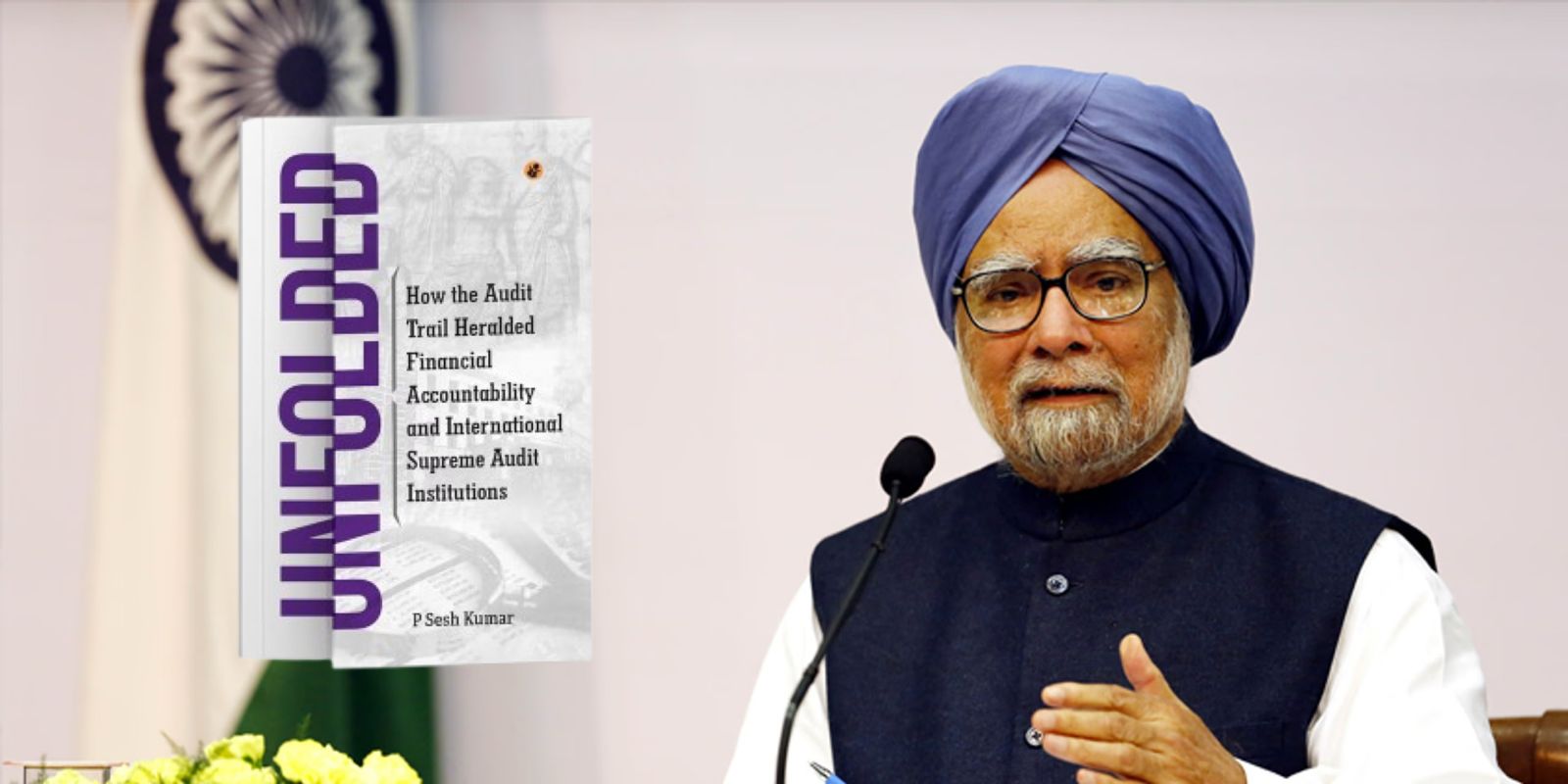

The stinking room of accountability: UPA under Manmohan Singh tried to muzzle the CAG over the Coalgate scam, new book by P Sesh Kumar reveals

When the watchdog of India’s finances refused to bow to political power, it was met with filth, smears, and institutional sabotage. In the annals of India’s democratic institutions, few episodes reveal the audacity of political power and the resilience of institutional integrity as vividly as the Coal Block Allocation Scam, popularly known as Coalgate. It was not merely a case of corruption or inefficiency. It was, at its heart, a battle between constitutional morality and political expediency, between the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) of India, the constitutional watchdog of the public purse, and the powerful political machinery of the then United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government led by Dr. Manmohan Singh. And as P. Sesh Kumar’s remarkable new book, Unfolded: How the Audit Trail Heralded Financial Accountability and International Supreme Audit Institution, reveals, the price of integrity was humiliation, isolation, and even stench. Quite literally. The Stinking Room of Power Kumar, who served as Director General of Audit in the CAG during the coal block audit, recounts how his team, tasked with one of the most consequential audits in India’s history, was assigned a small, dingy room next to a stinking toilet in the Coal Ministry. The intent was not lost on anyone. It was a message from the establishment: you are not welcome here. “The audit was not welcomed. They saw us as a nuisance,” Kumar told News18. “We were given a small room next to a stinking toilet. Toilets may have improved now, but they were stinking then.”This was the state of governance under an economist prime minister who often prided himself on “institutional independence.” The CAG’s team was investigating the opaque process through which coal blocks, India’s valuable natural resource, were allocated to private players. What they unearthed would shake the foundations of the UPA regime: a potential windfall gain of ₹1.86 lakh crore to private companies, caused by the government’s arbitrary and non-transparent allocation method. The ₹1.86 Lakh Crore Bombshell Contrary to the UPA’s claims of “speculative math,” Kumar’s book reveals that the figure was neither plucked from thin air nor politically motivated. It was grounded in data from Coal India Ltd., covering 57 out of 75 private coal block allocations. The auditors calculated extractable reserves, applied industry-standard price-cost data, and made conservative adjustments for expenses. Every assumption was disclosed transparently. “The CAG disclosed its assumptions upfront. Anyone questioning the figure could test those assumptions,” Kumar notes.The auditors never claimed that ₹1.86 lakh crore was a direct loss. It was a foregone opportunity, a quantifiable measure of how much the exchequer could have earned had the coal blocks been auctioned transparently, as later upheld by the Supreme Court when it cancelled all such allocations. The now-famous phrase “windfall gain,” Kumar reveals, wasn’t even coined by the CAG. It came from an internal note by the then Coal Secretary, who admitted that the allocation process had the potential of conferring “windfall gains” on private firms. The CAG merely quantified what the government’s own files already acknowledged. The Hidden Files and the Ministry of Stonewalls The process of unearthing the truth, however, was anything but smooth. The auditors faced stonewalling, non-cooperation, and even missing records. Out of more than 200 Screening Committee meetings where crucial decisions on coal allocations were made, the CAG’s team got access to just two or three sets of minutes. The message was clear: the government had much to hide. Kumar writes of how files mysteriously disappeared, delays were engineered, and bureaucratic obstacles were piled high to frustrate the audit. And yet, the auditors persevered. Working through holidays like Durga Puja, the team continued to dig until one day, they stumbled upon a policy file that would become the cornerstone of the entire scandal. This file contained internal communications dating back to 2004, including notes by the Coal Secretary, the Law Ministry, and even the Prime Minister himself, who briefly held the coal portfolio. It revealed that as early as 2006, the Law Ministry had cleared the concept of competitive bidding for coal blocks. Yet, inexplicably, the government sat on it for years, preferring the opaque and discretionary allocation route that benefited a few private players. That discovery demolished the UPA’s defense that auctions were “legally impossible” at the time. The truth, as the CAG report exposed, was far simpler: the system was designed to benefit the chosen few. The Political Counterattack The reaction from the corridors of power was swift and vicious. Then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, who had carefully cultivated the image of a clean technocrat, spoke against the CAG report in Parliament. Senior ministers held press c

In the annals of India’s democratic institutions, few episodes reveal the audacity of political power and the resilience of institutional integrity as vividly as the Coal Block Allocation Scam, popularly known as Coalgate. It was not merely a case of corruption or inefficiency. It was, at its heart, a battle between constitutional morality and political expediency, between the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) of India, the constitutional watchdog of the public purse, and the powerful political machinery of the then United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government led by Dr. Manmohan Singh.

And as P. Sesh Kumar’s remarkable new book, Unfolded: How the Audit Trail Heralded Financial Accountability and International Supreme Audit Institution, reveals, the price of integrity was humiliation, isolation, and even stench. Quite literally.

The Stinking Room of Power

Kumar, who served as Director General of Audit in the CAG during the coal block audit, recounts how his team, tasked with one of the most consequential audits in India’s history, was assigned a small, dingy room next to a stinking toilet in the Coal Ministry. The intent was not lost on anyone. It was a message from the establishment: you are not welcome here.

“The audit was not welcomed. They saw us as a nuisance,” Kumar told News18. “We were given a small room next to a stinking toilet. Toilets may have improved now, but they were stinking then.”

This was the state of governance under an economist prime minister who often prided himself on “institutional independence.”

The CAG’s team was investigating the opaque process through which coal blocks, India’s valuable natural resource, were allocated to private players. What they unearthed would shake the foundations of the UPA regime: a potential windfall gain of ₹1.86 lakh crore to private companies, caused by the government’s arbitrary and non-transparent allocation method.

The ₹1.86 Lakh Crore Bombshell

Contrary to the UPA’s claims of “speculative math,” Kumar’s book reveals that the figure was neither plucked from thin air nor politically motivated. It was grounded in data from Coal India Ltd., covering 57 out of 75 private coal block allocations. The auditors calculated extractable reserves, applied industry-standard price-cost data, and made conservative adjustments for expenses. Every assumption was disclosed transparently.

“The CAG disclosed its assumptions upfront. Anyone questioning the figure could test those assumptions,” Kumar notes.

The auditors never claimed that ₹1.86 lakh crore was a direct loss. It was a foregone opportunity, a quantifiable measure of how much the exchequer could have earned had the coal blocks been auctioned transparently, as later upheld by the Supreme Court when it cancelled all such allocations.

The now-famous phrase “windfall gain,” Kumar reveals, wasn’t even coined by the CAG. It came from an internal note by the then Coal Secretary, who admitted that the allocation process had the potential of conferring “windfall gains” on private firms. The CAG merely quantified what the government’s own files already acknowledged.

The Hidden Files and the Ministry of Stonewalls

The process of unearthing the truth, however, was anything but smooth. The auditors faced stonewalling, non-cooperation, and even missing records. Out of more than 200 Screening Committee meetings where crucial decisions on coal allocations were made, the CAG’s team got access to just two or three sets of minutes.

The message was clear: the government had much to hide. Kumar writes of how files mysteriously disappeared, delays were engineered, and bureaucratic obstacles were piled high to frustrate the audit.

And yet, the auditors persevered. Working through holidays like Durga Puja, the team continued to dig until one day, they stumbled upon a policy file that would become the cornerstone of the entire scandal.

This file contained internal communications dating back to 2004, including notes by the Coal Secretary, the Law Ministry, and even the Prime Minister himself, who briefly held the coal portfolio. It revealed that as early as 2006, the Law Ministry had cleared the concept of competitive bidding for coal blocks. Yet, inexplicably, the government sat on it for years, preferring the opaque and discretionary allocation route that benefited a few private players.

That discovery demolished the UPA’s defense that auctions were “legally impossible” at the time. The truth, as the CAG report exposed, was far simpler: the system was designed to benefit the chosen few.

The Political Counterattack

The reaction from the corridors of power was swift and vicious. Then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, who had carefully cultivated the image of a clean technocrat, spoke against the CAG report in Parliament. Senior ministers held press conferences branding the findings as “deeply flawed” and “misleading.”

The intent was unmistakable to discredit the institution, not the numbers.

The Congress’s political machinery and its friendly media ecosystem unleashed a smear campaign against the CAG and its then head, Vinod Rai. They were painted as “politically motivated,” “anti-growth,” and “anti-UPA.” It was an attempt to delegitimize the very idea of independent audit scrutiny.

But history has been kinder to the auditors. The Supreme Court later vindicated the CAG’s findings, calling the coal allocations “arbitrary and illegal” and cancelling all 214 coal block allocations made between 1993 and 2010. The constitutional watchdog had been right all along.

The Real Meaning of the Coal Audit

Kumar’s book reminds us that the CAG’s coal audit was never about numbers alone. It was about principles of transparency, accountability, and the sanctity of public resources. In a democracy, natural resources belong to the people, not the political class or their corporate cronies.

By exposing how a secretive Screening Committee parceled out coal blocks without competitive bidding, the CAG restored faith in the very idea of constitutional oversight. It proved that even in an era of political dominance and media manipulation, institutions could stand tall if led by men and women of conviction.

“The real victory was not in a number printed on a report,” Kumar writes, “but in reaffirming that accountability in public finance is not an act of politics, it is an act of democracy.”

A Lesson for Our Times

The coal scam saga and the shabby treatment meted out to the CAG team should serve as a sobering lesson for all those who talk glibly about “independent institutions.” Under the UPA, the institutions of accountability were not strengthened; they were stifled. When the CAG did its job, it was ridiculed and harassed. When investigative agencies probed corruption, they were accused of being “politicized.”

And yet, despite the filth, both literal and metaphorical, the auditors in that stinking room held their ground. Their courage ensured that India’s democracy did not lose its moral compass.

Today, as India continues to build a more transparent and accountable governance model under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, it is worth remembering the CAG’s fight during the UPA era. It was not just a fight for clean audits; it was a fight for clean governance.

The smell from that toilet room in the Coal Ministry may have faded with time, but it remains a metaphor for what the CAG stood against: the stench of corruption and political deceit. And in standing firm, the CAG ensured that the Constitution, not the coalition, had the final word.