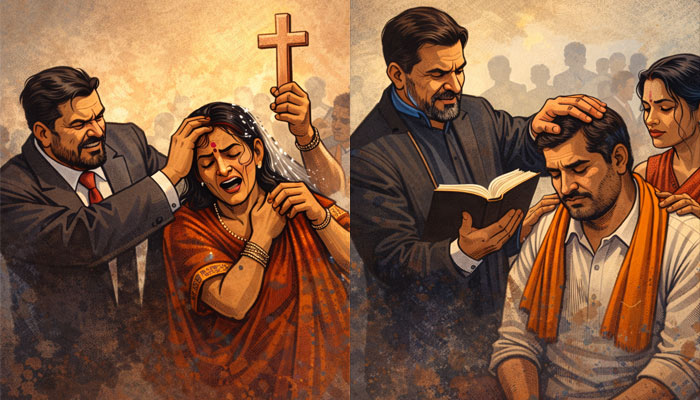

The attack on Khokon Chandra Das in Shariatpur and the lynching of Dipu Chandra Das were not chaotic flashes of mob rage driven by confusion or accident. In both cases, the chronology was horrifyingly apparent: a crowd gathered, restraint collapsed, and brutal force followed. Dipu Chandra Das was lynched by a mob, while Khokon Chandra Das was beaten, stabbed, doused with petrol, and set on fire, eventually dying in a hospital due to severe injuries.

Pattern, not accident

The brutal attack on Khokon Das and the killing of Dipu Chandra Das did not occur in isolation. In the last few weeks, multiple cases of mob violence targeting Hindus were reported across different districts in Bangladesh. In Rajbari, a Hindu man, Amrit Mondal, was attacked and killed after rumours were spread against him. In Mymensingh, Dipu Chandra Das was lynched by a mob acting on unverified blasphemy allegations.

These are not isolated incidents. Hindus have been killed, lynched, stabbed, threatened and sometimes entire Hindu villages have been burned by Islamists in the past year and a half, with the caretaker government in Bangladesh always, always either pretending they are unrelated cases of petty crime, or trying to justify the cases as political anger against Awami League supporters.

What links these cases is not a single allegation, but a recurring structure of violence. Mobs form rapidly, social restraint collapses, and violence is unleashed with extreme brutality. Homes are torched, families flee, and the wider Hindu community is left terrorised long after the crowd disperses. The aftermath follows another familiar script: sporadic arrests, official assurances, and then silence.

Who spoke up and who didn’t

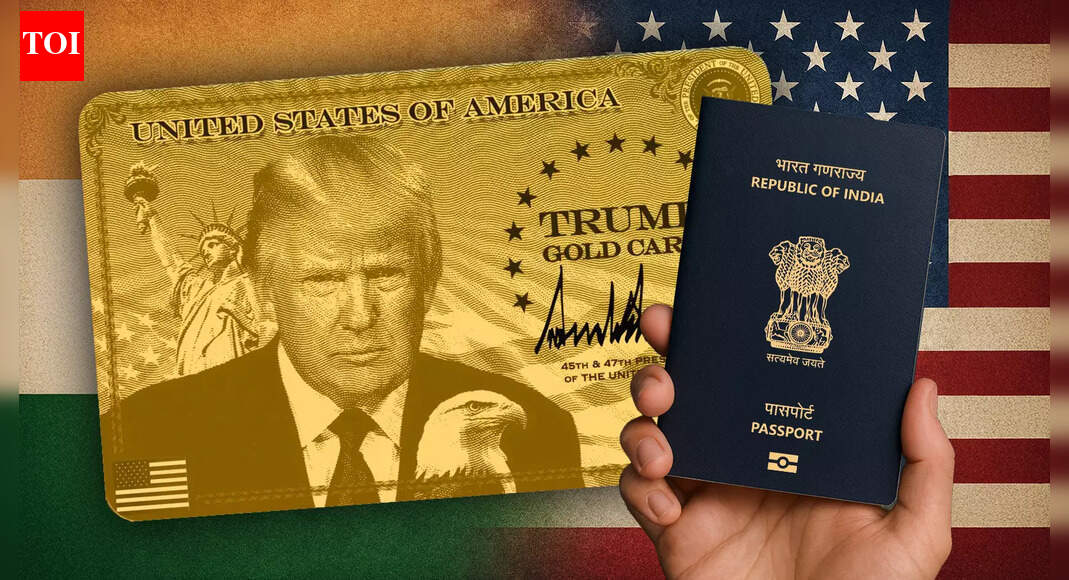

The violence did draw responses, but unevenly. Governments moved first. India publicly conveyed concern over the safety of minorities in Bangladesh and urged Dhaka to ensure accountability. The United Kingdom also issued statements condemning the killings and emphasising the need to protect vulnerable communities. These were formal, on-record reactions that acknowledged the gravity of the crimes. Local activists from Bangladesh, Hindu organisations, and diaspora members were much more outspoken. To prevent the problem from falling out of the public eye, they planned protests, gave police updates, identified victims, and documented instances.

What stood out was the relative quiet from major international human rights organisations, notably Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, unlike their response to conflicts such as Gaza, where both organisations issued rapid statements, detailed reports, emergency appeals, and sustained media briefings. The attacks against Hindus in Bangladesh did not trigger comparable mobilisation. The contrast is visible not only at the organisational level but also among high-profile global activists.

Not a single prominent activist like Greta Thunberg, who has been outspoken and highly active on Gaza-related issues, even on political issues like the farmer protests in India, have not issued public statements on the recent killings of Hindus in Bangladesh. Public statements are still a big thing; she has not made a single tweet about these atrocities. The same silence applies to several other prominent international activists who regularly comment on human rights crises worldwide. There were no stand-alone investigations, no urgent global campaigns, and no continuous public briefings explicitly focused on these killings. Where Bangladesh was referenced, it was mainly within broader thematic discussions, not as a crisis demanding immediate international pressure. This comparison is difficult to overlook. When governments and local civil society speak clearly, but the world’s most influential human rights watchdogs respond cautiously or minimally, especially when they have demonstrated the capacity for rapid action elsewhere, it raises an uncomfortable but legitimate question. It is about priority and which victims are considered worthy of ongoing international campaigning.

What silence actually Looks Like

In this context, silence does not mean the complete absence of words. It is more subtle and more consequential. It appears as the absence of focused attention. There have been no dedicated investigative reports centred specifically on the plight of Hindu victims in Bangladesh. There have been no emergency action alerts urging supporters worldwide to pressure authorities. And there has been no sustained international media push driven by NGO briefings that keeps the issue in circulation beyond the first news cycle. This stands in contrast to how global human rights organisations have responded to other episodes of mob violence or communal attacks elsewhere. In those cases, even before court proceedings conclude, NGOs often publish preliminary assessments, appoint spokespeople, issue rolling updates, and frame the violence as a test of state responsibility. The aim is not just documentation but momentum to ensure governments remain under constant scrutiny. In Bangladesh’s recent cases, that momentum never materialised. The killings briefly surfaced in regional reporting and social media, then receded from the international agenda. Without sustained amplification, diplomatic pressure weakens, public memory fades, and the victim’s life becomes a footnote rather than a catalyst for accountability.

Conclusion: When silence becomes a choice

The question raised by these killings is not whether global human rights organisations or prominent activists are obligated to respond to every act of violence. It is whether their selective urgency undermines the very universality they claim to defend. When the lynching of a religious minority confirmed by police, documented by media, and acknowledged by governments fails to trigger sustained global advocacy, the silence itself becomes questionable.

Human rights lose moral force when attention appears conditional. Advocacy loses credibility when outrage is immediate in some theatres but restrained or absent in others. For the victims and their families, this disparity is not academic, but it shapes whether justice is pursued with seriousness or allowed to dissolve into procedural formality and forgotten headlines.

Bangladesh’s Hindu minorities do not need symbolic sympathy or fleeting mentions in annual reports. They need the same consistency, urgency, and international pressure that global institutions readily deploy elsewhere. Until that happens, claims of universal human rights will continue to ring hollow, measured not by words issued, but by the silences that remain.