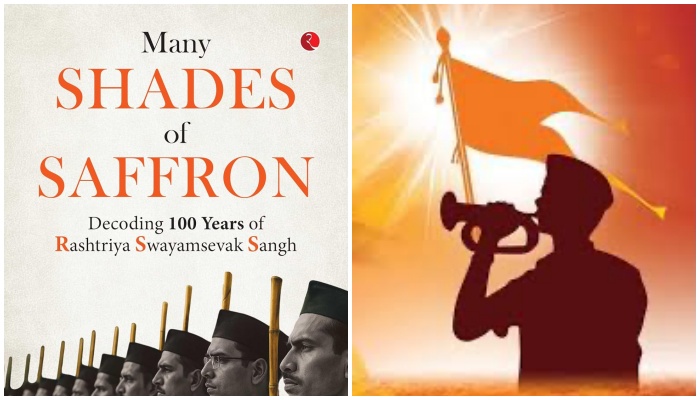

‘Many Shades of Saffron’ by Chandrachur Ghose: Understanding the RSS through a century of growth in the complex socio-political landscape of India

In Many Shades of Saffron, Chandrachur Ghose takes on one of the most popular and impactful institutions in modern India, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), and does so with scholarly patience, historical rigor, and a welcome willingness to avoid ideological grandstanding. The timing of this work is particularly significant: the year 2025 marks the centenary of both the RSS and the Communist Party of India (CPI). Though both organisations emerged in the same historical moment of anti-colonial ferment, their worldviews, institutional trajectories, and relationships with the Indian state diverged dramatically. Ghose uses this moment of shared origin not to draw forced parallels, but to illuminate the deeper ideological, cultural, and political contrasts between the two. The CPI arose from Marxist-Leninist intellectual currents, rooted in class struggle and global revolutionary consciousness. Many Shades of Saffron, however, begins with the founding of the RSS in Nagpur on the culturally significant occasion of Vijaya Dashami, a choice that demonstrates the value of civilizational symbolism and cultural memory in the organisation’s worldview. K.B. Hedgewar envisioned the RSS not as a political movement but as a long-term social and cultural force dedicated to national regeneration. Where the CPI built cadres through study circles, ideological training, and policy debates, the RSS relied on daily shakhas, personal discipline, collective identity, and character formation. Ghose makes clear that these differing pedagogies would, over time, shape not only the internal cultures of the two organisations but also their destinies. One of the most compelling themes in Many Shades of Saffron is the contrast in documentation practices. The communist tradition has always been meticulous resolutions, congress reports, polemical texts, biographies, and ideological treatises, forming a vast and easily accessible archive. The RSS, however, was slow to document itself. Hedgewar believed that a living example carried greater power than a written declaration, and it was only after 1950 that the organization adopted a formal constitution. This lack of documentation contributed to a perception of secrecy and opacity, especially among scholars and political commentators. But as Ghose argues, the lack of documentation was less a deliberate strategy of concealment than a reflection of cultural priorities: the Sangh sought to live values rather than codify them. Ghose’s treatment of the RSS leadership over a century is another of the book’s strengths. Figures such as MS Golwalkar, Balasaheb Deoras, Rajendra Singh, and Mohan Bhagwat are presented neither as icons nor as villains, but as thinkers and organisers shaped by the pressures of their times. The book tracks how the Sangh responded to major national developments, the struggle for independence, the trauma of Partition, the Emergency, the rise of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), and the turbulent politics of the Ram Janmabhoomi movement. Throughout, the organisation’s ability to adapt while maintaining a coherent internal identity emerges as a key reason for its longevity. If the CPI’s history is one of splits CPI(M), CPI(ML), and further ideological micronizations, the RSS story is one of expansion. Today, the Sangh Parivar encompasses dozens of affiliated organisations spanning education, labour, farmer groups, tribal upliftment, women’s participation, religious reform, and electoral politics. Ghose does not exaggerate this influence, nor does he apologise for it. He simply traces how the RSS, originally dismissed by both colonial administrators and nationalist leaders, grew into one of the most consequential cultural forces in the world’s largest democracy. Significantly, Many Shades of Saffron addresses the polarised landscape of literature surrounding the RSS. Insider accounts have often been devotional, while outsider critiques have tended to be suspicious, even hostile. Both have contributed to a climate in which the RSS is either heroised or demonised, with little space for historical nuance. Ghose consciously avoids both traps. He neither glosses over contentious episodes nor indulges in ideological denunciation. His goal is not to judge but to understand a rarity in the study of Indian political organisations today. The prose is accessible and measured, suitable for the serious general reader as well as students and scholars of contemporary Indian politics. Rather than overwhelming the reader with detail, Ghose selects key turning points and thematic continuities, always situating events in broader cultural and political shifts. His methodology respects both archival research and lived organisational experience. Some readers may wish for deeper engagement with questions of secularism, pluralism, and minoritarian anxieties. Ghose addresses these issues, but he prioritizes historical context over ideological debate. Instead, he gives readers

In Many Shades of Saffron, Chandrachur Ghose takes on one of the most popular and impactful institutions in modern India, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), and does so with scholarly patience, historical rigor, and a welcome willingness to avoid ideological grandstanding. The timing of this work is particularly significant: the year 2025 marks the centenary of both the RSS and the Communist Party of India (CPI).

Though both organisations emerged in the same historical moment of anti-colonial ferment, their worldviews, institutional trajectories, and relationships with the Indian state diverged dramatically. Ghose uses this moment of shared origin not to draw forced parallels, but to illuminate the deeper ideological, cultural, and political contrasts between the two.

The CPI arose from Marxist-Leninist intellectual currents, rooted in class struggle and global revolutionary consciousness. Many Shades of Saffron, however, begins with the founding of the RSS in Nagpur on the culturally significant occasion of Vijaya Dashami, a choice that demonstrates the value of civilizational symbolism and cultural memory in the organisation’s worldview. K.B. Hedgewar envisioned the RSS not as a political movement but as a long-term social and cultural force dedicated to national regeneration. Where the CPI built cadres through study circles, ideological training, and policy debates, the RSS relied on daily shakhas, personal discipline, collective identity, and character formation. Ghose makes clear that these differing pedagogies would, over time, shape not only the internal cultures of the two organisations but also their destinies.

One of the most compelling themes in Many Shades of Saffron is the contrast in documentation practices. The communist tradition has always been meticulous resolutions, congress reports, polemical texts, biographies, and ideological treatises, forming a vast and easily accessible archive. The RSS, however, was slow to document itself. Hedgewar believed that a living example carried greater power than a written declaration, and it was only after 1950 that the organization adopted a formal constitution. This lack of documentation contributed to a perception of secrecy and opacity, especially among scholars and political commentators. But as Ghose argues, the lack of documentation was less a deliberate strategy of concealment than a reflection of cultural priorities: the Sangh sought to live values rather than codify them.

Ghose’s treatment of the RSS leadership over a century is another of the book’s strengths. Figures such as MS Golwalkar, Balasaheb Deoras, Rajendra Singh, and Mohan Bhagwat are presented neither as icons nor as villains, but as thinkers and organisers shaped by the pressures of their times. The book tracks how the Sangh responded to major national developments, the struggle for independence, the trauma of Partition, the Emergency, the rise of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), and the turbulent politics of the Ram Janmabhoomi movement. Throughout, the organisation’s ability to adapt while maintaining a coherent internal identity emerges as a key reason for its longevity.

If the CPI’s history is one of splits CPI(M), CPI(ML), and further ideological micronizations, the RSS story is one of expansion. Today, the Sangh Parivar encompasses dozens of affiliated organisations spanning education, labour, farmer groups, tribal upliftment, women’s participation, religious reform, and electoral politics. Ghose does not exaggerate this influence, nor does he apologise for it. He simply traces how the RSS, originally dismissed by both colonial administrators and nationalist leaders, grew into one of the most consequential cultural forces in the world’s largest democracy.

Significantly, Many Shades of Saffron addresses the polarised landscape of literature surrounding the RSS. Insider accounts have often been devotional, while outsider critiques have tended to be suspicious, even hostile. Both have contributed to a climate in which the RSS is either heroised or demonised, with little space for historical nuance. Ghose consciously avoids both traps. He neither glosses over contentious episodes nor indulges in ideological denunciation. His goal is not to judge but to understand a rarity in the study of Indian political organisations today.

The prose is accessible and measured, suitable for the serious general reader as well as students and scholars of contemporary Indian politics. Rather than overwhelming the reader with detail, Ghose selects key turning points and thematic continuities, always situating events in broader cultural and political shifts. His methodology respects both archival research and lived organisational experience.

Some readers may wish for deeper engagement with questions of secularism, pluralism, and minoritarian anxieties. Ghose addresses these issues, but he prioritizes historical context over ideological debate. Instead, he gives readers the historical and institutional context necessary to form their own opinions. This restraint may frustrate those accustomed to polemical writing, but it is the very quality that makes the book valuable.

Many Shades of Saffron is not just a study of the RSS, it is a study of modern India itself. To understand the Sangh is to understand a major force shaping the political and cultural imagination of the country today. Ghose’s work is thus a vital contribution to the ongoing conversation about national identity, civilizational continuity, and the meaning of democracy in India.

This book is a must-read for supporters and critics of the RSS alike, for scholars, journalists, students, and every citizen seeking to understand the forces that have shaped and continue to shape the Indian republic.