High inflation, low investments, rise in poverty and more: How Bangladesh is suffering from a never-before-seen economic crisis under Muhammad Yunus

Bangladesh is passing through one of the toughest periods in recent history. Energy shortages, a weak financial sector, high interest rates, and stubbornly high inflation join forces to bring the country’s economic activity down. Ordinary people work under the pressure of low wage growth, coupled with falling purchasing power, and businesses struggle hard to survive in an atmosphere that can be described as uncertain. However, the situation worsened after the interim took charge last year on 8th August. The highest inflation in South Asia One of the most visible problems for people in Bangladesh is inflation. Even after months of monetary tightening by the new central bank governor, inflation is still above 8%, making it the highest in South Asia. In October, inflation stood at 8.17%, according to the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. That is well above India’s 0.25%, Sri Lanka’s 2.1%, Nepal’s 1.47%, and even Pakistan’s 6.2%. Only Bhutan and the Maldives show slightly higher figures than Pakistan, but all remain far below Bangladesh. That means the cost of food, fuel, rent, and essential services keeps rising for ordinary households. People in this country have been saying that their lives have not become easier, even though the political situation has changed. The long economic pain, starting with the COVID-19 pandemic, never went away. For five straight years, Bangladesh has lived with high inflation and very slow wage growth. As a result, real incomes have fallen sharply, and poverty has gone up again. Private surveys estimate the current poverty rate at around 28%, although government data places it at 18.7% in 2022. Many families who were earlier considered “just above” the poverty line are now slipping back into poverty because their earnings can no longer keep up with rising prices. This growing gap between income and expenses has created widespread frustration. A steep drop in investment Another major concern is the steep drop in investment. Bangladesh has not seen such a low level of investment activity in many years. Even though inflation is high and interest rates have increased, experts say that investment in Bangladesh has never been extremely sensitive to interest rates alone. Instead, businesses point to issues such as frequent power cuts, corruption, extortion, bureaucratic delays, poor law and order, and constant changes in the exchange rate. But the biggest reason entrepreneurs give for not investing is instability. After months of violent protests, political uncertainty still hangs over the country. Many businesses do not feel confident enough to inject fresh capital or start new projects. Without restoring trust between the government and the private sector, economists warn that the investment slump will continue, keeping the economy stagnant. Government borrowing adds to the pressure. When the interim government took charge, government borrowing was rising at 11.61% year-on-year. Today it has more than doubled to 27.22%. At the same time, private sector credit growth has fallen to just 6.29%, the lowest in more than two decades. This means banks are lending more to the government and far less to businesses. A large share of government funds is spent on salaries, subsidies, and administrative costs, while development spending has sharply declined. In the first four months of the current fiscal year, only 8.33% of the Annual Development Programme was implemented. Rural areas are suffering because development work is slow, and new job opportunities are not being created. Non-Performing Loans: A financial sector under strain On top of these problems, Bangladesh’s banking system is facing its own crisis. The country now has the highest non-performing loan (NPL) rate in all of Asia. The Asian Development Bank reported last year that Bangladesh’s NPL rate in 2023 was 9%. But after the interim government exposed previously hidden NPLs, the figure has shot up drastically to more than 28%. Globally, Bangladesh is now among the worst performers in banking health, surpassed only by a few troubled economies such as Equatorial Guinea, San Marino, Ukraine, and Chad. This makes borrowing more difficult and expensive for businesses and weakens public confidence in banks. The Awami League government left behind a banking sector weighed down by bad loans, weak governance, political interference, and large-scale loan defaults. The interim government has tried to fix the situation. A special committee was formed to restructure the NPLs of 280 institutions, and the central bank issued new circulars based on these recommendations. But several state-owned banks are reportedly ignoring the guidelines. There are also allegations that some groups are still profiting from the crisis instead of helping resolve it. Merging weak banks with stronger ones has been suggested, but this is easier said than done. Governance reforms require political will, transparency, and strong l

Bangladesh is passing through one of the toughest periods in recent history. Energy shortages, a weak financial sector, high interest rates, and stubbornly high inflation join forces to bring the country’s economic activity down. Ordinary people work under the pressure of low wage growth, coupled with falling purchasing power, and businesses struggle hard to survive in an atmosphere that can be described as uncertain. However, the situation worsened after the interim took charge last year on 8th August.

The highest inflation in South Asia

One of the most visible problems for people in Bangladesh is inflation. Even after months of monetary tightening by the new central bank governor, inflation is still above 8%, making it the highest in South Asia. In October, inflation stood at 8.17%, according to the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. That is well above India’s 0.25%, Sri Lanka’s 2.1%, Nepal’s 1.47%, and even Pakistan’s 6.2%. Only Bhutan and the Maldives show slightly higher figures than Pakistan, but all remain far below Bangladesh.

That means the cost of food, fuel, rent, and essential services keeps rising for ordinary households. People in this country have been saying that their lives have not become easier, even though the political situation has changed. The long economic pain, starting with the COVID-19 pandemic, never went away. For five straight years, Bangladesh has lived with high inflation and very slow wage growth. As a result, real incomes have fallen sharply, and poverty has gone up again.

Private surveys estimate the current poverty rate at around 28%, although government data places it at 18.7% in 2022. Many families who were earlier considered “just above” the poverty line are now slipping back into poverty because their earnings can no longer keep up with rising prices. This growing gap between income and expenses has created widespread frustration.

A steep drop in investment

Another major concern is the steep drop in investment. Bangladesh has not seen such a low level of investment activity in many years. Even though inflation is high and interest rates have increased, experts say that investment in Bangladesh has never been extremely sensitive to interest rates alone. Instead, businesses point to issues such as frequent power cuts, corruption, extortion, bureaucratic delays, poor law and order, and constant changes in the exchange rate.

But the biggest reason entrepreneurs give for not investing is instability. After months of violent protests, political uncertainty still hangs over the country. Many businesses do not feel confident enough to inject fresh capital or start new projects. Without restoring trust between the government and the private sector, economists warn that the investment slump will continue, keeping the economy stagnant.

Government borrowing adds to the pressure. When the interim government took charge, government borrowing was rising at 11.61% year-on-year. Today it has more than doubled to 27.22%. At the same time, private sector credit growth has fallen to just 6.29%, the lowest in more than two decades. This means banks are lending more to the government and far less to businesses.

A large share of government funds is spent on salaries, subsidies, and administrative costs, while development spending has sharply declined. In the first four months of the current fiscal year, only 8.33% of the Annual Development Programme was implemented. Rural areas are suffering because development work is slow, and new job opportunities are not being created.

Non-Performing Loans: A financial sector under strain

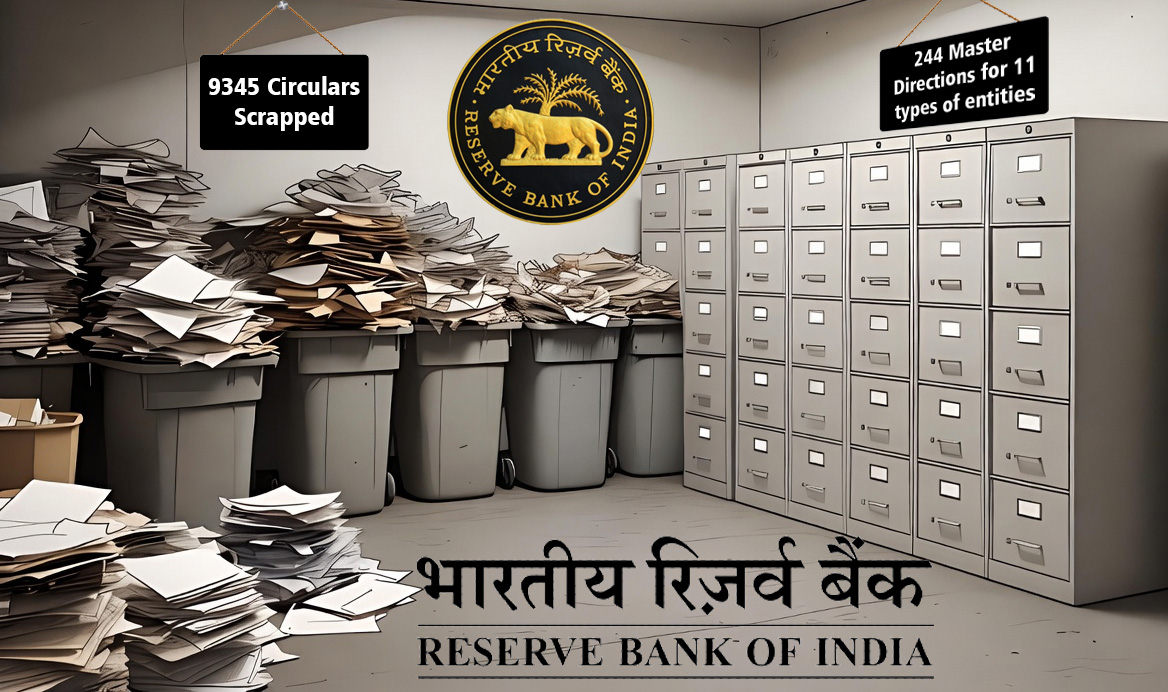

On top of these problems, Bangladesh’s banking system is facing its own crisis. The country now has the highest non-performing loan (NPL) rate in all of Asia. The Asian Development Bank reported last year that Bangladesh’s NPL rate in 2023 was 9%. But after the interim government exposed previously hidden NPLs, the figure has shot up drastically to more than 28%.

Globally, Bangladesh is now among the worst performers in banking health, surpassed only by a few troubled economies such as Equatorial Guinea, San Marino, Ukraine, and Chad. This makes borrowing more difficult and expensive for businesses and weakens public confidence in banks.

The Awami League government left behind a banking sector weighed down by bad loans, weak governance, political interference, and large-scale loan defaults. The interim government has tried to fix the situation. A special committee was formed to restructure the NPLs of 280 institutions, and the central bank issued new circulars based on these recommendations. But several state-owned banks are reportedly ignoring the guidelines. There are also allegations that some groups are still profiting from the crisis instead of helping resolve it.

Merging weak banks with stronger ones has been suggested, but this is easier said than done. Governance reforms require political will, transparency, and strong legal enforcement, things that will be challenging once the next elected government takes office.

ADB’s economic outlook: Slow growth, rising inflation

The Asian Development Outlook (ADO) April 2025 report by the Asian Development Bank paints a cautious picture of Bangladesh’s future. Bangladesh, the report said, is expected to witness a GDP growth of only 3.9% in FY2025 against the 4.2% growth it recorded in FY2024. Growth could improve to 5.1% in FY2026, but political stability and structural reforms will become decisive in that.

According to ADB, garment exports have continued to rise, but domestic demand is weak due to political transition, high inflation, industrial unrest, and natural disasters. Remittances may somewhat boost consumption and investment, yet overall demand will stay under pressure as fiscal and monetary policies are tightened.

Inflation, on the other hand, is expected to rise further, from 9.7% in FY2024 to 10.2% in FY2025. The reasons include limited competition in wholesale markets, poor market information, supply chain issues, and the weakening taka. High global tariffs, especially the new U.S. trade measures announced in April, could slow Bangladesh’s export growth in the coming years.

Asian Development Bank (ADB) also notes that service growth will stay slow due to reduced purchasing power and political uncertainty, while agriculture may suffer because of repeated floods. Manufacturing could improve slightly because of garment exports, but only if the global market remains stable.

Rising poverty in the post-crisis period

The World Bank released a report on Tuesday, 25th November, which has also raised red flags for the Nation’s poverty rate. Their latest projections show that Bangladesh’s poverty rate is climbing again after decades of improvement. According to the World Bank’s micro-simulation model, the poverty rate may cross 21% in 2025. The number of poor people is estimated at around 36 million.

Even more worrying is the large number of people living just above the poverty line, 62 million in 2022. These households are at high risk of slipping back into poverty because of inflation and reduced income. The period between 2022 and 2025 has been described by experts as a phase of “reversal,” meaning Bangladesh is undoing years of progress in poverty reduction.

Several analysts say this reversal is tied to a change in political priorities. Between 2016 and 2022, poverty reduction slowed as the government focused more on debt-driven mega-infrastructure projects while ignoring governance reforms and social investment. Corruption increased, political accountability weakened, and economic inequality widened.

The PPRC’s own poverty survey in 2025 estimated an even higher poverty rate, 27.93%. Taken together, these reports suggest the interim government has inherited a country where poverty is becoming more widespread and harder to manage.

Trump tariffs and their impact on Bangladeshi economy

Adding to the challenges is the new tariff regime announced by U.S. President Donald Trump. Bangladesh managed to negotiate the tariff on its garment exports down to 20%, a significant relief compared to the initially proposed 37%. This is crucial because Bangladesh is the world’s second-largest garment exporter, and the sector contributes more than 80% of total export earnings while employing about 4 million workers.

The reduced tariff brought Bangladesh in line with other major exporters such as Vietnam, Sri Lanka, and Indonesia. India, meanwhile, faces a higher 25% tariff after failing to reach a broader deal with Washington.

Bangladesh’s negotiators emphasised that they safeguarded the garment sector while also agreeing to purchase more U.S. agricultural products, an exchange designed to help their food security plans and build goodwill with American farming states.

Although the 20% tariff will still raise costs and reduce competitiveness slightly, industry leaders believe Bangladesh is better positioned than many of its rivals. But they also admit the sector is nervous, as long-term impacts could affect export earnings if global demand weakens or if other countries negotiate even better deals with the U.S.

Unrest, violence, and uncertainty after the Awami League’s fall

The economic crisis cannot be separated from Bangladesh’s political turmoil. The fall of the Awami League government in August 2024 created a long period of unrest. The country had already gone through waves of protests, strikes, and clashes, but things got drastically worse in July 2024.

Violent clashes between protesters and security forces paralysed the cities of Bangladesh for weeks on end. The roads were blocked, transport services were disrupted, and many factories remained closed. There was unrest in the countryside, too, with broken supply chains aggravating inflation and slowing down economic activity even further.

In these months, the collapse of governance hurt business confidence. Many investors pulled out or postponed projects. Foreign investors, too, put their plans on hold, waiting to see whether Bangladesh could stabilise politically. The interim government tried to calm the situation, but rebuilding confidence takes time, especially after such widespread violence.

How Sheikh Hasina was removed from power

The protests against government actions that eventually forced Hasina out of office started in July 2024, when people launched large-scale demonstrations against government actions. The situation quickly escalated into widespread violence. On 5th August 2024, after weeks of clashes that left hundreds dead, the military forced Hasina to leave the country.

The interim government took over and declared parliamentary elections for February 2025. But the Awami League says elections under the ban will not be free and fair. It claims thousands of its workers have been arrested across Bangladesh in the past year.

There is still no agreement on how many people were killed during last year’s uprising. A United Nations report released in February estimated that up to 1,400 people might have died. The interim government’s health adviser put the toll at more than 800, with nearly 14,000 injured. Hasina rejected both figures, calling for an independent international investigation into the deaths and injuries.

A nation struggling to find stability

There was a time when Bangladesh used to be recognized as a country that showed phenomenal economic growth, steady poverty reduction, and impressive human development. Today, violent unrest, political instability, and the rising influence of hardline Islamic groups have created deep uncertainty. The collapse of an elected government, along with widespread protests and military intervention shook the very foundations of democracy.

Simultaneously, the economy is fighting high inflation, weak investment, a failing banking sector, and increased poverty. New U.S. tariffs and global uncertainty add to the pressure.

Bangladesh now stands at a crucial crossroads. Whether it can overcome these economic and political crises will depend on restoring trust, strengthening governance, and ensuring a peaceful transition to an elected government. Only then can the country return to the path of stability and growth it once enjoyed.