Kerala’s drug crisis: ‘God’s Own Country to ‘Ganja’s Own Hub’. Coastal trafficking, rapid spread and rising NDPS cases, explained

When the name ‘Kerala’ comes up, education and health often come to mind, thanks to extensively positive reporting on these two sectors by the left-leaning media. But is Kerala such a model state? Behind the curtains, and not in a hidden manner, Kerala is struggling with a drug epidemic. From cities to villages, not a single corner of the state is free from the problem. Hundreds of lives have been shattered, and families across the state have been broken as an outcome of the growing drug problem. Traditionally, Punjab is seen as India’s drug epicentre. However, recent reports paint a grim picture of Kerala. In 2024 alone, the state registered 27,700 narcotics cases, which is three times more than Punjab, which registered just over 9,000 cases. Considering the population of the southern coastal state, Kerala is reporting 78 cases per lakh people. Reportedly, all 14 districts of the state are affected. In the first two months of 2025, there were 30 murders reported in the state, half of which were related to drug abuse. According to data tabled in the Rajya Sabha on 12th March this year, Kerala has consistently topped the list of NDPS Act cases over the past three years. The state reported 26,918 cases in 2022, rising to 30,715 in 2023, and 27,701 in 2024. Punjab followed with 12,423, 11,564 and 9,025 cases respectively, while Maharashtra, Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh reported fluctuating but lower figures. The trend indicates Kerala’s dominance in narcotics-related offences, far exceeding traditional hotspots like Punjab. Source: Ministry of Home Affairs, Rajya Sabha Kerala, the picturesque state often called “God’s own country”, is in the grip of a drug crisis that is widespread and escalating. While law enforcement agencies are reportedly working extensively to control the drug problem, the path ahead seems dark and demands immediate attention. The rise of ‘420’ culture among youth In 1971, five high school friends used 4:20 PM as code for their cannabis-fuelled adventures. Over half a decade down the line, the “420 culture” boomed among youth worldwide, and Kerala’s young generation got hit as well. The “420 culture” has been adopted as a badge of rebellion by a section of Kerala’s young generation. As per media reports, slang and hashtags celebrating “420” are often seen on social media accounts of Kerala’s youth, reflecting a growing normalisation of cannabis use. Random posts and internet memes on social media platforms propagate the laid-back lifestyle of “stoners”, which is a clear signal that “420 culture” has become extremely popular among youth. Source: Instagram Cannabis, which is also known as ganja in local circles, is often treated as a mild drug. However, ground reports reveal it has become the gateway to deeper addiction. Many adolescent addicts said in their statements that their journey of becoming an addict began with casual ganja smoking in their school days, which rapidly turned into dangerous substances including MDMA, cocaine and marijuana. According to the authorities, the 420-driven drug culture is cheating Kerala’s children of their childhood and future. While parents assume school and college campuses are safe, they are quickly becoming the frontline of the epidemic. In one incident, excise officers in Idukki were stunned when a group of high school boys on a field trip wandered into their office asking for a matchbox to light a ganja-laced beedi. Several surveys have found shockingly high rates of experimentation among young school-going children. One government study indicated that over 37% of 10th graders and 23% of 8th graders in Kerala have tried an illegal drug or inhalant at least once. Cannabis is among the first choices. The local media has dubbed the epidemic “Udta Kerala”, taking inspiration from the movie Udta Punjab that depicted the rapidly increasing drug problem in the northern state. While drug addiction among Keralites begins with cannabis in most cases, it is still widely available. According to law enforcement agencies in the state, high-strength “hydroponic” cannabis with THC >40% has flooded Kerala’s market, making the 420 culture even more potent. This hybrid ganja does not grow in fields but in labs. It is often smuggled in from Southwest Asia. In fact, the smuggling of this type of ganja was essentially nil in 2022, but in 2024–25 alone, authorities seized over 89 kg from airports. In just seven months of 2025, the seizure rose to 129.7 kg. Notably, Thai-grown hydroponic cannabis is highly potent and can fetch as high as Rs 1 crore per kg in the international market. Interestingly, because there is high scrutiny by law enforcement agencies to stop cannabis from entering India, smugglers have reportedly shifted to Middle Eastern routes. The 420 culture may romanticise ganja, but today’s reality is a booming international trade in ultra-strong cannabis, ensnaring Kerala’s youth in a cycle of addiction. Why Kerala? Roo

When the name ‘Kerala’ comes up, education and health often come to mind, thanks to extensively positive reporting on these two sectors by the left-leaning media. But is Kerala such a model state? Behind the curtains, and not in a hidden manner, Kerala is struggling with a drug epidemic. From cities to villages, not a single corner of the state is free from the problem. Hundreds of lives have been shattered, and families across the state have been broken as an outcome of the growing drug problem.

Traditionally, Punjab is seen as India’s drug epicentre. However, recent reports paint a grim picture of Kerala. In 2024 alone, the state registered 27,700 narcotics cases, which is three times more than Punjab, which registered just over 9,000 cases. Considering the population of the southern coastal state, Kerala is reporting 78 cases per lakh people. Reportedly, all 14 districts of the state are affected. In the first two months of 2025, there were 30 murders reported in the state, half of which were related to drug abuse.

According to data tabled in the Rajya Sabha on 12th March this year, Kerala has consistently topped the list of NDPS Act cases over the past three years. The state reported 26,918 cases in 2022, rising to 30,715 in 2023, and 27,701 in 2024. Punjab followed with 12,423, 11,564 and 9,025 cases respectively, while Maharashtra, Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh reported fluctuating but lower figures. The trend indicates Kerala’s dominance in narcotics-related offences, far exceeding traditional hotspots like Punjab.

Kerala, the picturesque state often called “God’s own country”, is in the grip of a drug crisis that is widespread and escalating. While law enforcement agencies are reportedly working extensively to control the drug problem, the path ahead seems dark and demands immediate attention.

The rise of ‘420’ culture among youth

In 1971, five high school friends used 4:20 PM as code for their cannabis-fuelled adventures. Over half a decade down the line, the “420 culture” boomed among youth worldwide, and Kerala’s young generation got hit as well. The “420 culture” has been adopted as a badge of rebellion by a section of Kerala’s young generation.

As per media reports, slang and hashtags celebrating “420” are often seen on social media accounts of Kerala’s youth, reflecting a growing normalisation of cannabis use. Random posts and internet memes on social media platforms propagate the laid-back lifestyle of “stoners”, which is a clear signal that “420 culture” has become extremely popular among youth.

Cannabis, which is also known as ganja in local circles, is often treated as a mild drug. However, ground reports reveal it has become the gateway to deeper addiction. Many adolescent addicts said in their statements that their journey of becoming an addict began with casual ganja smoking in their school days, which rapidly turned into dangerous substances including MDMA, cocaine and marijuana.

According to the authorities, the 420-driven drug culture is cheating Kerala’s children of their childhood and future. While parents assume school and college campuses are safe, they are quickly becoming the frontline of the epidemic. In one incident, excise officers in Idukki were stunned when a group of high school boys on a field trip wandered into their office asking for a matchbox to light a ganja-laced beedi.

Several surveys have found shockingly high rates of experimentation among young school-going children. One government study indicated that over 37% of 10th graders and 23% of 8th graders in Kerala have tried an illegal drug or inhalant at least once. Cannabis is among the first choices. The local media has dubbed the epidemic “Udta Kerala”, taking inspiration from the movie Udta Punjab that depicted the rapidly increasing drug problem in the northern state.

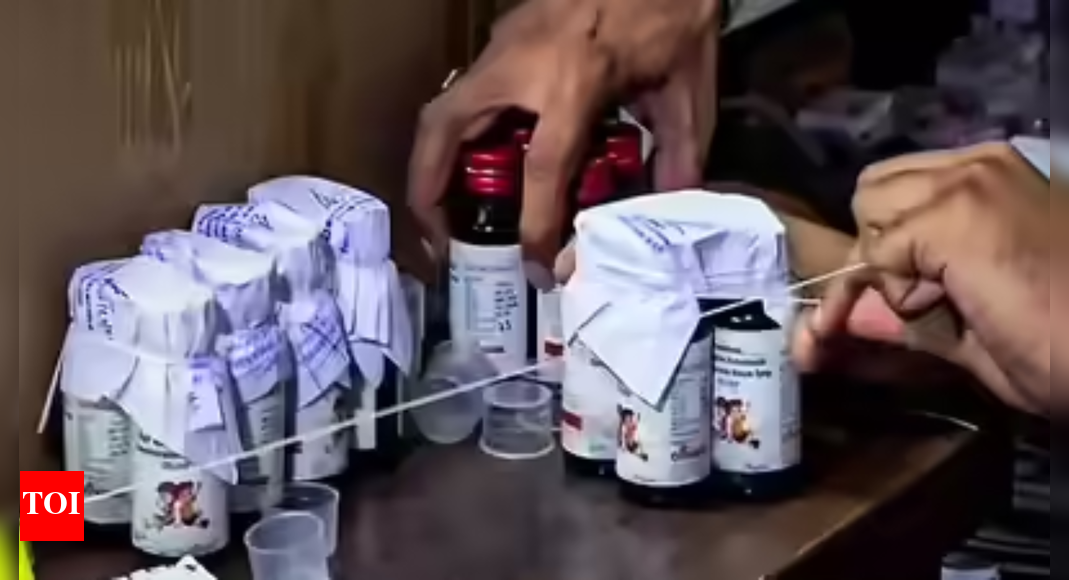

While drug addiction among Keralites begins with cannabis in most cases, it is still widely available. According to law enforcement agencies in the state, high-strength “hydroponic” cannabis with THC >40% has flooded Kerala’s market, making the 420 culture even more potent. This hybrid ganja does not grow in fields but in labs. It is often smuggled in from Southwest Asia. In fact, the smuggling of this type of ganja was essentially nil in 2022, but in 2024–25 alone, authorities seized over 89 kg from airports. In just seven months of 2025, the seizure rose to 129.7 kg.

Notably, Thai-grown hydroponic cannabis is highly potent and can fetch as high as Rs 1 crore per kg in the international market. Interestingly, because there is high scrutiny by law enforcement agencies to stop cannabis from entering India, smugglers have reportedly shifted to Middle Eastern routes. The 420 culture may romanticise ganja, but today’s reality is a booming international trade in ultra-strong cannabis, ensnaring Kerala’s youth in a cycle of addiction.

Why Kerala? Root causes of the drug menace

The drug problem in Kerala did not appear overnight. There are multiple interlocking factors that have made the state deeply vulnerable. Geography is a double-edged sword. Kerala has a 590 km long coastline that opens onto the Arabian Sea. It facilitates global trade but also provides an inviting gateway for narcotics.

Traffickers have exploited the international shipping lanes close to Kerala’s shores with increasing audacity. The state’s proximity to other transit hubs, including Bengaluru and Chennai, has created overland supply chains of contraband.

Let’s discuss some examples. Bengaluru is the nearest metropolis from where MDMA, also known as ecstasy, and methamphetamines are supplied to Kerala. Cannabis comes from the hills of Andhra Pradesh and Odisha via Tamil Nadu. The problem is so deeply rooted that police have mapped around 1,300 drug-peddling “black spots” across Kerala, covering neighbourhoods in city and rural regions alike.

Another problem is internet usage in the state. Drug cartels leverage this, and dealers operate through encrypted messaging apps and the dark web to accept payments in cryptocurrency, making it even harder for law enforcement agencies to track deals and bust networks.

Some media outlets have even claimed that, just like ordering pizza, one can order drugs in Kerala and get them delivered in just 15 minutes. On the ground, networks of bike-riding delivery agents ferry drugs to customers’ doorsteps. Using superbikes with fake number plates, some peddlers even pose as young couples to avoid suspicion.

The e-commerce-like drug trade has become a serious problem for law enforcement agencies as they must keep evolving their investigative techniques to keep up with the drug peddlers.

Beyond these supply-side factors, social and cultural dynamics within Kerala have contributed to a fertile market for drugs. A glamorisation of gangsterism and hyper-macho “cool” in popular media has influenced some young people to emulate gang culture. Drug cartels have identified this phenomenon. Local goons and organised gangs lure and groom students, treating them as protégés. These students then become low-level peddlers, further expanding the drug network while minimising risk for the kingpin.

According to excise officers, traffickers deliberately recruit school and college students as dealers precisely because juveniles attract less police suspicion. In one recent bust at a Kochi polytechnic, police found multiple students selling ganja on campus. First-time offenders were spared charges, but the incident laid bare how deeply drug networks have penetrated student communities.

Lack of job opportunities in the state is another problem. Thousands of young graduates with dreams that exceed available opportunities grow frustrated as they remain idle without any source of income. The vacuum created by joblessness gets filled by drug addiction, and in many cases, they become peddlers themselves.

Furthermore, Kerala is also known for migrant workers who choose to go abroad, mostly to Gulf countries, to earn a better livelihood. Children often stay back. The absence of parents creates an emotional void. The guidance that parents can provide cannot be expected from guardians taking care of the children. Such vulnerable teenagers often get pushed towards substance abuse as a form of escape or rebellion.

The drug problem is not limited to those who live in Kerala but also to those who have returned after doing work abroad. For example, at a de-addiction centre in North Kerala, a 28-year-old returnee from Abu Dhabi described how fellow Keralites overseas introduced him to “kallu” (crystal meth). His story mirrors the new trend of expatriate links in Kerala’s drug chain, where exposure abroad and easy digital access fuel cross-border addiction patterns.

Expanding smuggling routes and international networks

Intelligence agencies note that 95% of India’s narcotics trade is controlled by the Pakistan-linked D-Company (Dawood Ibrahim syndicate), which traditionally funneled drugs into north India. Since 2024, the state has scaled up its anti-drug operations. Under Operation D-Hunt, specialised squads conducted surprise checks. Reportedly, between 22nd February and 1st March 2025, they inspected 17,256 suspects, registered 2,762 NDPS cases and arrested 2,854 people.

In that particular week, law enforcement agencies seized 1.3 kg MDMA, 153.5 kg cannabis, and small quantities of heroin and hash oil. Then, on 11th September 2025, a statewide sweep led to 146 arrests and 140 new cases. MDMA and ganja were recovered. High-profile actions included an August 2024 MDMA lab in Hyderabad fronted as a pharma unit, and a September 2024 arrest of a Kerala native running ganja farms in Odisha.

However, the arrest patterns remain skewed. NCRB data show that in 2022, about 93.7% of NDPS arrests in Kerala were for possession for personal use. Of roughly 26,600 arrests, about 1,660 were peddlers, while about 24,959 involved small-quantity consumers. Networks often split stock below “commercial quantity” thresholds (for example, under 0.5 g MDMA, under 1 kg ganja), making possession bailable and complicating deterrence. Police report using follow-up searches to aggregate quantities and have argued for revisiting small-quantity definitions.

There is some discretion when it comes to juvenile and first-time users. For example, in a 2023 Kochi hostel case, several students were caught with small amounts of drugs. They were monitored by law enforcement agencies rather than being charged. Reported conviction rates are high, with thousands of NDPS convictions annually. However, most arrests still target users and low-level sellers.

Notably, communities and religious groups have come forward to help curb the situation. De-addiction services report more than a lakh outpatients and thousands of inpatients treated, which is a good sign. However, that does not mean the drug problem in the state is coming under control.

From crisis to collective action – The way forward

There is no doubt that Kerala’s drug problem needs a broad, coordinated approach and not just policing alone. In fact, both experts and policymakers agree with this. The central objective of programmes to tackle the drug problem should revolve around prevention and awareness. As schools and colleges have become prime targets of drug peddlers, it is essential to have structured drug education and peer-led programmes to help students stay away from the problem.

Furthermore, social media can play a vital role in educating youth against drugs. Reportedly, teachers and parents are being trained in the state to spot early signs of addiction, which helps in controlling substance abuse at the initial stage. There are also proposals for random drug testing in schools. Though such proposals are controversial, they indicate concerns over the reach of drugs into campuses.

The enforcement strategies focus on major supply chains and synthetic drugs like MDMA and methamphetamine. However, there is only one Coast Guard vessel currently patrolling the long Kerala coastline. The state is investing in scanners, drones and cyber surveillance to track smuggling and darknet transactions. Projects such as a WhatsApp-based citizen tip line, Project Yodhav, have yielded some leads, though the scale of trafficking remains largely unchecked.

The concerning aspect is that rehabilitation capacity is limited in the state despite rising demand. Government centres and NGO partnerships have reportedly treated 1.47 lakh people, yet mental health support and vocational reintegration remain patchy. Unless preventive education and social interventions expand faster than arrests, the “drug-free Kerala” goal will remain aspirational rather than achievable.