Before petroleum, there was bird poop: Read when Spain fought a war in South America, and US brought a law to claim islands. When empires went batsh*t crazy

On January 3, the US made a daring, overt attack on Venezuela after years of covert CIA attempts to change regimes. The operation, code-named Absolute Resolve, saw elite Delta Force commandos, over 150 aircraft, and airstrikes that culminated in the kidnapping of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro and his wife off to USA. Even though the Trump administration has been repeating ad nauseam that their problem with Maduro, and Venezuela is narco terrorism, pretty much everyone in the world knows that it was about oil, Venezuela’s vast oil reserves and US companies profiting from it. Global oil reserves A lot of wars in recent decades have been about oil. However, there was a time when wars were fought over other resources. Since the global discussion has shifted to South America for now, there was a period in history when South American nations fought a war with another Western power, not for petroleum, but for bird droppings. If you think the American attitude, which led to its fixation on Venezuela, is a recent development, history begs to differ. The USA, like other colonial and imperial powers, has long had a peculiar habit of being a maniac when it comes to resources. With no moral compass guiding the USA in these cases of brute realpolitik, one should not be surprised to learn that the USA once had the same passionate interest, not in gold or silver, but in heaps of bird poop. In fact, it treated batsh*t as a matter of ‘strategic national interest’. When bird poop was coveted This interesting episode of history unfolds in mid-19th-century America. Farming was rapidly being scaled. American farmers had moved beyond subsistence cycles. Commercialized Agriculture, dependent on markets and profit, was everywhere. Plantations still employed slaves, exploiting the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Industrialization of Agriculture was still decades away, as was a deeper, more scientific understanding of it. In this commercialised, market-driven agriculture, a worrying trend emerged. With every harvest, the production declined. By 1850, four-fifths of American farms were losing fertility. It was as if their greed was costing the farmers the fertility of their soil. The logic of empires is both inexorable and straightforward: profits must keep rising. But for ever-increasing profits, one needs more and more resources, some of which may lie beyond their geographical bounds. This Scarcity transforms those substances into strategic assets. A substance most people today would avoid stepping near became the centre of attraction in the mid-19th century. Something that spoils balconies regularly in this era became a globally coveted item. It became the object of international law, naval deployments, and outright wars. That substance was guano, the dried excrement of seabirds and bats, powdered for their intended use in farmlands. It was sourced from hot, dry islands without human habitation, mainly in the Middle Americas and the Pacific. The solution to the problem brought by market forces and commercialisation was ironically available in the same market for American farmers. Guano: The world’s most unlikely miracle material Guano may not sound like an ingredient for an empire, but in its day, it was coveted. Rich in nitrogen, phosphate, and potassium, it was a miraculous fertiliser that could turn poor, exhausted soil into highly productive farmland. It was an organic product rich in the three compounds, which are still the three main constituents of NPK-based fertilisers. It did wonders for farms. In a few cases, the harvest increased manifold. At a time when agriculture was critical to economies, and gunpowder relied on nitrates (mainly potassium), guano became a vital strategic resource for its two-pronged benefits. Colonial powers, hungry for productivity and military advantage, clamoured for access to it. Nevertheless, guano deposits were rare and geographically scattered: small, remote islands covered in layers of accumulated seabird droppings over centuries, maybe millennia. These islands could gather these deposits only because they were inaccessible to all for millennia. These layers of guano, one atop the other, solidified, and thousands of such layers formed massive guano rocks on these islands. Another contributing factor to their potency was the tropical dry climate, which prevented frequent rainfall and, in turn, helped preserve guano’s water-soluble nutrients. To modern eyes, the idea that nations would go to war over bird poop seems laughable, but to 19th-century strategists, it was nothing short of essential. Islands covered with centuries of bird poop The rocks no one wanted, until everyone did Islands off the Peruvian coast had the perfect conditions for producing high-quality guano. These favourable conditions made the Peruvian guano the most sought-after, as it was the most nutrient-dense. Colonial powers wanted this gold mine among the guano islands. Amo

On January 3, the US made a daring, overt attack on Venezuela after years of covert CIA attempts to change regimes. The operation, code-named Absolute Resolve, saw elite Delta Force commandos, over 150 aircraft, and airstrikes that culminated in the kidnapping of Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro and his wife off to USA.

Even though the Trump administration has been repeating ad nauseam that their problem with Maduro, and Venezuela is narco terrorism, pretty much everyone in the world knows that it was about oil, Venezuela’s vast oil reserves and US companies profiting from it.

A lot of wars in recent decades have been about oil. However, there was a time when wars were fought over other resources. Since the global discussion has shifted to South America for now, there was a period in history when South American nations fought a war with another Western power, not for petroleum, but for bird droppings.

If you think the American attitude, which led to its fixation on Venezuela, is a recent development, history begs to differ. The USA, like other colonial and imperial powers, has long had a peculiar habit of being a maniac when it comes to resources. With no moral compass guiding the USA in these cases of brute realpolitik, one should not be surprised to learn that the USA once had the same passionate interest, not in gold or silver, but in heaps of bird poop. In fact, it treated batsh*t as a matter of ‘strategic national interest’.

When bird poop was coveted

This interesting episode of history unfolds in mid-19th-century America. Farming was rapidly being scaled. American farmers had moved beyond subsistence cycles. Commercialized Agriculture, dependent on markets and profit, was everywhere. Plantations still employed slaves, exploiting the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Industrialization of Agriculture was still decades away, as was a deeper, more scientific understanding of it.

In this commercialised, market-driven agriculture, a worrying trend emerged. With every harvest, the production declined. By 1850, four-fifths of American farms were losing fertility. It was as if their greed was costing the farmers the fertility of their soil. The logic of empires is both inexorable and straightforward: profits must keep rising. But for ever-increasing profits, one needs more and more resources, some of which may lie beyond their geographical bounds. This Scarcity transforms those substances into strategic assets.

A substance most people today would avoid stepping near became the centre of attraction in the mid-19th century. Something that spoils balconies regularly in this era became a globally coveted item. It became the object of international law, naval deployments, and outright wars. That substance was guano, the dried excrement of seabirds and bats, powdered for their intended use in farmlands. It was sourced from hot, dry islands without human habitation, mainly in the Middle Americas and the Pacific. The solution to the problem brought by market forces and commercialisation was ironically available in the same market for American farmers.

Guano: The world’s most unlikely miracle material

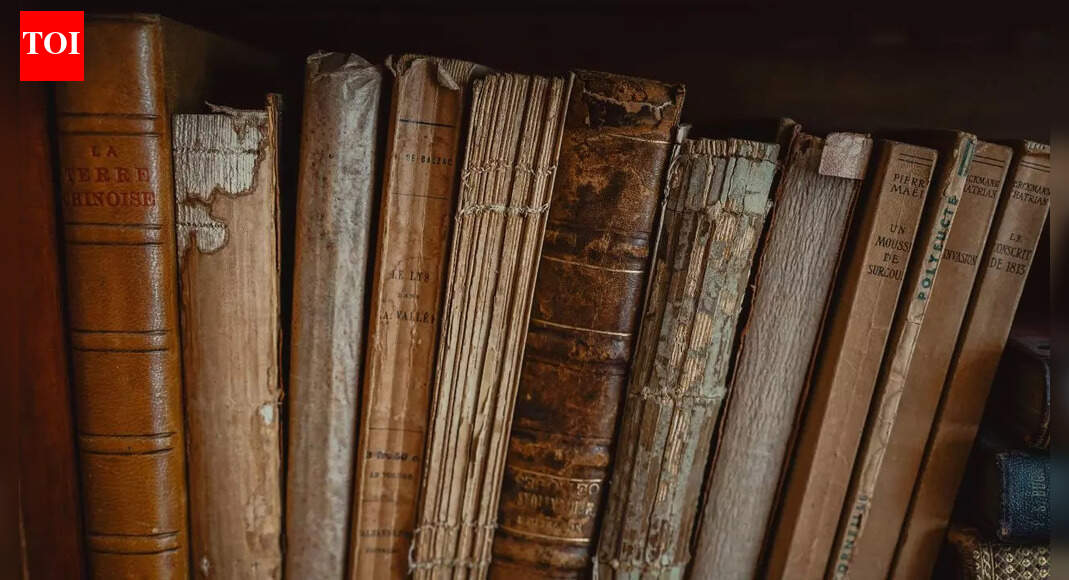

Guano may not sound like an ingredient for an empire, but in its day, it was coveted. Rich in nitrogen, phosphate, and potassium, it was a miraculous fertiliser that could turn poor, exhausted soil into highly productive farmland. It was an organic product rich in the three compounds, which are still the three main constituents of NPK-based fertilisers. It did wonders for farms. In a few cases, the harvest increased manifold. At a time when agriculture was critical to economies, and gunpowder relied on nitrates (mainly potassium), guano became a vital strategic resource for its two-pronged benefits.

Colonial powers, hungry for productivity and military advantage, clamoured for access to it. Nevertheless, guano deposits were rare and geographically scattered: small, remote islands covered in layers of accumulated seabird droppings over centuries, maybe millennia. These islands could gather these deposits only because they were inaccessible to all for millennia. These layers of guano, one atop the other, solidified, and thousands of such layers formed massive guano rocks on these islands. Another contributing factor to their potency was the tropical dry climate, which prevented frequent rainfall and, in turn, helped preserve guano’s water-soluble nutrients.

To modern eyes, the idea that nations would go to war over bird poop seems laughable, but to 19th-century strategists, it was nothing short of essential.

The rocks no one wanted, until everyone did

Islands off the Peruvian coast had the perfect conditions for producing high-quality guano. These favourable conditions made the Peruvian guano the most sought-after, as it was the most nutrient-dense. Colonial powers wanted this gold mine among the guano islands. Among the most famous guano sites were the Chincha Islands, off the coast of Peru. Barren, windswept, and devoid of inhabitants, these rocky outcrops seemed useless at first glance. But these conditions enabled it to contain vast quantities of the highest-quality guano, enough to secure agricultural productivity for years and thus the revenue that made empires jealous.

Spain, whose imperial grip on the Americas had been slipping since the early 19th century, saw an opportunity in Chincha Island. On April 14, 1864, they claimed the islands and began to extract guano, intending to bolster their finances. Peru and neighbouring states, equally aware of the value of these deposits, were not about to let Spain take them without contest. The combined forces of Peru, Chile, Ecuador, and Bolivia forced the Spanish to withdraw from Chincha Island. The stage was set for conflict, over rocks covered in bird excrement.

Peru, backed by Chile and Bolivia in this war, resisted. Naval battles erupted in the Pacific, cannons roared, and diplomats scrambled. The absurdity is almost too perfect to believe: fleets of ships exchanged fire over islands whose claim to fame was accumulated and solidified layers of bird droppings. Yet for those involved, the stakes were serious. Guano sales funded armies, sustained trade, and could determine national solvency.

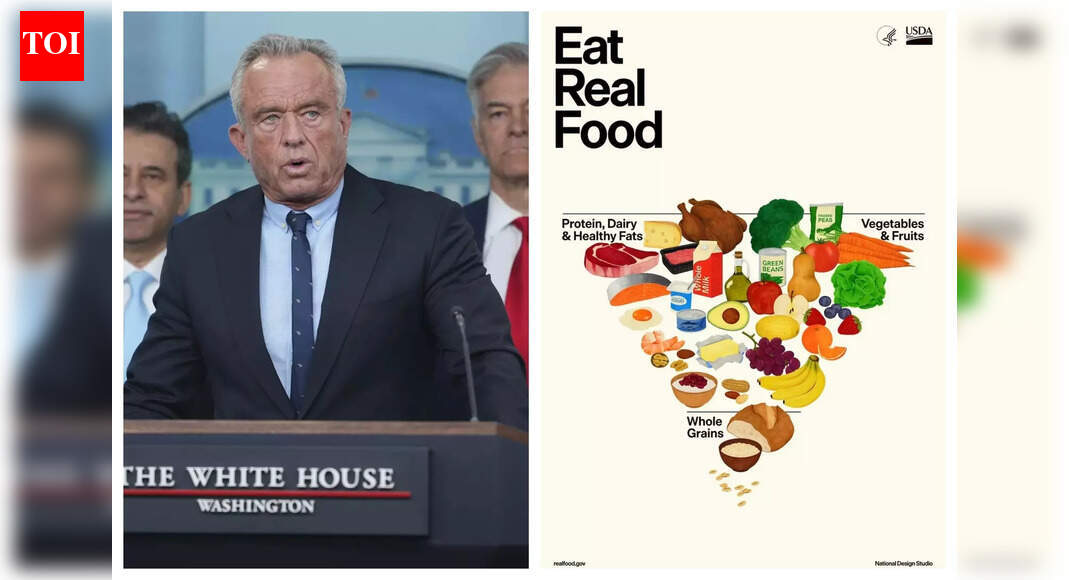

USA smells the poop of opportunity

North of the battlefields, the United States had already done something years ago. The US Congress passed the Guano Islands Act of 1856, a law (in force to this day) that seems whimsical today but made perfect sense to American lawmakers at the time. It allowed any American citizen to claim an uninhabited guano-rich island on behalf of the United States. American citizens went on sea voyages to spot guano and make it part of American territory. In 1857, the USA sent a 22-gun warship to collect and assess guano from islands that this law had just claimed. Dozens of islands in the Caribbean and the Pacific were claimed this way. American flags were planted, and resources were extracted from those islands. Settlements were rarely permanent; the goal was simple: ship the guano home, profit, repeat. The american approach was pragmatically casual: if an island had guano, it was America’s business. Under the Guano Islands Act, the US reportedly claimed more than a hundred islands. However, most of the guano islands were abandoned after the exhaustion of guano.

As abruptly as it rose, guano’s strategic relevance faded. Scientific advances revealed the workings of Guano. They knew the reason for guano’s success in boosting harvest. The production of synthetic fertilisers supplied nitrogen and phosphorus at scale. No longer was it necessary to risk warships, diplomacy, or cannon fire for a few tons of bird droppings. At first, it was replaced by bone meal, ground rock phosphate, etc., and with the advent of Haber’s process (1910s), urea became the norm.

For historians, the lesson is fascinating: a resource that once justified wars and laws became obsolete within decades. Entire empires adjusted, pivoted, and moved on, leaving abandoned islands behind, still covered in white, chalky layers, a monument to the quirks of history.

To keep perspective, consider this brief timeline of the guano era. Europe started seeing soil exhaustion around the 1840s. From 1840s to 60s, the Peruvian guano rocks were stripped at scale. The US brought the Guano Islands Act in 1956. The Chincha Islands war between the Spanish Empire and its former colonies was fought between 1864 66. In the late 1800s, the world started ignoring the bird droppings and moved on to synthetic fertilisers.