From Nehru’s intelligence blind spots to Indira Gandhi’s CIA-linked meddling: Read Congress’ history of selling national interests for personal gains

On Wednesday, February 11, Lok Sabha Leader of Opposition Rahul Gandhi launched a scathing attack against the Modi government over the India–US trade deal. But as has been the case with him, it was rich in drama but poor in credibility. Accusing the Centre of “selling Bharat Mata” and “compromising national interests,” Gandhi has once again chosen theatrical outrage over substantive argument, leaning on insinuation rather than evidence. His speech in Parliament mixed sweeping claims with emotive slogans, but offered little by way of concrete proof that India’s interests have, in fact, been bartered away. Gandhi argued that the government itself admits the world is entering a turbulent phase, marked by the decline of a unipolar order, rising geopolitical conflict, and the weaponisation of energy and finance, yet is allegedly allowing the United States to dictate India’s energy and financial choices. He went on to claim that if America says India cannot buy oil from a particular country, then India’s energy security is being “dictated externally.” From this premise, he leapt to the conclusion that the government has “sold” the country. This is a serious charge. It is also one made without any documentary evidence, without citing the actual text of the trade framework, and without explaining which specific clauses amount to a surrender of sovereignty. Instead, Gandhi relied on insinuations of “pressure,” spoke of “fear in the Prime Minister’s eyes,” and even dragged in references to the sealed “Epstein files”, a claim that has no demonstrable connection to India’s trade negotiations. This is not scrutiny; it is political theatre. He further claimed that tariffs have jumped from an average of around 3% to 18% and that US imports into India could rise from $46 billion to $146 billion, portraying this as an “absurd” one-sided concession. But trade negotiations are not conducted in slogans. Tariff lines, quotas, minimum import prices, and safeguard clauses matter, and without placing the full set of negotiated terms on the table, Gandhi’s numbers function more as scare figures than as a serious economic critique. More importantly, for the Congress party to posture as the guardian of national interest is an exercise in historical amnesia. Nehru was against building capacity in India’s intelligence infrastructure in China As historian Paul M. McGarr documents in his 2024 book Spying in South Asia: Britain, the United States, and India’s Secret Cold War, the Congress leadership itself has a long and uncomfortable record of decisions that weakened India’s strategic autonomy. McGarr notes that Jawaharlal Nehru actively resisted building a robust, geographically diffused intelligence infrastructure, particularly with respect to China. Nehru argued that expanding intelligence capabilities in a closed society like China was beyond India’s capacity and not worth the effort. This reluctance to invest in strategic capacity proved disastrous when China went to war with India in 1962, brutally exposing the costs of moral posturing combined with strategic neglect. Excerpt from McGarr’s book That was not merely an error of judgment; it was a structural failure of statecraft, one that left India blind at a critical moment in its history. McGarr’s work is even more damaging for the Congress when it turns to the era of Indira Gandhi. Citing Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s 1978 memoir ‘A Dangerous Place’, McGarr records that the CIA intervened in Indian politics at least twice, funnelling money to the ruling Congress party to prevent the election of communist governments in Kerala and West Bengal. In one instance, according to Moynihan, CIA funds were passed directly to Indira Gandhi in her capacity as Congress party president. Tashkent Agreement: Lahore and Sialkot could have been India’s, but Congress gave it away That habit of converting battlefield advantage into negotiating-table surrender did not begin or end with the Cold War intrigues described by Paul McGarr. It had already been institutionalised by the Congress party in 1966 with the Tashkent Agreement, one of the most consequential strategic blunders in independent India’s history. On 10 January 1966, after India had decisively outperformed Pakistan in the 1965 war, the Congress government agreed to return all territories captured by the Indian Army, including strategic gains in the Lahore sector and the vital Haji Pir Pass in Kashmir. These were not symbolic pieces of land; they were hard-won positions secured with blood and sacrifice. Indian troops had reached the Ichhogil Canal, Lahore’s last defensive barrier, and had seized Haji Pir, the key infiltration route into Kashmir. Militarily and diplomatically, India was in a position of strength. Yet, under international pressure and guided by a Congress foreign policy reflex that prioritised “process” over power, New Delhi chose to hand back its leverage and restore the status

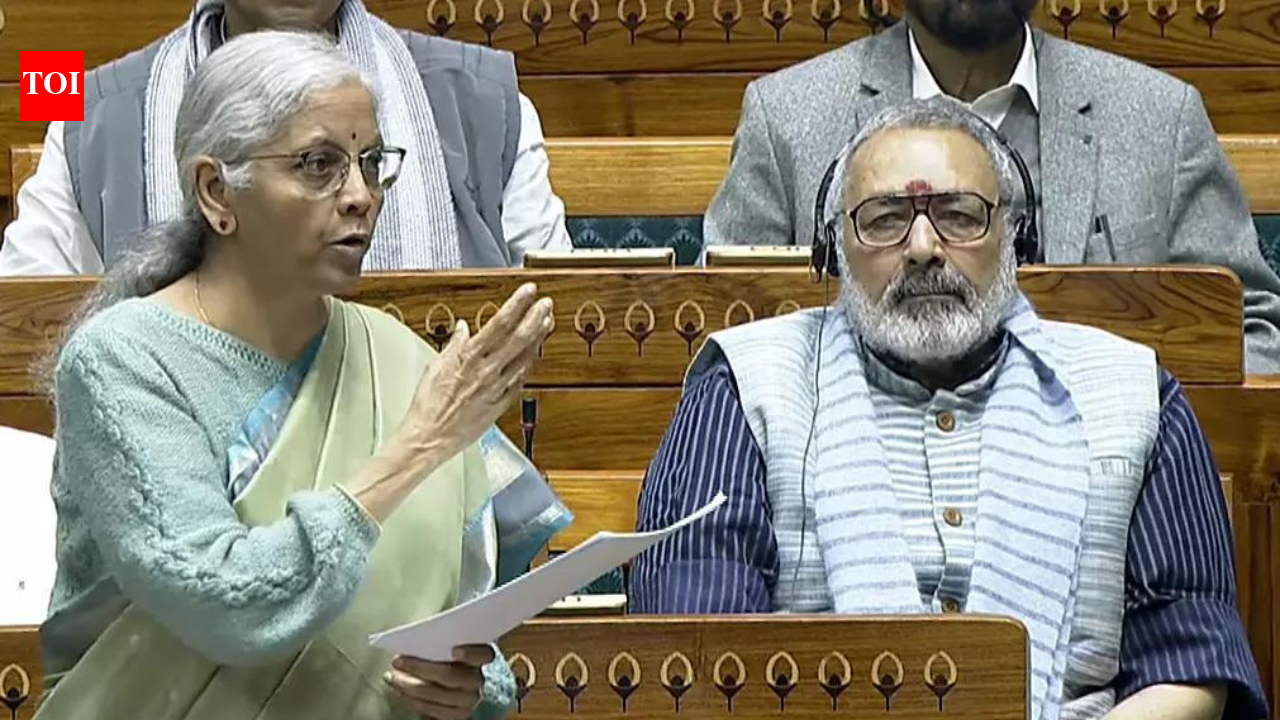

On Wednesday, February 11, Lok Sabha Leader of Opposition Rahul Gandhi launched a scathing attack against the Modi government over the India–US trade deal. But as has been the case with him, it was rich in drama but poor in credibility.

Accusing the Centre of “selling Bharat Mata” and “compromising national interests,” Gandhi has once again chosen theatrical outrage over substantive argument, leaning on insinuation rather than evidence. His speech in Parliament mixed sweeping claims with emotive slogans, but offered little by way of concrete proof that India’s interests have, in fact, been bartered away.

Gandhi argued that the government itself admits the world is entering a turbulent phase, marked by the decline of a unipolar order, rising geopolitical conflict, and the weaponisation of energy and finance, yet is allegedly allowing the United States to dictate India’s energy and financial choices. He went on to claim that if America says India cannot buy oil from a particular country, then India’s energy security is being “dictated externally.” From this premise, he leapt to the conclusion that the government has “sold” the country.

This is a serious charge. It is also one made without any documentary evidence, without citing the actual text of the trade framework, and without explaining which specific clauses amount to a surrender of sovereignty. Instead, Gandhi relied on insinuations of “pressure,” spoke of “fear in the Prime Minister’s eyes,” and even dragged in references to the sealed “Epstein files”, a claim that has no demonstrable connection to India’s trade negotiations. This is not scrutiny; it is political theatre.

He further claimed that tariffs have jumped from an average of around 3% to 18% and that US imports into India could rise from $46 billion to $146 billion, portraying this as an “absurd” one-sided concession. But trade negotiations are not conducted in slogans. Tariff lines, quotas, minimum import prices, and safeguard clauses matter, and without placing the full set of negotiated terms on the table, Gandhi’s numbers function more as scare figures than as a serious economic critique.

More importantly, for the Congress party to posture as the guardian of national interest is an exercise in historical amnesia.

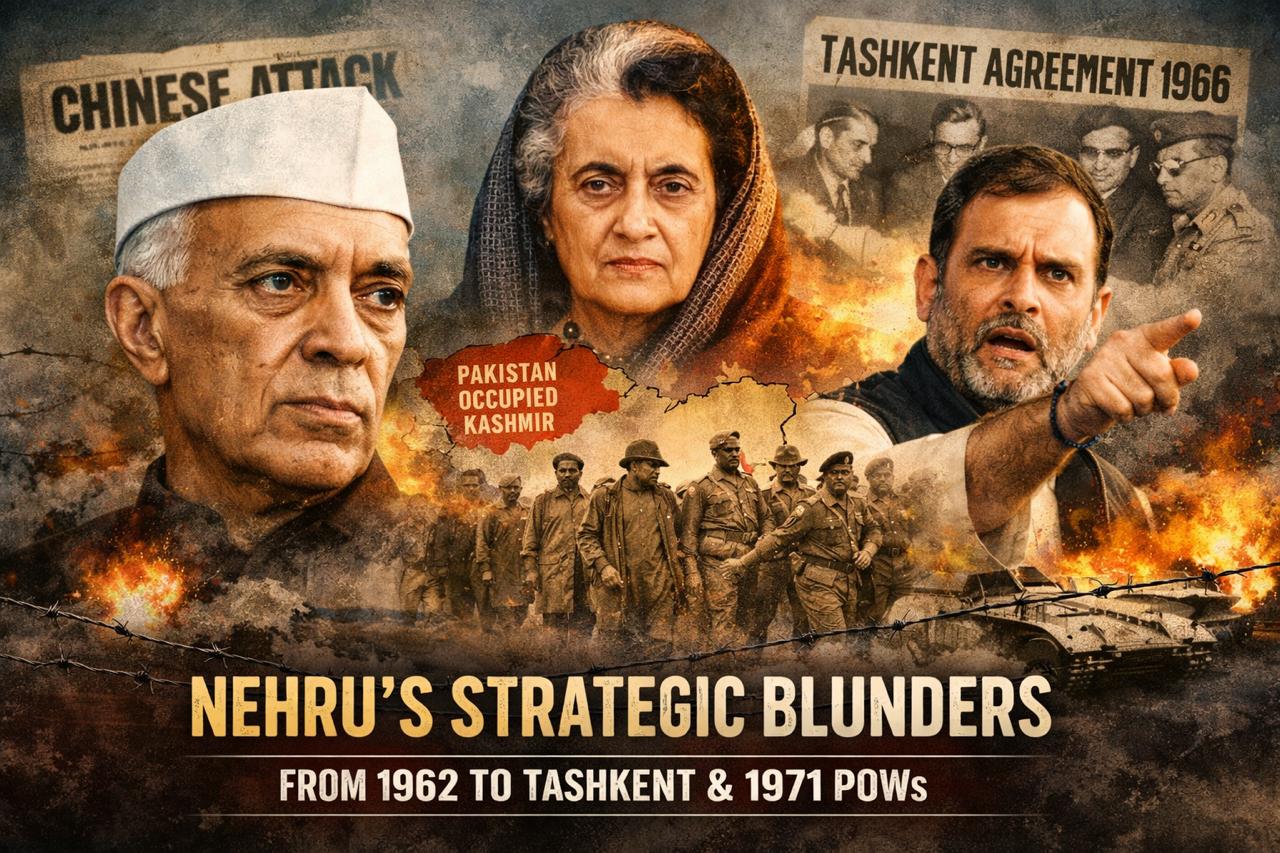

Nehru was against building capacity in India’s intelligence infrastructure in China

As historian Paul M. McGarr documents in his 2024 book Spying in South Asia: Britain, the United States, and India’s Secret Cold War, the Congress leadership itself has a long and uncomfortable record of decisions that weakened India’s strategic autonomy. McGarr notes that Jawaharlal Nehru actively resisted building a robust, geographically diffused intelligence infrastructure, particularly with respect to China. Nehru argued that expanding intelligence capabilities in a closed society like China was beyond India’s capacity and not worth the effort. This reluctance to invest in strategic capacity proved disastrous when China went to war with India in 1962, brutally exposing the costs of moral posturing combined with strategic neglect.

That was not merely an error of judgment; it was a structural failure of statecraft, one that left India blind at a critical moment in its history.

McGarr’s work is even more damaging for the Congress when it turns to the era of Indira Gandhi. Citing Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s 1978 memoir ‘A Dangerous Place’, McGarr records that the CIA intervened in Indian politics at least twice, funnelling money to the ruling Congress party to prevent the election of communist governments in Kerala and West Bengal. In one instance, according to Moynihan, CIA funds were passed directly to Indira Gandhi in her capacity as Congress party president.

Tashkent Agreement: Lahore and Sialkot could have been India’s, but Congress gave it away

That habit of converting battlefield advantage into negotiating-table surrender did not begin or end with the Cold War intrigues described by Paul McGarr. It had already been institutionalised by the Congress party in 1966 with the Tashkent Agreement, one of the most consequential strategic blunders in independent India’s history.

On 10 January 1966, after India had decisively outperformed Pakistan in the 1965 war, the Congress government agreed to return all territories captured by the Indian Army, including strategic gains in the Lahore sector and the vital Haji Pir Pass in Kashmir. These were not symbolic pieces of land; they were hard-won positions secured with blood and sacrifice. Indian troops had reached the Ichhogil Canal, Lahore’s last defensive barrier, and had seized Haji Pir, the key infiltration route into Kashmir.

Militarily and diplomatically, India was in a position of strength. Yet, under international pressure and guided by a Congress foreign policy reflex that prioritised “process” over power, New Delhi chose to hand back its leverage and restore the status quo ante, as if the war had never been won.

The consequences of that decision still haunt India. By returning Haji Pir Pass, the Congress government reopened the very routes that Pakistan would later use to push infiltrators and terrorists into Kashmir, laying the groundwork for decades of insurgency, bloodshed, and attacks that culminated in horrors like Pulwama.

The Tashkent Agreement did not buy lasting peace; it bought Pakistan time, legitimacy, and strategic breathing space despite its defeat. Ayub Khan returned home with nothing lost, while India returned home having converted victory into moral posturing. This was not statesmanship; it was strategic self-harm. When Rahul Gandhi today accuses others of “selling India,” he is speaking for a party whose own record includes giving away battlefield gains at Tashkent and, earlier, internationalising Kashmir in 1948, decisions that weakened India’s hand for generations. Against that backdrop, Congress’s sudden discovery of nationalist outrage over a trade negotiation sounds less like principle and more like historical denial.

Blunder of returning 93,000 PoWs to Pakistan: Throwing away India’s strongest bargaining chip

The pattern repeated itself even more starkly after India’s greatest military victory: the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War. Under Indira Gandhi, India not only broke Pakistan in two and created Bangladesh, it also took 93,000 Pakistani prisoners of war, one of the largest surrenders since the Second World War. This was an extraordinary strategic asset. New Delhi had in its custody the bulk of Pakistan’s eastern army, its officers, and its command structure.

At that moment, India held overwhelming leverage to press Islamabad on its most critical outstanding disputes, foremost among them Pakistan’s illegal occupation of parts of Jammu and Kashmir, and to secure the return of 54 Indian soldiers and airmen who had been captured by Pakistan and were officially listed as “Missing in Action” since 1971.

Yet, in a move that defies strategic logic, the Indira Gandhi government rushed to return all 93,000 Pakistani POWs under the Shimla Agreement without first securing the repatriation of those 54 Indian servicemen nor extracting a binding settlement on Pakistan-occupied Kashmir. Decades later, the fate of those Indian soldiers remains unresolved.

Evidence has repeatedly surfaced over the years, reports in international and Pakistani media, eyewitness accounts, references in books such as Bhutto: Trial and Execution, and testimonies from former prisoners, that at least some of these Indian POWs were held in Pakistani jails like Kot Lakhpat in Lahore. Even Benazir Bhutto admitted in 1989 that Indian POWs were in Pakistani custody, a claim later walked back by Pervez Musharraf. But diplomatically, India had already thrown away its strongest bargaining chip.

If Rahul Gandhi is serious about talking of “selling the nation,” he might want to begin by explaining why a foreign intelligence agency was allegedly financing his party to shape India’s domestic political outcomes. That looks far closer to a textbook case of compromising national sovereignty than negotiating a trade framework between two sovereign states.

One could even argue, using Rahul Gandhi’s own favourite phrase, that this was the real “vote chori”: external money being used to tilt India’s democratic outcomes in favour of the ruling Congress. Yet, on this record, there is no apology, no introspection, only selective outrage aimed at the present government.

There is a deeper irony here. Rahul Gandhi claims that India today is being “choked” by external pressure. But the historical record shows that it was under Congress governments that India’s strategic capacities were underbuilt, its intelligence apparatus constrained, and, if McGarr and Moynihan are to be believed, its ruling party even entangled with foreign intelligence funding for partisan political ends.

None of this means that the current government’s trade negotiations should be beyond scrutiny. They should not be. Any agreement with the United States must be judged clause by clause, sector by sector, and interest by interest. But scrutiny requires facts, documents, and arguments, not insinuations about “fear in the eyes” or unrelated references to international scandals.

Rahul Gandhi’s speech was heavy on rhetoric and light on evidence. Coming from a party with such a chequered record on strategic autonomy and national security, the moral grandstanding rings especially hollow. Before accusing others of “selling India,” the Congress would do well to answer uncomfortable questions about its own past, questions that history, and now serious scholarship, refuses to let disappear.