Where Did That Viral Carrot Salad Really Come From?

The story behind the salad, or morkovcha, is one of Korean culinary innovation, forcible exile, and a violent dictatorship

Last winter, a Ukrainian American wellness and lifestyle influencer named Danielle Zaslavsky posted a TikTok of herself slurping a grated carrot salad straight from a frosty mason jar. In the video, she eats with gusto, praising the salad’s salt and tang while she audibly crunches away. Her TikTok generated tens of millions of views and a flurry of comments from users demanding to know what exactly she was enjoying.

The answer? Morkovcha. Also known as koreyska, the salad is the creation of ethnic Koreans in the former Soviet Union, or Koryo-saram, who fled Japan’s colonial grip on their country during the early 1900s.

“I was genuinely surprised to learn how many people were unfamiliar with morkovcha, as it was a staple in my upbringing,” says Zaslavsky. “It is really meaningful ... to have the opportunity to share a piece of my heritage and personal experience with others.” The recipe she uses is from her great-aunt. “At the time, living in the former Soviet Union, all of the women knew how to make [morkovcha] because of the Koreans who immigrated to eastern Russia,” Zaslavsky explains. “There were many dishes that were inspired from their culture.”

Throughout the rest of 2024, Zaslavsky continued to post more morkovcha in repurposed glass jars, explaining how her great-aunt ferments the carrots with garlic, vinegar, oil, and red pepper. Although she shared each post with #koreancarrotsalad in her caption, her TikToks unfortunately never clarified why morkovcha is called Korean carrot salad (“morkovcha” is its Russian translation), let alone why her great-aunt, who grew up in the Soviet Union, holds deep appreciation for it. As Zaslavsky’s carrot salad videos gained popularity, other health- and wellness-conscious social media creators, as well as home cooks, began to upload their own renditions of the salad, opting to call it the “viral carrot salad” or even “Danielle’s carrot salad.” Korean, as an ethnicity and a descriptor, is erased from the dish in their captions.

This peculiar blip on the carrot salad radar reflects the way context collapses as recipes go viral and are reinterpreted.

Existing reportage of morkovcha frames it as a testament to the trade routes of Central Asia, and attributes its creation to the mass diasporic movement of Koreans into the Soviet Union. Much of it blithely compares the carrot salad to kimchi, and frames it as a homesick response to the loss of napa cabbage and fermented shrimp, two key ingredients in kimchi that were easily sourced in Korea.

But in reality, morkovcha is far from a feel-good story about an ethnic group’s adaptation to a new environment. Not long after tens of thousands Koreans resettled in eastern parts of the Soviet Union in the late 19th century, Koryo-saram were exiled to the western edges of Central Asia by then-Soviet leader Joseph Stalin. The regime, which was paranoid about the Japanese army’s encroachment on the USSR’s surrounding territories, considered the Koryo-saram “unreliable people.” To Stalin, Koreans looked too much like the Japanese to tell them apart, and driven by this racist logic, he embarked on a massive ethnic cleanse. Carted out by cattle cars to desolate grasslands or barren deserts of what is now Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, thousands of Koryo-saram died in transit, while thousands more died acclimating to their new, harsh living conditions.

While they lost their culture and language under Stalin’s regime, Koreans gained some economic leverage through collective agriculture with other ethnic groups who were being surveilled by Stalin, such as Kurds, Kazakhs, and Uzbeks. As great farmers, Koryo-saram were also able to recreate foods from their homeland once more.

“[Morkovcha] is rooted in the food culture of the collective farms during the Soviet times,” explains Y. David Chung, an artist and filmmaker who directed and produced a 2006 documentary called Koryo Saram: The Unreliable People. “It’s a dish refined from these collective farms where Koreans became known for growing onions, and the resulting food became a banchan mixed in with the Russian or Soviet way of making salads.”

Today, morkovcha is commonly found on the menus of Central Asian and Slavic restaurants in the United States, representing much of the immigration that happened in the early aughts after the last nations under the Soviet Union gained their independence. Cafe Lily, one of the most widely known Korean Uzbeki restaurants in New York, alongside Caravan and Eddie Fancy Food, prides itself on serving family-style cooking to Brooklyn’s growing Koryo-saram population. Sergey Pyagay, the eldest son of Cafe Lily owner Lilia Tyan, has noticed that the growing Uzbek population over the last 10 to 15 years has kept his mother’s humble restaurant buzzing with immigrant families. Pyagay and Tyan consider morkovcha a banchan, a simple side dish that comes with any order of their hearty, meat-forward entrees.

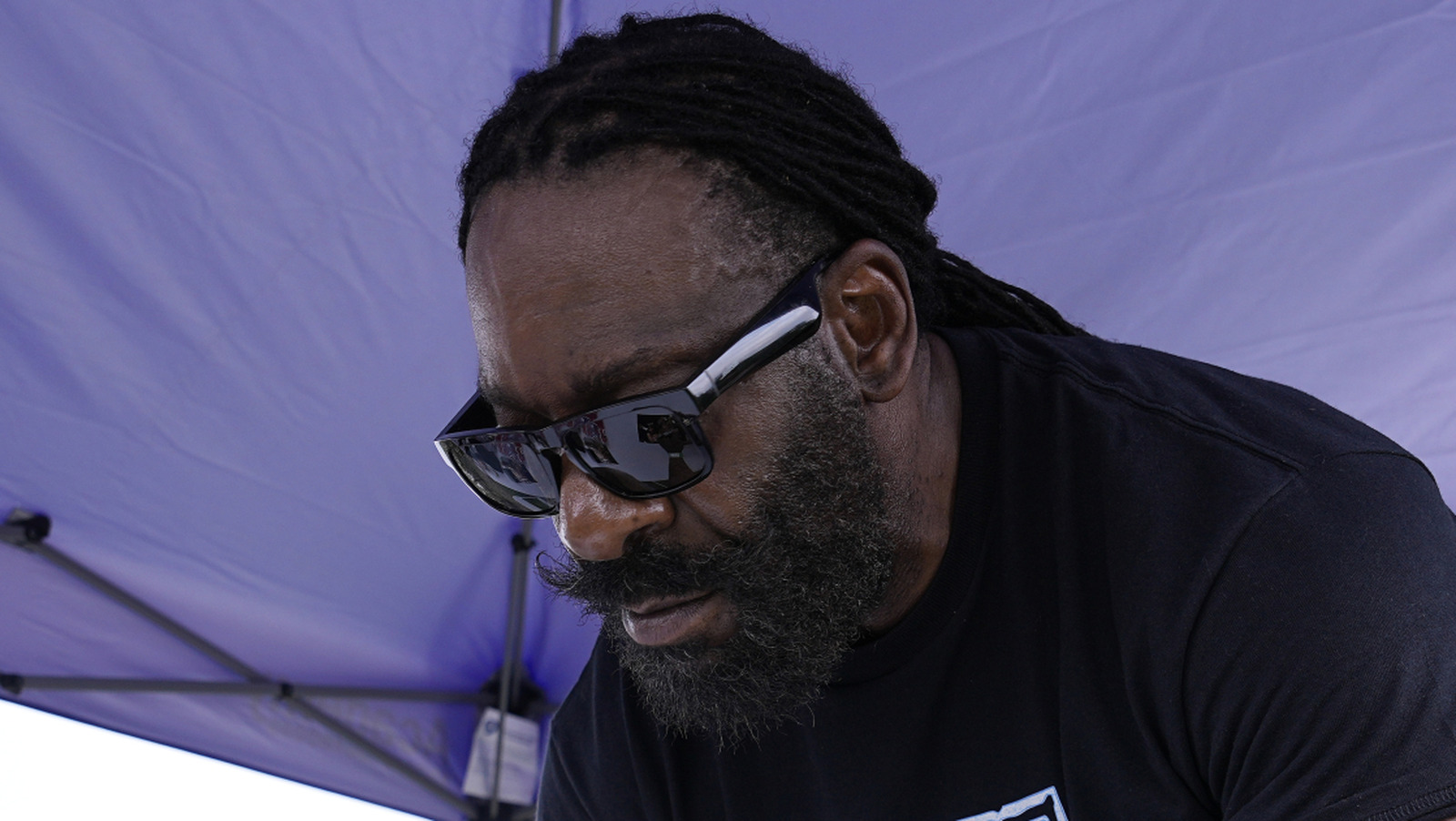

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25919969/MARKOVCHA.JPG) Maryna Haltseva

Maryna Haltseva

In the Los Angeles restaurant Zira Uzbek Kitchen, the Korean carrot salad is its own line on the menu, a welcoming sign to ethnic groups of Central Asia who now live in LA.

“I see a lot of second- or third-generation [Koryo-saram] who tell me this is the food they’ve known all their life,” says Azim Rahmatov, who recently opened the restaurant with his wife Gulnigor Ganieva and his brother Azam. “I have many Koreans from North Korea and South Korea who come after church, and they eat morkovcha with manti like there is no tomorrow because they have memories of eating them on the streets of Tashkent, or it’s what their mothers used to cook.”

Although it is served as a salad at Zira, Rahmatov also treats morkovcha as a banchan and recommends putting it on bacon-wrapped hot dogs for a quintessentially Los Angeles experience, an important expression of how people can take a dish with roots in suffering and integrate it into new places and contexts.

In Pittsburgh, a city that has credited new multicultural families for its recent economic boom and cultural revival, Takhmina Umaralieve, the owner of the Uzbek restaurant Kavsar, credits the city’s social media-savvy yinzers for a growing interest in Korean-Uzbek dishes such as morkovcha.

“I think people are drawn to its bold flavors, unique history, and the growing curiosity about global cuisines,” Umaralieva says. “Plus, the city’s diverse and curious food scene, especially among younger generations and newcomers, has contributed to its rising popularity.”

Of course, so many cultures love the carrot for its ubiquity and adaptability. Carrot salads, in their various forms, come and go in popularity. But morkovcha is a national dish that does not receive as much recognition as other more well-known Central Asian dishes, such as manti or shashlik.

As the Russian American food writer Anya von Bremzen affirms in her book National Dish: Around the World in Search of Food, History, and the Meaning of Home, human beings have a compulsion to tie food to place, but that compulsion lies more in marketing a nation than in historical fact. Because of this compulsion, morkovcha could never be a renowned national dish for Russia; it is a dish rooted in struggle and resilience despite the attempt to erase an ethnic group. If morkovcha could speak, it would be honest about how borders, deportations, and exile have tried to get rid of the people who created it. And yet, food is the one thing that still defies such manmade borders.

“When we are in collective groups, it’s only a matter of time before ethnic dishes simply travel across borders and find themselves in homes with different families,” Chung says. “It becomes an amazing cross-fertilization of mixed food and languages.”

While morkovcha currently serves as a bright-orange anomaly in healthy meal discourse among gut-conscious millennials, it ought to remind Americans that our favorite cultural recipes don’t exist in a social media vacuum to serve our wellness-minded interests. Many of them have intense histories worth sharing so that they are not rewritten.