From one-child policy to condom tax: Why China’s pro-birth policies are failing and why India should pay attention

China was associated with population control for many years. Family life was shaped for generations by the one-child policy, which was more than just a rule. It was a system enforced through law, incentives, and pressure. Contraception was encouraged, births were discouraged, and the government firmly intervened in reproductive decisions. When a country that once controlled births starts taxing condoms Today, that legacy has now completed a full circle. In a striking reversal, condoms and oral birth control pills are now more expensive in China. Due to the country’s dramatic reversal of tax exemption on contraception. The small message conveys a louder voice that the country that once worked to limit births is now anxious about having too few. This policy change is motivated by statistics rather than morals or philosophy. A shrinking, ageing population is beginning to threaten China’s economic momentum and future stability. The deeper question this raises goes beyond China: what happens when individual choices to delay or avoid parenthood make economic sense but, collectively, leave nations struggling to sustain themselves? Why China is pushing for babies urgently China’s urgency to boost the births stems from harsh demographic realities. After decades of strict population control, its fertility rate has dropped to around 1.15 children per woman. It is far below the replacement level of 2.1 needed to sustain a stable population. China has recorded a population decline for the last 3 years, even as deaths outnumber births. At the same time, more than 20% of the population is aged 60 or above. which is also adding pressure to public finances, healthcare, and the pension system. Because of a shrinking workforce and slowing economic growth, Beijing is more concerned about the possibility of “getting old before rich”, a situation in which a country faces the costs of ageing without the economic productivity to sustain them. The long shadow of the one-child policy For more than 30 years, China’s one-child policy did more than restrict family size. It has fundamentally reshaped societal behaviour and individual aspirations. The policy was introduced in 1980. This programme embedded state control deep into private life, turning reproduction into a monitored act. With time, small families were not just enforced but normalised. Having one child or none became the default, while larger families came to be viewed as impractical, risky, or even irresponsible. As a result of this protracted programme, marriages were postponed, and childbirth was pushed farther into adulthood as couples modified their goals to fit economic and political constraints. The costs of raising kids become more expensive alongside urbanisation and the psychological and emotional damage caused by aggressive enforcement like forced abortions, sterilisations, and invasive surveillance. Importantly, it also undermines the public confidence in the government regarding issues related to reproduction and family. After the policy was scrapped and replaced with two-child and three-child norms, behaviour did not immediately change. The larger lesson is clear: laws can change policy, but social conditioning built over many generations cannot be swiftly or easily reversed. Why pro-birth policies are struggling to work In an effort to reverse the fertility rate, the Chinese government has implemented several pro-birth initiatives in recent years. These include promises to eliminate out-of-pocket hospital delivery costs, expand childcare subsidies, offer cash incentives for families with young children, and increase access to public preschools. Universities have been urged to support good messaging about marriage and family life. Removed the administrative barriers to marriage registration. However, fertility rates have continued to decline despite these attempts. A basic drawback of state involvement is shown by the discrepancy between policy goals and societal responses. While marketing campaigns can signal official goals and financial incentives can lower certain immediate costs, they cannot address underlying concerns about work-life balance, housing affordability, job stability, and economic security. The other side: Why young couples are hesitant To understand why pro-birth policies are failing, it is necessary to look beyond the country’s intent and focus on the reality of the couples’ faces every day. In China’s major cities, housing prices have risen far faster thanincomes. Turning home ownership, a traditional requirement for marriage, has become an unattainable dream. Childcare and education costs add another layer of financial pressure, with the quality of schools, daycare, and extracurricular activities demanding sustained spending over decades. With slowing economic growth, it is becoming harder to plan long-term. Long working hours and demanding corporate cultures leave little room for family

China was associated with population control for many years. Family life was shaped for generations by the one-child policy, which was more than just a rule. It was a system enforced through law, incentives, and pressure. Contraception was encouraged, births were discouraged, and the government firmly intervened in reproductive decisions.

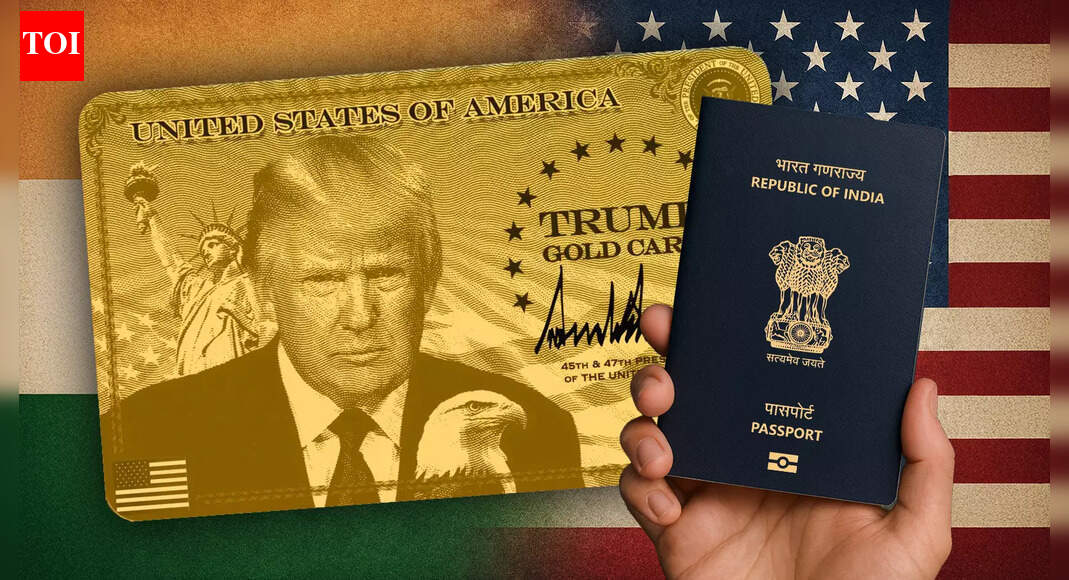

When a country that once controlled births starts taxing condoms

Today, that legacy has now completed a full circle. In a striking reversal, condoms and oral birth control pills are now more expensive in China. Due to the country’s dramatic reversal of tax exemption on contraception. The small message conveys a louder voice that the country that once worked to limit births is now anxious about having too few.

This policy change is motivated by statistics rather than morals or philosophy. A shrinking, ageing population is beginning to threaten China’s economic momentum and future stability. The deeper question this raises goes beyond China: what happens when individual choices to delay or avoid parenthood make economic sense but, collectively, leave nations struggling to sustain themselves?

Why China is pushing for babies urgently

China’s urgency to boost the births stems from harsh demographic realities. After decades of strict population control, its fertility rate has dropped to around 1.15 children per woman. It is far below the replacement level of 2.1 needed to sustain a stable population. China has recorded a population decline for the last 3 years, even as deaths outnumber births.

At the same time, more than 20% of the population is aged 60 or above. which is also adding pressure to public finances, healthcare, and the pension system.

Because of a shrinking workforce and slowing economic growth, Beijing is more concerned about the possibility of “getting old before rich”, a situation in which a country faces the costs of ageing without the economic productivity to sustain them.

The long shadow of the one-child policy

For more than 30 years, China’s one-child policy did more than restrict family size. It has fundamentally reshaped societal behaviour and individual aspirations. The policy was introduced in 1980. This programme embedded state control deep into private life, turning reproduction into a monitored act. With time, small families were not just enforced but normalised. Having one child or none became the default, while larger families came to be viewed as impractical, risky, or even irresponsible.

As a result of this protracted programme, marriages were postponed, and childbirth was pushed farther into adulthood as couples modified their goals to fit economic and political constraints. The costs of raising kids become more expensive alongside urbanisation and the psychological and emotional damage caused by aggressive enforcement like forced abortions, sterilisations, and invasive surveillance. Importantly, it also undermines the public confidence in the government regarding issues related to reproduction and family. After the policy was scrapped and replaced with two-child and three-child norms, behaviour did not immediately change. The larger lesson is clear: laws can change policy, but social conditioning built over many generations cannot be swiftly or easily reversed.

Why pro-birth policies are struggling to work

In an effort to reverse the fertility rate, the Chinese government has implemented several pro-birth initiatives in recent years. These include promises to eliminate out-of-pocket hospital delivery costs, expand childcare subsidies, offer cash incentives for families with young children, and increase access to public preschools. Universities have been urged to support good messaging about marriage and family life. Removed the administrative barriers to marriage registration.

However, fertility rates have continued to decline despite these attempts. A basic drawback of state involvement is shown by the discrepancy between policy goals and societal responses. While marketing campaigns can signal official goals and financial incentives can lower certain immediate costs, they cannot address underlying concerns about work-life balance, housing affordability, job stability, and economic security.

The other side: Why young couples are hesitant

To understand why pro-birth policies are failing, it is necessary to look beyond the country’s intent and focus on the reality of the couples’ faces every day. In China’s major cities, housing prices have risen far faster thanincomes. Turning home ownership, a traditional requirement for marriage, has become an unattainable dream. Childcare and education costs add another layer of financial pressure, with the quality of schools, daycare, and extracurricular activities demanding sustained spending over decades.

With slowing economic growth, it is becoming harder to plan long-term. Long working hours and demanding corporate cultures leave little room for family life, while dual-income households become a necessity rather than a choice. For women, it is much harsher. Despite high levels of education and workforce participation, childcare and household responsibilities continue to fall disproportionately on them, often at the cost of career progression and financial independence. In such conditions, parenthood is perceived not as a natural next step but as a high-risk decision. For many young couples, delaying or avoiding children feels economically rational, not irresponsible. An attempt to preserve stability in an increasingly uncertain future.

Beyond China: A global pattern, not a Chinese exception

China’s demographic struggle is not an isolated case but part of a broader global pattern visible across advanced economies. South Korea offers the starkest example. Despite being one of the world’s wealthiest nations and spending billions of dollars on cash incentives, childcare subsidies, housing support, and even state-sponsored matchmaking, it now has the lowest fertility rate in the world. Japan, too, has poured resources into family support programmes, yet continues to record falling birth rates, declining marriage rates, and a rapidly ageing population.

These cases underline a crucial reality: that economic prosperity and generous incentives alone are not enough to reverse fertility decline once it becomes deeply embedded in social behaviour. When delayed marriage, child-free living, and career-first priorities harden into norms, policy tools lose their effectiveness.

The lesson from East Asia is sobering. Once demographic decline becomes structural rather than cyclical, reversal becomes extraordinarily difficult. Therefore, timing matters far more than the spending.

India enters the picture quietly but clearly

What China, Japan, and South Korea have been grappling with for years, India is now beginning to enter the demographic conversations. According to the recent data, India’s total fertility rate has slipped below the replacement level of 2.1. It marks a significant shift for a country long associated with population growth. At the same time, the average age of marriage and first childbirth is rising steadily, particularly in urban and semi-urban areas.

In India’s major cities, East Asian patterns are beginning to appear. Young couples are postponing marriage, prioritising education and careers, and increasingly opting for smaller families or none at all. High housing costs, competitive job markets, and the growing necessity of dual-income households are reshaping traditional family timelines.

This does not yet amount to a demographic crisis. India still has a relatively young population and a sizeable working-age base. However, it is no longer insulated from the forces driving fertility decline elsewhere. The early signs suggest that without timely course correction, India could find itself confronting the same challenges now haunting East Asia.

The cost of not having children for India

India’s demographic story has long been framed as an advantage, with a young population and a large workforce driving growth. However, as fertility rates fall and family sizes shrink, that advantage risks gradually turning into a liability. A sustained decline in births would mean a smaller working-age population in the decades ahead, even as the number of elderly citizens continues to rise. This shift carries clear economic implications. Fewer workers will be required to support a larger dependent population, placing pressure on public finances, pension systems, and healthcare infrastructure.

The demographic dividend that once fuelled growth could slowly give way to demographic drag, in which productivity slows, and fiscal burdens increase. Beyond economics, an ageing society also faces social challenges, including changing family structures and an increased demand for care and support systems. These outcomes are not immediate or catastrophic, but they are cumulative. Left unaddressed, they can reshape growth trajectories and strain institutions over time.

Conclusion: Between Two Costs, a Narrow Window

There is no simple choice in the population debate. For families, having children has become increasingly expensive, uncertain, and emotionally demanding. For nations, however, not having enough children carries its own long-term costs, like economic, social, and structural ones. The challenge lies in navigating this tension without coercion or denial.

China’s experience shows what happens when demographic correction comes too late, after social habits have already hardened. India can still learn from those models, but the time for slow, careful action is running out. The decisions taken today will determine whether future generations inherit demographic balance or demographic strain.