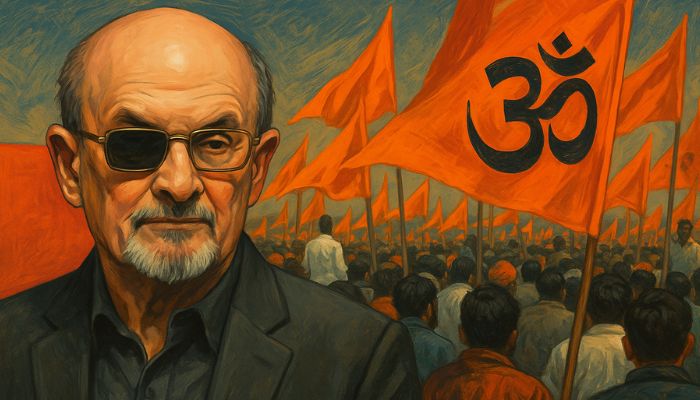

Salman Rushdie, who lost his eye to Islamic radicalism, expresses concern about ‘Hindu nationalism’ in India: Read why his virtue signalling is misplaced

On 5th December, Bloomberg published its interview with author Salman Rushdie conducted by British presenter Mishal Husain. Interestingly, Mishal, who has family roots in Pakistan, has family ties to Rushdie and it was explicitly acknowledged in their conversation. Husain’s mother and Rushdie were first cousins, making the interaction a blend of journalistic inquiry and intra-family reminiscence. The interview covered Rushdie’s recovery after the 2022 stabbing, his writing, his memories of Bombay (now Mumbai), and his reflections on free speech. Yet, when the subject shifted towards India under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, his responses began to echo a familiar script shaped not by recent engagements (the ban on his book The Satanic Verses has been lifted under the Modi government) or first-hand experience. His views, which he openly admitted, were the impressions given to him by his “journalist friends” in India. It is these second-hand interpretations, and the ideological leanings that come with them, that now appear to underpin his concerns about the world’s largest democracy. Rushdie’s views on India shaped by selectively informed ‘journalist friends’ In the interview, Rushdie stated that he feels “very worried” about India today. However, this concern was not rooted in personal observation. It was based on the “information” he received from his journalist friends based in India. This admission is crucial, because it reveals that his commentary is built upon the very ecosystem that has spent a decade constructing a narrative of democratic decline in India. These are the voices that have shouted “press freedom crisis” and “free speech under threat” at every turn, even as India’s media remains among the most vibrant, adversarial and politically diverse landscapes in the world. Interestingly, the journalist friends of Rushdie who told him freedom of speech of journalists is under threat continue to speak against PM Modi consistently without much legal backlash from the government, and they have been doing it since he took charge as the Prime Minister of the country. Drawing solely from the conversations with his friends, Rushdie claimed that journalists, writers, professors and intellectuals face “attacks on freedom” in India. He suggested that the Indian state wishes to “rewrite history” to cast Hindus as inherently virtuous and Muslims as inherently villainous. He even compared the present era to Indira Gandhi’s Emergency, a period of actual dictatorship involving mass arrests, censorship and suspension of civil liberties. His framing of India into this pre-decided mould reflects less about the country and more about the narrow ideological lens through which his sources view it. The ease with which he repeated these talking points, despite not having visited India in years, showed how detached such intellectual critiques have become from the lived reality of ordinary Indians. Why his claim of ‘attacks on journalists’ falls apart upon basic scrutiny The notion that India’s press is under siege is one of the most carefully manufactured narratives of the past decade. Rushdie adopted the line of thought which is entirely based on left-liberal activist-journalists who have internationalised their personal legal troubles. It exposed how misinformation, which was once laundered through the Lutyens media circle, has emerged as unquestioned truth. In the Indian context, the face of this narrative has often been the likes of Rana Ayyub, who has repeatedly described herself as being “targeted” for her writings. However, she was never actually attacked by the government agencies for what she wrote. She came under scrutiny and faced legal troubles because of alleged financial impropriety, including misappropriation of funds raised in the name of COVID-19 relief and charity. The action taken by the government agencies against her was detailed and procedural, not ideological. She was not targeted because of what she wrote but because of what she did with the money she had collected to “help the poor”. Not to forget, when Rushdie was attacked by an Islamist in 2022, Rana Ayyub had condemned it. However, after facing backlash from her fellow Islamists, she “corrected her mistake” and deleted the post from social media platform. Rushdie’s adoption of this line, which is entirely based on activist-journalists who have internationalised their personal legal troubles, exposes how misinformation spreads. Yet the myth of a persecuted journalist persists because it suits the political appetites of those who weaponise victimhood. Another example that comes to mind is the case of Siddique Kappan that has been repeatedly cited by international media as a “journalist jailed for doing his job”. The reality, established in court documents and investigation reports, is significantly different. PFI-linked Kappan was detained while travelling to Hathras during a highly sensitive period, all

On 5th December, Bloomberg published its interview with author Salman Rushdie conducted by British presenter Mishal Husain. Interestingly, Mishal, who has family roots in Pakistan, has family ties to Rushdie and it was explicitly acknowledged in their conversation. Husain’s mother and Rushdie were first cousins, making the interaction a blend of journalistic inquiry and intra-family reminiscence.

The interview covered Rushdie’s recovery after the 2022 stabbing, his writing, his memories of Bombay (now Mumbai), and his reflections on free speech. Yet, when the subject shifted towards India under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, his responses began to echo a familiar script shaped not by recent engagements (the ban on his book The Satanic Verses has been lifted under the Modi government) or first-hand experience. His views, which he openly admitted, were the impressions given to him by his “journalist friends” in India. It is these second-hand interpretations, and the ideological leanings that come with them, that now appear to underpin his concerns about the world’s largest democracy.

Rushdie’s views on India shaped by selectively informed ‘journalist friends’

In the interview, Rushdie stated that he feels “very worried” about India today. However, this concern was not rooted in personal observation. It was based on the “information” he received from his journalist friends based in India. This admission is crucial, because it reveals that his commentary is built upon the very ecosystem that has spent a decade constructing a narrative of democratic decline in India.

These are the voices that have shouted “press freedom crisis” and “free speech under threat” at every turn, even as India’s media remains among the most vibrant, adversarial and politically diverse landscapes in the world. Interestingly, the journalist friends of Rushdie who told him freedom of speech of journalists is under threat continue to speak against PM Modi consistently without much legal backlash from the government, and they have been doing it since he took charge as the Prime Minister of the country.

Drawing solely from the conversations with his friends, Rushdie claimed that journalists, writers, professors and intellectuals face “attacks on freedom” in India. He suggested that the Indian state wishes to “rewrite history” to cast Hindus as inherently virtuous and Muslims as inherently villainous. He even compared the present era to Indira Gandhi’s Emergency, a period of actual dictatorship involving mass arrests, censorship and suspension of civil liberties.

His framing of India into this pre-decided mould reflects less about the country and more about the narrow ideological lens through which his sources view it. The ease with which he repeated these talking points, despite not having visited India in years, showed how detached such intellectual critiques have become from the lived reality of ordinary Indians.

Why his claim of ‘attacks on journalists’ falls apart upon basic scrutiny

The notion that India’s press is under siege is one of the most carefully manufactured narratives of the past decade. Rushdie adopted the line of thought which is entirely based on left-liberal activist-journalists who have internationalised their personal legal troubles. It exposed how misinformation, which was once laundered through the Lutyens media circle, has emerged as unquestioned truth.

In the Indian context, the face of this narrative has often been the likes of Rana Ayyub, who has repeatedly described herself as being “targeted” for her writings. However, she was never actually attacked by the government agencies for what she wrote. She came under scrutiny and faced legal troubles because of alleged financial impropriety, including misappropriation of funds raised in the name of COVID-19 relief and charity.

The action taken by the government agencies against her was detailed and procedural, not ideological. She was not targeted because of what she wrote but because of what she did with the money she had collected to “help the poor”.

Not to forget, when Rushdie was attacked by an Islamist in 2022, Rana Ayyub had condemned it. However, after facing backlash from her fellow Islamists, she “corrected her mistake” and deleted the post from social media platform.

Rushdie’s adoption of this line, which is entirely based on activist-journalists who have internationalised their personal legal troubles, exposes how misinformation spreads. Yet the myth of a persecuted journalist persists because it suits the political appetites of those who weaponise victimhood.

Another example that comes to mind is the case of Siddique Kappan that has been repeatedly cited by international media as a “journalist jailed for doing his job”. The reality, established in court documents and investigation reports, is significantly different. PFI-linked Kappan was detained while travelling to Hathras during a highly sensitive period, allegedly to provoke unrest. The charges involved conspiracy and terror-related activities, not journalism. Courts examined the matter extensively, and while he eventually secured bail, the framing of the case as a press freedom issue remains misleading.

Let’s not forget The Wire journalist Arfa Khanum Sherwani, who repeatedly claims a decline of freedom of speech and expression while continuing to spew venom against Hindus and India. Let’s not forget that in January 2020, she advised protesting Muslims to appear inclusive as part of a strategy. She said that there was no doubt that when Muslims were protesting against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), they were primarily protesting as Muslims, but they must try to appear inclusive in order to not lose the battle. “You must make these protests as inclusive as you could and make its base bigger. You read your Kalmas, do the Ibadat, the Indian Constitution is still present in that manner. But when you come out in the public, you are a Muslim, there is no doubt about it,” she had said.

Another example can be of Umar Khalid, a so-called student activist currently in jail for his involvement in the anti-Hindu Delhi riots of 2020. Khalid, who is often presented as an “intellectual”, has been painted as a hero in the international media thanks to narrative-building exercises run by the likes of The Wire, Scroll and others. Umar Khalid, whose father was a member of the banned terrorist outfit SIMI, is booked under UAPA in the larger conspiracy case. He and his friends in prison in the same case have been delaying the trial and even bail pleas in different courts and blaming the system for keeping them behind bars for over five years without trial. Such narratives, when fed to international figures like Rushdie, often create anti-Indian government sentiments.

His selective silence on the ideology that actually attempted to kill him

What makes Rushdie’s commentary on India more revealing than his opinions themselves is the fact that he did not criticise Islamic radicalism, the very force that has repeatedly sought to end his life.

In the interview, he spoke about the fatwa as a historical moment and acknowledged the brutality of the 2022 stabbing, but he stopped short of examining the ideology that motivated the attacker. Maybe that was the intent of the interview from the beginning considering the interviewer’s own background.

For someone who lost an eye, endured severe injuries and continues to live with the trauma inflicted by religious extremism, this reticence is stark. He did not mention mullahs who have issued calls for violence, radical clerics who continue to inflame sentiments, or the persistent threat posed by Islamist extremism worldwide. Instead, he chose to analyse and criticise the fabric of Hindu society, despite having no comparable personal history of persecution from it.

The imbalance raises questions about intellectual courage and the political fashion of selective criticism. Rushdie was far more willing to critique India’s social climate, a place where he grew freely and safely, than to address the continuing threat emanating from the ideology that turned him into a symbol of resistance.

His vague references to the fatwa era contrast sharply with his pointed commentary on Hindu nationalism, as though one must be handled delicately while the other can be freely lectured upon without consequence.

His reflections on Indira Gandhi and the Emergency reveal an odd imbalance

Rushdie also revisited his portrayal of the Emergency in Midnight’s Children. He described it as a “dark time” that deeply affected the country and shaped the arc of his novel. He acknowledged the shock felt by many Indians at the abrogation of democratic rights during Indira Gandhi’s rule.

Yet, in the same breath, he implied that today’s India bears similarities to that period. This comparison rang hollow when juxtaposed with the functioning of contemporary India, where elections remain competitive, newspapers publish fierce criticism daily, courts strike down government decisions routinely, and no constitutional rights have been suspended.

The Emergency was a structurally authoritarian moment in India’s history. Equating it with present-day democratic functioning trivialises a lived trauma experienced by millions. Rushdie’s analogy appears to stem from the ideological environment he now inhabits rather than any substantive parallel.

The irony of invoking Naipaul without acknowledging Naipaul’s fuller critique

In the interview, Rushdie referred to VS Naipaul’s phrase “a wounded civilisation” to support his argument that the current Indian discourse on history is driven by a civilisation trying to reclaim something lost. Yet he stopped just where Naipaul becomes inconvenient for the narrative he is endorsing.

Naipaul’s work did not merely observe India’s wounded state. It explored how centuries of colonisation, first Islamic then British, had eroded cultural confidence. Naipaul also recognised the emergence of a Hindu civilisational revival as a legitimate response to historical suppression. While one may disagree with his conclusions, Naipaul’s critique was complex, layered and deeply rooted in field observations. Rushdie, however, extracts only the part that suits the ideological discomfort expressed by his journalist acquaintances.

Conclusion

Rushdie’s commentary on India mirrors Western anxieties rather than Indian reality. It fits neatly into the binary lens through which Western media and academic institutions tend to view the country. Instead of engaging with India’s vibrant democratic processes, cultural plurality and civilisational resurgence, Rushdie relied on selectively informed English-speaking intermediaries who are themselves uneasy with India’s political direction.

Having lived in New York and London for decades, he has absorbed perspectives that interpret the rise of Hindu cultural confidence not as democratic expression but as democratic decline. His critique of “Hindu nationalism” reflected the discomfort with the fact that India is no longer shaped exclusively by the old “elite” classes that once dominated its intellectual space.

This imbalance is amplified by his dependence on second-hand accounts from journalist friends who frame India’s democracy as a threat simply because it does not mirror Western expectations. The contradiction becomes sharper when juxtaposed with his free speech advocacy. While he defended the right to offend, he avoided confronting the ideology that nearly killed him and instead repeated narratives that portray Hindu assertion as dangerous. Ultimately, his concerns reveal more about his intellectual distance and borrowed anxieties than about India.