Pakistan’s 40% ‘period tax’ challenged by young lawyer in the Supreme Court: How far behind is the Nation on menstrual hygiene?

Every month, millions of women go through menstruation, a simple biological process that’s as natural as breathing. Yet even today, society, policymakers, and the government treat it like a matter of shame or luxury. This attitude has now sparked a debate in Pakistan, led by a 25-year-old lawyer and activist, Mahnoor Omar. She has taken the government to court over what is being called the “period tax”: a total 40% levy on sanitary pads and menstrual hygiene products, including taxes and customs duties. Omar argues that these taxes, both direct and indirect, make sanitary pads unaffordable for millions of women, especially those living in poverty or rural areas. As she points out, menstruation is not a choice or privilege; it’s a natural, recurring part of every woman’s life. Taxing menstrual products, she says, is no different from taxing women for simply existing in their bodies. When pads are treated like luxury items The crux of the issue lies in how Pakistan’s tax system classifies sanitary pads. While products like cattle semen, milk, and cheese are tax-free, menstrual products are placed in the same category as perfumes and cosmetics, considered “luxury goods”, and are taxed heavily. This policy, activists say, is not only illogical but discriminatory. “How can something women need to maintain their health and dignity be seen as a luxury?” asks Mahnoor Omar. For her, it is not just a financial issue; it is one of respect, equality, and basic human rights. Several countries, including India, Kenya, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, Colombia, and South Africa, have already abolished the so-called “pink tax.” However, Pakistan has still not declared sanitary pads as essential commodities, an opportunity to underscore how deeply gender bias is embedded in policy-making. A tax that hurts women’s health The impact of this tax goes far beyond money. According to UNICEF and other public health reports, taxes have pushed the retail price of sanitary pads up by nearly 40%. This makes them unaffordable for a large share of Pakistan’s 109 million women. This results in only about 16% of women from rural settings using sanitary pads. The majority of them often revert to using old rags or any other unhygienic material. Such habits significantly increase the risk of infection and long-term reproductive health problems. During the floods of 2022, which destroyed basic supplies, women had to use whatever they could find under unsafe and unsanitary conditions. Doctors and health experts caution that this situation amounts to a silent public health crisis. Poor menstrual hygiene doesn’t just cause physical diseases; it also fuels increased mental stress, shame, and exclusion. Education is interrupted by period poverty Sanitary pads have also hit education hard. In rural and low-income communities, many girls miss school on days of their periods or lack proper access to hygienic products or clean toilets, with some dropping out altogether. Studies show that one in five girls in Pakistan misses school during her period. Over time, this means many lose nearly an entire academic year’s worth of classes. Surveys indicate that about 79% of women and girls say they cannot take part in school, work, or social activities during their periods. Even more shockingly, approximately 41% of girls do not know what menstruation is when it first happens to them. No one discusses it in the home or at school. And this silence engenders fear, confusion, and stigma, and continues to hold girls back from full participation in life and learning. The wall of shame and silence But beyond the economics, a deeper barrier remains-the cultural shame related to menstruation. In most parts of Pakistan, even today, periods are considered dirty, embarrassing, or taboo. Nobody speaks about them openly, not families, not teachers, not even policymakers. This wall of silence has translated into complete policy neglect. The government has no national menstrual health strategy, no comprehensive law, and no structured plan for menstrual hygiene management (MHH). This “policy vacuum,” as experts call it, keeps millions of women trapped in poor health and social exclusion. But young activists and civic groups are finally breaking this silence. Organisations like “Mahwari Justice” travel to underprivileged areas, educating the community, distributing pads, and teaching girls to understand their bodies with pride rather than shame. They reshape the thinking of society over the issue of menstruation with one conversation at a time. Sparks of change There are small but hopeful steps being taken. In Sindh province, school record systems have started including “menstrual facilities” as a key metric. This move aims to track whether schools are equipped with clean toilets, running water, and privacy for female students. Global organisations like UNICEF are pushing Pakistan’s government to cut or remove

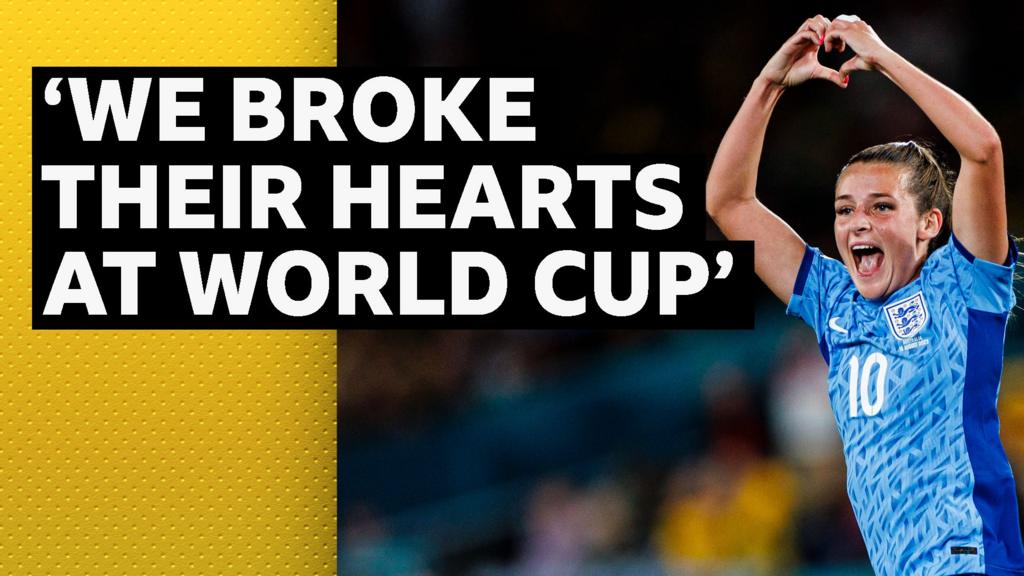

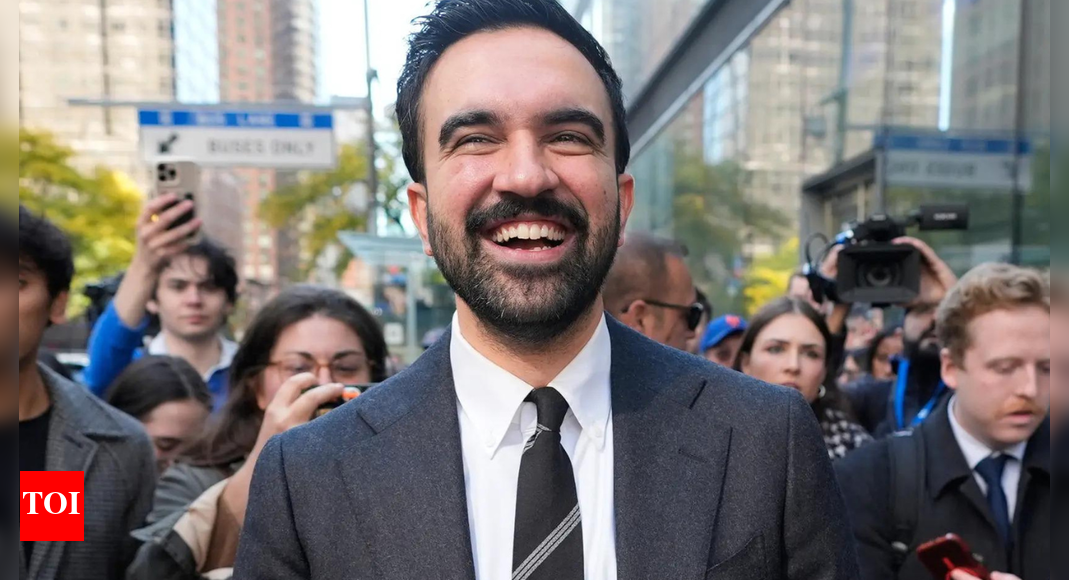

Every month, millions of women go through menstruation, a simple biological process that’s as natural as breathing. Yet even today, society, policymakers, and the government treat it like a matter of shame or luxury. This attitude has now sparked a debate in Pakistan, led by a 25-year-old lawyer and activist, Mahnoor Omar. She has taken the government to court over what is being called the “period tax”: a total 40% levy on sanitary pads and menstrual hygiene products, including taxes and customs duties.

Omar argues that these taxes, both direct and indirect, make sanitary pads unaffordable for millions of women, especially those living in poverty or rural areas. As she points out, menstruation is not a choice or privilege; it’s a natural, recurring part of every woman’s life. Taxing menstrual products, she says, is no different from taxing women for simply existing in their bodies.

When pads are treated like luxury items

The crux of the issue lies in how Pakistan’s tax system classifies sanitary pads. While products like cattle semen, milk, and cheese are tax-free, menstrual products are placed in the same category as perfumes and cosmetics, considered “luxury goods”, and are taxed heavily.

This policy, activists say, is not only illogical but discriminatory. “How can something women need to maintain their health and dignity be seen as a luxury?” asks Mahnoor Omar. For her, it is not just a financial issue; it is one of respect, equality, and basic human rights.

Several countries, including India, Kenya, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, Colombia, and South Africa, have already abolished the so-called “pink tax.” However, Pakistan has still not declared sanitary pads as essential commodities, an opportunity to underscore how deeply gender bias is embedded in policy-making.

A tax that hurts women’s health

The impact of this tax goes far beyond money. According to UNICEF and other public health reports, taxes have pushed the retail price of sanitary pads up by nearly 40%. This makes them unaffordable for a large share of Pakistan’s 109 million women.

This results in only about 16% of women from rural settings using sanitary pads. The majority of them often revert to using old rags or any other unhygienic material. Such habits significantly increase the risk of infection and long-term reproductive health problems. During the floods of 2022, which destroyed basic supplies, women had to use whatever they could find under unsafe and unsanitary conditions.

Doctors and health experts caution that this situation amounts to a silent public health crisis. Poor menstrual hygiene doesn’t just cause physical diseases; it also fuels increased mental stress, shame, and exclusion.

Education is interrupted by period poverty

Sanitary pads have also hit education hard. In rural and low-income communities, many girls miss school on days of their periods or lack proper access to hygienic products or clean toilets, with some dropping out altogether.

Studies show that one in five girls in Pakistan misses school during her period. Over time, this means many lose nearly an entire academic year’s worth of classes. Surveys indicate that about 79% of women and girls say they cannot take part in school, work, or social activities during their periods.

Even more shockingly, approximately 41% of girls do not know what menstruation is when it first happens to them. No one discusses it in the home or at school. And this silence engenders fear, confusion, and stigma, and continues to hold girls back from full participation in life and learning.

The wall of shame and silence

But beyond the economics, a deeper barrier remains-the cultural shame related to menstruation. In most parts of Pakistan, even today, periods are considered dirty, embarrassing, or taboo. Nobody speaks about them openly, not families, not teachers, not even policymakers.

This wall of silence has translated into complete policy neglect. The government has no national menstrual health strategy, no comprehensive law, and no structured plan for menstrual hygiene management (MHH). This “policy vacuum,” as experts call it, keeps millions of women trapped in poor health and social exclusion.

But young activists and civic groups are finally breaking this silence. Organisations like “Mahwari Justice” travel to underprivileged areas, educating the community, distributing pads, and teaching girls to understand their bodies with pride rather than shame. They reshape the thinking of society over the issue of menstruation with one conversation at a time.

Sparks of change

There are small but hopeful steps being taken. In Sindh province, school record systems have started including “menstrual facilities” as a key metric. This move aims to track whether schools are equipped with clean toilets, running water, and privacy for female students.

Global organisations like UNICEF are pushing Pakistan’s government to cut or remove the taxes on menstrual products entirely. Their message is clear: menstrual hygiene is not a luxury, it’s a basic health and human right.

The petition filed by Mahnoor Omar in court has fueled this debate, and no policymaker can afford to look the other way. Her legal fight is not about taxation but about changing the way society thinks about women’s bodies and needs.

The gender-blind policy problem

A central argument Omar raises is that government policies often suffer from what researchers call “gender-blindness.” This means that laws and economic strategies are created from a male perspective, without fully considering how policies affect women differently.

For example, when policymakers decide on tax rates, their main concern is usually government revenue. They rarely think about who will bear that financial burden. In the case of the period tax, it is women who pay both literally and symbolically.

Her case aims to change that mindset and push the government to adopt gender-sensitive policymaking, where women’s everyday realities shape national decisions.

Why should the sanitary tax be removed?

The first and foremost point is that menstruation is a natural process, not a hobby or luxury for which women should have to pay extra tax. Sanitary pads are a basic necessity for women, just like food, clothing, and shelter. They are directly related to women’s health, hygiene, and dignity. When the government imposes a tax on them, it fails to recognise them as essential items. This clearly reflects discrimination.

Why removing the tax isn’t enough

While eliminating the period tax would be an important victory, activists believe it’s only one part of a much bigger challenge. True menstrual justice requires tackling both the financial and social barriers that hurt women and girls.

That means breaking the cultural taboo, ensuring menstrual education in schools, and building proper sanitation facilities everywhere, especially in public schools and rural areas. Many schools in Pakistan still lack private toilets or clean water, forcing girls to stay home every month.

Only when these facilities and open conversations become normal can Pakistan achieve what activists call “period equity”, a society where no girl or woman is ashamed or held back because of her biology.

The bigger picture: Dignity, health, and rights

At its heart, this movement isn’t just about removing a tax; it’s about demanding dignity. Menstrual hygiene products are as essential as food, clothing, or housing. Treating them as optional luxuries degrades the basic health rights of women.

Every woman spends an estimated six to seven years of her life menstruating. To make her pay extra for that reality is to burden her for simply being female. This financial penalty reflects deep gender inequality and must end if Pakistan truly wants to move forward.

As Omar and her fellow activists put it, menstrual health is not a private or secondary issue; it’s a public, social, and human rights issue. And ignoring it means ignoring half the country’s population.