Modi govt’s big boost to data centres in Budget 2026: Read how global cloud giants are being welcomed to invest in India, and why some domestic players are concerned

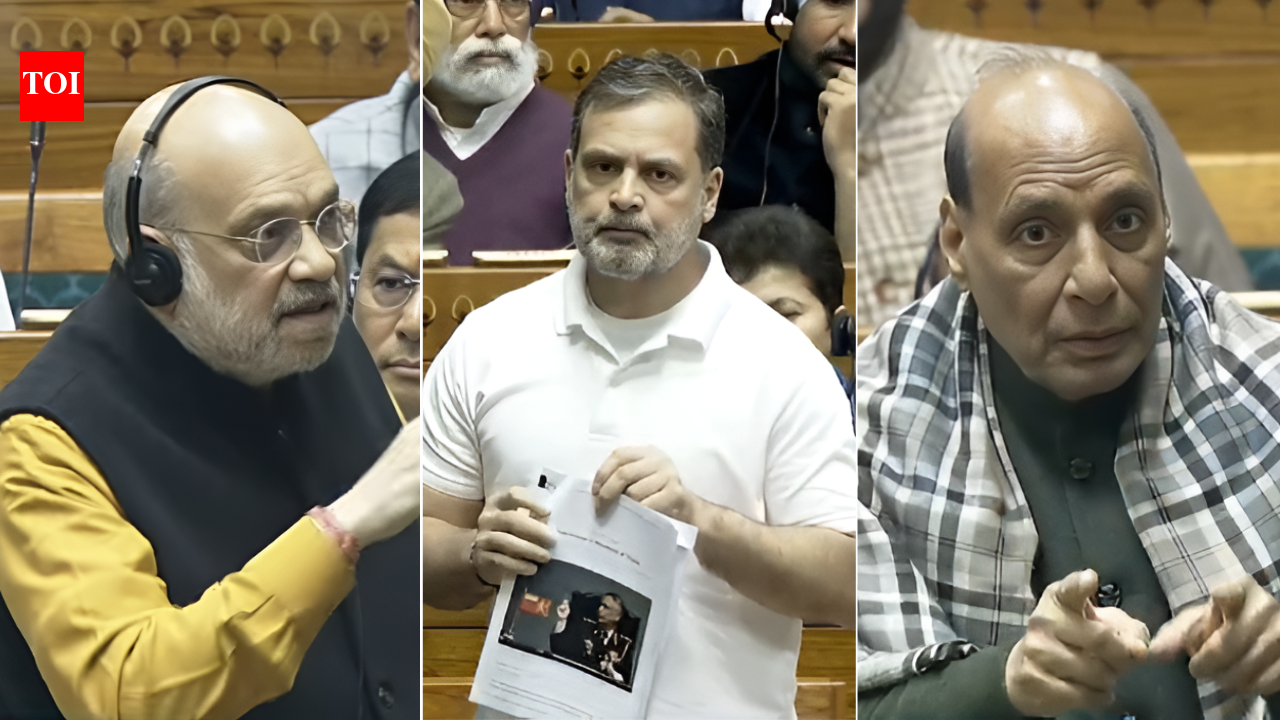

On 1st February, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman announced the Union Budget 2026, which introduced a decisive policy shift aimed at accelerating India’s rise as a global hub for data centres, cloud computing and AI infrastructure. At the heart of the announcement made by the Modi government is a long-term tax holiday framework designed to attract foreign investment while preserving India’s domestic tax base. Tax holiday till 2047 for global cloud firms serving the world from India.#ViksitBharatBudget pic.twitter.com/XqvHVlRgrB— Nirmala Sitharaman Office (@nsitharamanoffc) February 1, 2026 Foreign companies that procure data centre services from specified data centres located in India will be exempt from paying tax in India on income earned from serving customers outside the country until 31st March 2047. Revenue earned from Indian users, however, must be routed through an Indian reseller entity and taxed domestically. The Budget also introduced a 15% safe harbour margin on costs for related party data centre services. This move is intended to reduce transfer pricing disputes and offer predictability to multinational companies planning large-scale infrastructure investments in India. Most importantly, the framework addresses a long-standing concern among foreign companies, the risk that hosting workloads in India could create a taxable permanent establishment. With the announcement, the government has removed a major hurdle to FDI in the sector. Why the move matters for foreign companies and FDI Data centres are capital-intensive assets with long gestation periods. For companies dealing in cloud services, hyperscaling and artificial intelligence, policy certainty often outweighs short-term tax incentives. As the Indian government has extended the tax holiday up to 2047, it has effectively invited global technology firms to treat India as a long-term infrastructure base rather than a short-term outsourcing destination. This move has come at a time when AI workloads are expanding rapidly and are expected to account for a substantial share of global data centre capacity over the next decade. Notably, India is already generating around 20% of the world’s data but hosts only a fraction of global data centre capacity. Lower build costs, a large pool of technical talent, and improving power and connectivity infrastructure make India commercially attractive. Along with this, the new tax framework removes backend tax friction while ensuring that domestic consumption remains within the Indian tax net through the reseller requirement. From a policy perspective, the move balances investment attraction with fiscal prudence, a key reason why it has been welcomed by global investors and industry observers. The government’s strategic intent The Economic Survey for 2025–26 clearly stated that India’s future competitiveness in information technology depends on how effectively it integrates AI development, cloud infrastructure and digital trade into its growth strategy. When viewed in this context, the data centre tax framework is not a standalone concession. It is part of a broader attempt to reposition India within global digital supply chains, moving from being a major data generator to a serious infrastructure provider. The requirement that specified data centres must be owned and operated by Indian entities and notified by the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology ensures that physical infrastructure control remains within the country, even as global workloads flow in. Why Indian innovators are raising concerns While the policy’s intent is clear, it has triggered concerns among sections of India’s domestic cloud and data centre ecosystem, particularly homegrown providers who have been investing for years without similar fiscal incentives. Speaking to OpIndia, Manoj Dhanda, Founder and CTO of Utho Cloud, acknowledged that foreign investment will raise infrastructure standards and bring capital into the ecosystem. However, he pointed out that Indian data centres and cloud companies have been operating under the existing tax regime for years, investing in infrastructure, research and platform development without comparable support from the government. Dhanda argued that mandating foreign companies to serve Indian customers only through Indian resellers risks reinforcing a model where Indian firms remain intermediaries, while core technology, intellectual property and strategic control continue to sit overseas. In his view, India has spent the last decade and a half reselling global digital services such as email platforms, cloud and AI tools. According to him, the Budget does little to break that pattern, even as the government increasingly emphasises building and innovating within India. Speaking to OpIndia, Vinay Murarka, Founder of V2Technosys and a long-time industry observer, expressed similar reservations, albeit from a policy design standpo

On 1st February, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman announced the Union Budget 2026, which introduced a decisive policy shift aimed at accelerating India’s rise as a global hub for data centres, cloud computing and AI infrastructure. At the heart of the announcement made by the Modi government is a long-term tax holiday framework designed to attract foreign investment while preserving India’s domestic tax base.

Tax holiday till 2047 for global cloud firms serving the world from India.#ViksitBharatBudget pic.twitter.com/XqvHVlRgrB

— Nirmala Sitharaman Office (@nsitharamanoffc) February 1, 2026

Foreign companies that procure data centre services from specified data centres located in India will be exempt from paying tax in India on income earned from serving customers outside the country until 31st March 2047. Revenue earned from Indian users, however, must be routed through an Indian reseller entity and taxed domestically.

The Budget also introduced a 15% safe harbour margin on costs for related party data centre services. This move is intended to reduce transfer pricing disputes and offer predictability to multinational companies planning large-scale infrastructure investments in India.

Most importantly, the framework addresses a long-standing concern among foreign companies, the risk that hosting workloads in India could create a taxable permanent establishment. With the announcement, the government has removed a major hurdle to FDI in the sector.

Why the move matters for foreign companies and FDI

Data centres are capital-intensive assets with long gestation periods. For companies dealing in cloud services, hyperscaling and artificial intelligence, policy certainty often outweighs short-term tax incentives.

As the Indian government has extended the tax holiday up to 2047, it has effectively invited global technology firms to treat India as a long-term infrastructure base rather than a short-term outsourcing destination. This move has come at a time when AI workloads are expanding rapidly and are expected to account for a substantial share of global data centre capacity over the next decade.

Notably, India is already generating around 20% of the world’s data but hosts only a fraction of global data centre capacity. Lower build costs, a large pool of technical talent, and improving power and connectivity infrastructure make India commercially attractive.

Along with this, the new tax framework removes backend tax friction while ensuring that domestic consumption remains within the Indian tax net through the reseller requirement.

From a policy perspective, the move balances investment attraction with fiscal prudence, a key reason why it has been welcomed by global investors and industry observers.

The government’s strategic intent

The Economic Survey for 2025–26 clearly stated that India’s future competitiveness in information technology depends on how effectively it integrates AI development, cloud infrastructure and digital trade into its growth strategy.

When viewed in this context, the data centre tax framework is not a standalone concession. It is part of a broader attempt to reposition India within global digital supply chains, moving from being a major data generator to a serious infrastructure provider.

The requirement that specified data centres must be owned and operated by Indian entities and notified by the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology ensures that physical infrastructure control remains within the country, even as global workloads flow in.

Why Indian innovators are raising concerns

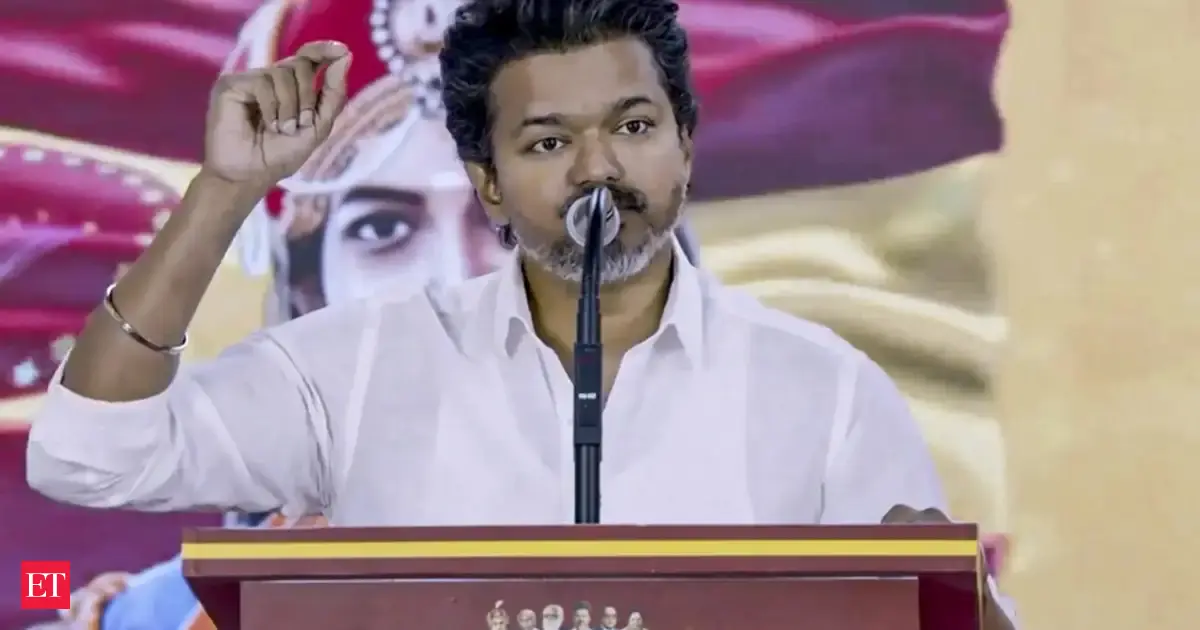

While the policy’s intent is clear, it has triggered concerns among sections of India’s domestic cloud and data centre ecosystem, particularly homegrown providers who have been investing for years without similar fiscal incentives.

Speaking to OpIndia, Manoj Dhanda, Founder and CTO of Utho Cloud, acknowledged that foreign investment will raise infrastructure standards and bring capital into the ecosystem. However, he pointed out that Indian data centres and cloud companies have been operating under the existing tax regime for years, investing in infrastructure, research and platform development without comparable support from the government.

Dhanda argued that mandating foreign companies to serve Indian customers only through Indian resellers risks reinforcing a model where Indian firms remain intermediaries, while core technology, intellectual property and strategic control continue to sit overseas.

In his view, India has spent the last decade and a half reselling global digital services such as email platforms, cloud and AI tools. According to him, the Budget does little to break that pattern, even as the government increasingly emphasises building and innovating within India.

Speaking to OpIndia, Vinay Murarka, Founder of V2Technosys and a long-time industry observer, expressed similar reservations, albeit from a policy design standpoint rather than opposition to foreign investment itself.

While Murarka supported the government’s push to attract global data centre capacity and recognised the importance of tax certainty in drawing hyperscalers and international cloud players to India, he believes the framework stopped short of addressing the asymmetry between foreign platforms and domestic innovators.

According to his assessment, while foreign companies benefit from long-term tax exemptions and reduced compliance risk, Indian cloud and data centre providers receive no parallel incentive, despite the fact that they have been bearing higher market risk and have invested early in building domestic capacity. He argued that this could unintentionally tilt the competitive landscape further in favour of established global players.

He also raised concerns that without targeted encouragement for Indian enterprises to host workloads on Indian cloud platforms, the policy may deepen India’s dependence on foreign-owned technology stacks, even if the physical infrastructure sits on Indian soil.

The opportunity the Budget did not seize

Both Dhanda and Murarka point to a missed opportunity. They argue that the government could have complemented its foreign investment push with time-bound incentives for Indian businesses that choose domestic cloud providers.

Even limited benefits for three to five years, they suggest, could have nudged enterprises to migrate workloads locally, bringing data control, platform development and intellectual property creation within India. Such an approach would not have diluted foreign investment but strengthened the domestic ecosystem alongside it.

A balanced reading of the policy

The data centre framework in Budget 2026 is neither anti-domestic industry nor uncritical globalisation. It is a calculated attempt to close India’s infrastructure gap and position the country as a serious player in the global AI and cloud economy.

At the same time, the concerns raised by Indian innovators are not ideological objections but structural questions about long-term value creation and technological sovereignty.

The real test of the policy will lie in its implementation and in whether future measures address these domestic gaps. If India can attract foreign capital while simultaneously nurturing homegrown cloud and data centre platforms, the country can move beyond being a hosting destination to becoming a true digital infrastructure power.